Featured Artist

Art is a Life Force — Hilary Cooper

It was a warm afternoon when I had a wonderful conversation with Hilary Cooper, a portrait artist who works across multiple mediums – painting, watercolor, and clay. Drawing together likenesses of people, each of her subjects carries a unique narrative.

As we walked around some sculpted heads in progress, I watched how they seemed to converse with one another – quietly keeping an eye on each other as they emerged from Cooper’s hands. It is an intimate practice: looking closely, talking about life, and, through that exchange, finding a person’s smile, their gaze, their character – gathering threads and weaving them together.

Her work is filled with muted colors, impressionistic strokes, and expressive marks that allow the material itself to speak. There’s a quiet joy in preserving the image of a loved one – held forever on a wall, a constant presence in our thoughts.

You studied art, what first inspired you to pursue a career as a painter?

Mother and Children portrait, oil on linen, 2007.

I discovered early on that I had a knack for art. I was a foreign service brat – my father worked as a diplomat – so we lived all over the world. I especially remember our time in Karachi before we were evacuated from Pakistan to London.

Both my parents came from very modest backgrounds. My father was a Kansas farm boy, and my mother grew up in Brooklyn. Her parents were immigrants who came to the US from Greece. In her day, public high school education was excellent, and she went on to Barnard and later Oxford and London School of Economics. She always believed deeply in the value of education. So, when we landed in London, I began attending a local school in North London, in St. Johns’s Wood.

My mother was unimpressed with the school I was attending – it was dreadful – and she tried to persuade the embassy to move us to a better school district. When they wouldn’t, she opted to send me to a boarding school, which I absolutely loved.

Living in London during the school breaks and having access to all that art on our doorstep was amazing. I was constantly at the National Portrait Gallery, fascinated by faces. Later, I also studied at Goldsmiths College for a semester.

As a foreign service kid, you’re always watching people – trying to read them, make friends quickly, adapt. You become attuned to faces, to expressions. I think that made me deeply curious about how an artist captures a likeness. That curiosity drew me into portraiture. It turned out I had a real feel for it, and I knew from early on that I wanted to be a portrait painter. That said, I was a bit hopeless in traditional art classes – coming up with something from scratch didn’t come easily to me. But I was good at rendering what I saw. That’s where I found my strength.

We didn’t have much money, so when I graduated from college, I felt a real sense of financial insecurity. I kept asking myself: What kind of job could I take that would allow me to support my artistic pursuits? Where could I live that would make that possible?

Kim and Prisca Marvin in progress still in clay, 2025.

New York was the only place that made sense; it felt, to me, like the only truly non-provincial town in America at the time. I had a choice: I could wait tables, or, on the advice of a friend, I began interviewing at banks and eventually became a banker. I went through the credit-training program at NatWest USA and NCNB National Bank of North Carolina, which would become Bank of America. It was like getting paid to get an MBA. But during that time, I never let go of art. I studied at both National Academy and The Art Students League during evenings and weekends. I was a banker by day and an art student by night.

It wasn’t until I got married that I felt the security to study art full-time. That’s when I really started putting miles on a paintbrush and working regularly with models. In the mornings, I’d work in studios with indoor light; in the afternoons, I’d shift to those with north-facing windows, learning to observe how natural light moved across the figure.

Later, in my thirties, I began to sculpt. My Russian sculpture teacher, Leonid Lerman, told me bluntly, “Hilary, you know nothing. You are only copying!” And he was right. He also taught me structural anatomy, adding: “In youth, structure is concealed beautifully. In old age, structure is revealed beautifully.”

I loved his teaching – it was so deep and demanding. I took as many of his classes as I could. I had to create my own curriculum from scratch, which is why, even now, I sometimes feel inarticulate when I talk about my work.

I think that’s a familiar feeling. People develop their own language when they talk about their work. It’s important that you know what you’re saying, even if you don’t always say it in the way others expect. Writing down thoughts helps me process what I am working on.

Yes, Ann Truitt’s Daybook, her journal of being an artist and living her practice, is a great one to read. But honestly, the career aspect of being an artist didn’t occur to me. I really wish I’d had a mentor back then who said, “Get an MFA.”

At the time, my husband and I were living just outside Sag Harbor, back when it was a much simpler place. An artist friend, Louisa Chase, who taught at RISD and was part of the art world, once told me, “An MFA helps because it allows you to build a whole social world around your work – a community.”

Peonies, oil on canvas, 30×24, 2025.

Absolutely. It can give you a foundation to read more deeply and to write and think differently about your practice. But today there are also so many valuable online courses that can help shape that process instead of an MFA. Writing and thinking about your subject can be as revealing as the making itself.

It really can. As James Salter once said, “Nothing exists unless it’s written.” He was a dear friend of ours, he sat for me, and I made a bronze of him.

What was it about this area that prompted your move here?

Well, we were living in Sag Harbor and used to rent out our house every summer. I had just met Susan Rand. One day she called and said, “I would love you to do a show with me at the Norfolk Library; however, they only show people who live here, why don’t you come up and visit?”

So, we drove up