Local History

ICE HARVESTING

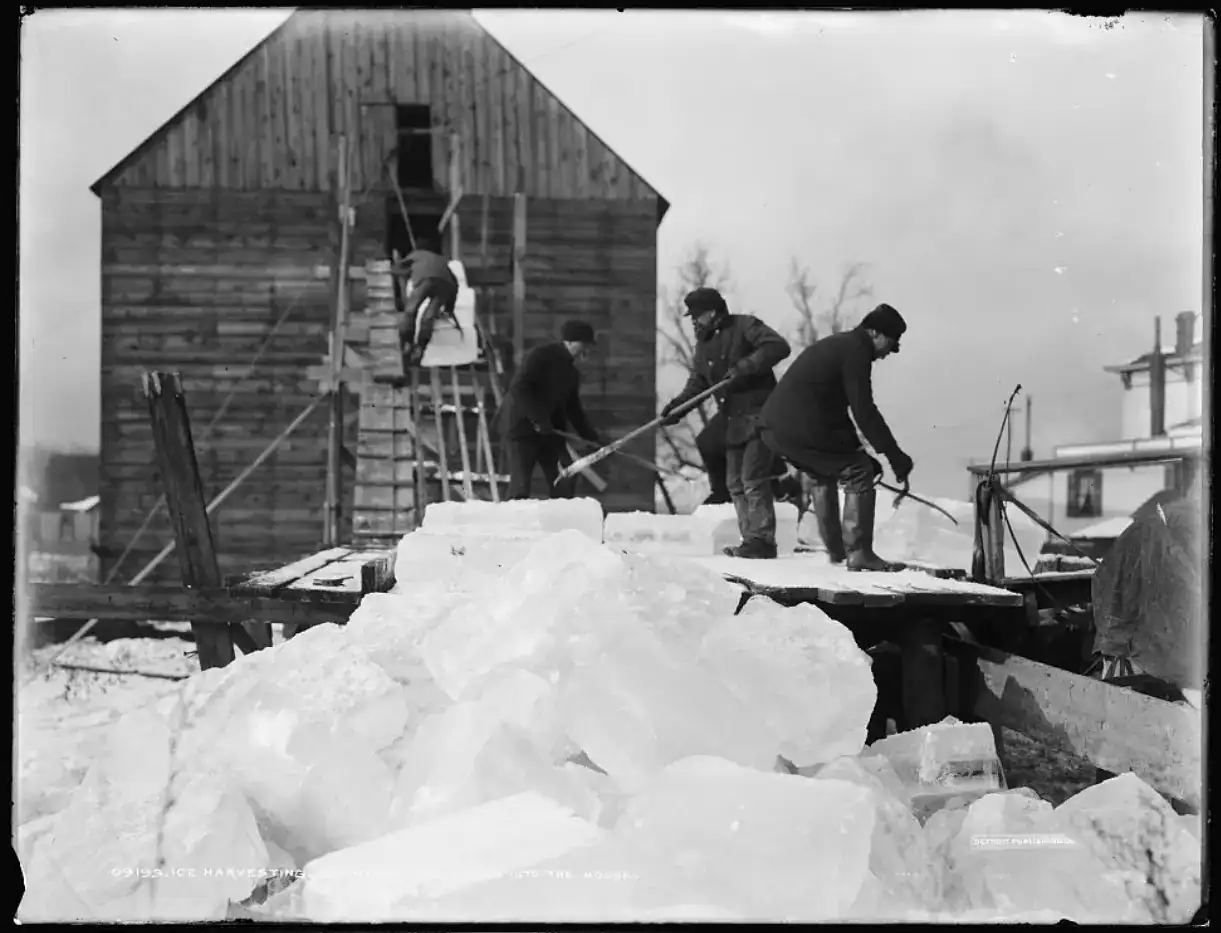

A profession for the feeble, most assuredly this was not. For all involved, commercial ice harvesting requires strength, a sturdy constitution, and keeping your wits about you. Top of mind: You don’t want to wind up in the drink and become an instant human popsicle.

“Ice harvesting was a job for a strong man, and no weakling needed to apply,” confirmed H.L. Van Deusen in a 1940 Kingston Daily Freeman column. “Men who were boys then were employed to ride the backs of the horses used in the ice harvesting. This was a cold job, and the boys would be so bundled up in warm clothing that they could not be recognized at a short distance, and when they dismounted from the horse’s back they would be so stiff they could hardly walk.”

Real winters and the ice box

Back in the day, as they say, the whole of New York State would transform into one big ice machine come the cold weather, which, I might add, was a more reliable occurrence in that era than it is these days, despite the “normal, old-time” winter we seem to be experiencing this year. Yet even in those days of more reliable – read cold and not only cold, but consistently cold – winters, it was hardly the surest of things. The heaviest days of ice harvesting would ordinarily occur in January and February.

Fortunately, modern refrigeration, a relatively new phenomenon, had the decency to come into existence. Two things, of course, had to happen first. One, for it to be invented and put into use, and two, that the rural electrification project be completed, accompanied by a radical shift in thinking in the pursuit of keeping things cool. Whereas ice involves the introduction of cold to facilitate the cooling process, modern refrigeration calls for the removal of heat.

The start of the ice harvesting industry

Let’s back up for a second. Writing in the Rhinebeck Gazette, Louise Tompkins noted, “Hamilton Pray of the Clove in the Town of Union Vale revolutionized ice harvesting in 1870, when he invented an ice plow. One plow was drawn across the ice by a single horse, cutting the ice through far enough to permit a man with an ice saw to saw through it quickly. An ice plow, drawn by two horses, could cut twice as much ice in the same amount of time. With this machine, Mr. Pray created an ice harvesting industry in Dutchess County, which employed 2,500 men during the season.”

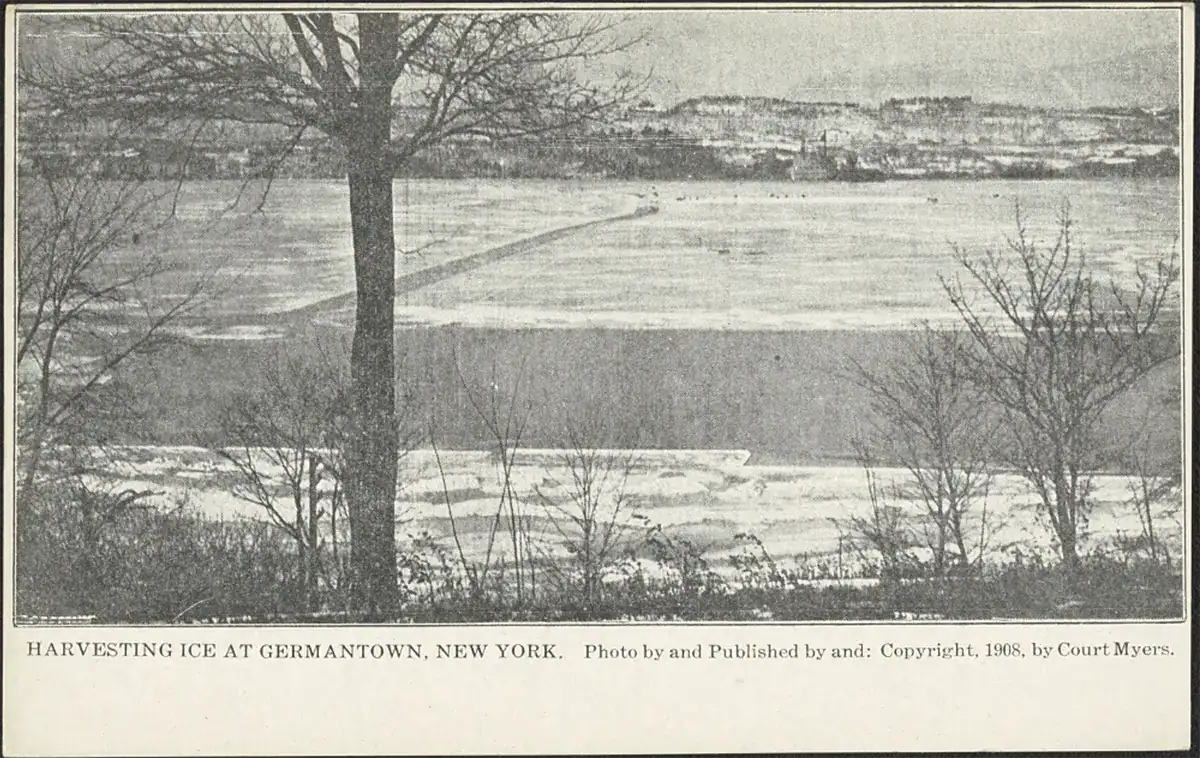

Added Tompkins, “An elderly man told me that he had worked with men harvesting ice on the Hudson River. He said the cakes on the river were usually 20 to 21 inches thick, which was thinner than the ice harvested on ponds because of the tide and currents in the river. The cakes of river ice were placed in large ice houses on the shore of the Hudson and packed in quantities of salted hay. In the warm weather, most of the ice was sent on boats to New York City, where there was a great need for it. He said he was paid $3.00 or $3.50 a day for harvesting ice.”

The Staats and Wilder ice

businesses in Chatham

Wouldn’t you know it, but there’s an ice harvesting business in my blood. In the Chatham area, two of the largest ice dealers were George Staats and Herbert Wilder, my great-uncle, who would go on to be killed in action in World War II on July 3, 1944, in the V-1 attack on Sloane Court, England. According to another uncle, on the site of my home, built by Uncle Herbert’s dad, there once stood an enormous pile of sawdust, a byproduct of the family’s adjacent sawmill operation and handy to have around at ice storage time.

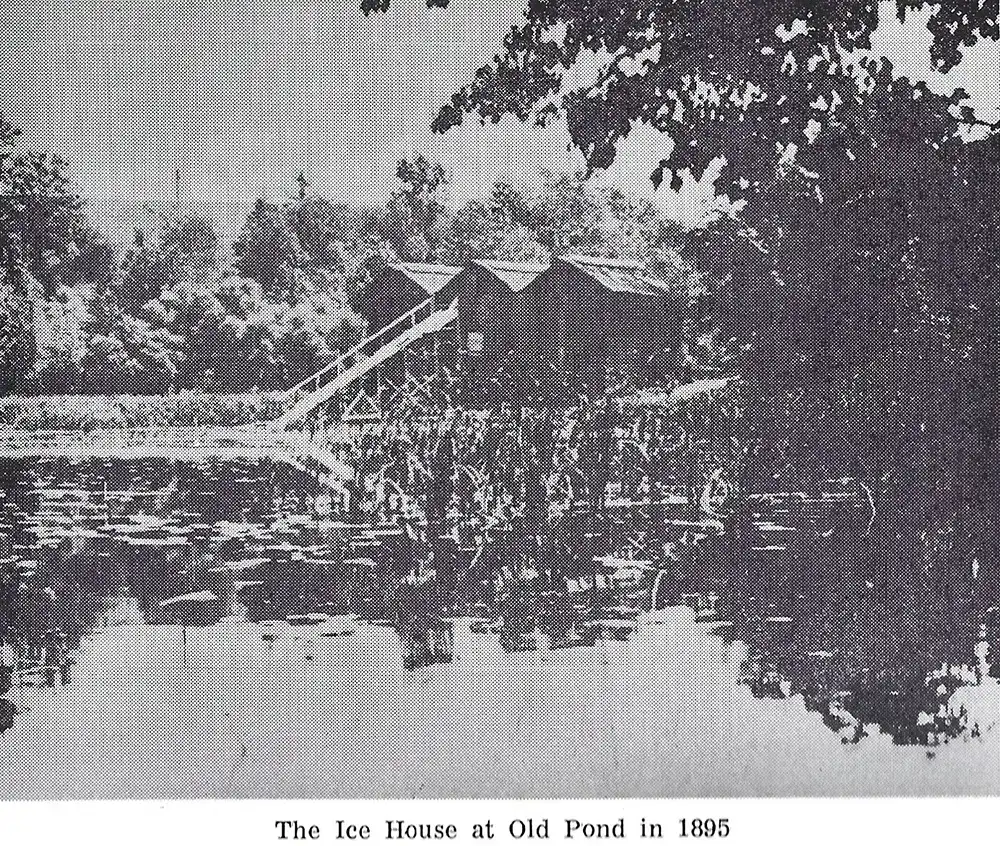

Staats Pond (now known as Sutherland Pond, centerpiece of the Ooms Conservation Area) on Rock City Road in Chatham was home to Staats’ ice house, from which they would deliver ice all around Chatham. (Another personal aside: My grandfather, Don Wilder and Herbert’s brother, would announce we were off to visit “Staaty,” and off we’d go in his ancient green Ford pickup, up to Rock City Road to visit George, who seemed equally ancient, although just about everyone over the age of 10 seems ancient when you’re seven.)

An undated Chatham Courier story relates that, come home delivery time, Staats would arrive at the “house with the block of ice to be placed in the great old oak-paneled ice box in the rear hall.” In that story, Donald Kerns of Ghent is quoted discussing the actual harvest: “Sometimes a horse would go in; sometimes we’d fall in. Everybody and everything got sunk one time or another, but we’d always get out, freezing to death, but we’d get back up on the ice.”

Quoting Dr. Frank Maxon as he recalls his childhood in Chatham observing ice harvesting at the Old Pond: “I always remember that in the area where the ice was taken out, the water refroze absolutely crystal clear, so clear in fact that you could see the pickerel swimming around in the pond!”

From a 1930 Chatham Courier story entitled “Ice Harvest Next Week to Employ Many”: “About 60 men will be given extra employment in the immediate vicinity of Chatham next week, when local ice dealers and the Borden plant start to harvest the winter supply of ice. Herbert Wilder, dealer, stated today that he planned to fill his house early next week, and George Staats of Rock City is filling his house this week, giving employment to approximately twenty-five more men. All of the dealers are rushing their tasks of getting the winter crop in as the ice, while of good quality, ranges from nine to ten inches in thickness on local ponds, and it has been their experience, they say, that the first crop of ice is always the best.”

In those days roughly 30 cakes of ice, with one cake running around 110 pounds, would be conveyed by horse and cart to the ice house, which was built with sawdust in the walls for insulation. Let’s keep in mind, pavement was not then a thing, the roads were oftentimes muddy and not easily passable even without several tons of ice aboard.

The particulars of ice harvesting

At the former East Chatham pond, I was once told, dealer John Weaver built a platform over the pond across from the now-East Chatham Fire Company firehouse on Frisbee Street, then cut the ice using horses and a plow. In time, a gentleman named Bill Eckert made a power saw out of a car motor. He used it to cut down around two inches from the bottom of the ice, hit it, and get it loose, where an existing channel moved it along. Once it was loose, men would deploy claws and hooks to get it into position for the horses to pull it up onto the platform. It would take two or three men, exhibiting great care and shod in steel-tipped shoes, to pull it up and load it.

It sounds relatively straightforward, all in all, with known hazards and the like, but no. As with any business endeavor, things are always capable of going haywire owing to circumstances that are neither controllable, well understood, nor foreseeable.

Case in point: Reported Troy’s The New York Press in 1909, under the headline “Ice Dealer Fights Water Pollution by Cement Co.,” members of the Independent Retail Ice Dealers’ Association were keenly interested in the fate of the lawsuit that Patrick Doherty, described as the owner of large ice houses in Jersey City and on the Hudson River, had lodged against the Catskill Cement Company.

“One of the charges made by the ice men is that a joker put into a bill regulating the cutting of harvest of ice in the Hudson River has practically deprived them of all chance to harvest ice profitably, because that joker permits the Catskill Cement Company, which is known among ice men as the Cement Trust, to pollute the waters of the Hudson.”

Doherty, who had been battling the “Ice Trust” for half a decade, owned a large ice-harvesting facility at Alsen, near Catskill, on the river. Along comes the cement company to “build an enormous plant adjoining that of Doherty, and is now planning to build four more plants further upstream. In Doherty’s complaint it is set forth that dense smoke, ashes, cinders, coal dust, clay dust, offensive gases and fumes, soot, and other deleterious matters come from the cement plant and settle on the river, polluting it.”

Consequently, alleged Doherty, the water is polluted before it turns to ice, yielding ice made “unhealthful, unwholesome, worthless, and unsalable.” No word on the ultimate disposition of that particular skirmish.

The changing tide

Wartime, as is its wont, brought with it hiccups of its own. As 1918 opened for business, out in Central New York, The Auburn Citizen would report, under the subhead “Many Horses Taken for War Use,” that “one difficulty which the ice harvesting companies on Cayuga Lake are now in direct contact with, is the problem of obtaining teams for filling houses that are located at points distant from the lake shore. … In years past the ice harvesting season saw a continuous string of horse-drawn wagons or sleighs from Bridgeport to Seneca Falls. Now there are but a few teams that can be secured for work.”

Horsemen were quoted to say that the few remaining horses “are now being used behind the battle lines in France.”

Ice harvesting as an industry continued along a relatively fruitful financial path until the early 1930s, when it began to peter out, leaving behind a rich legacy and scores of empty buildings once dedicated to helping keep things cool. •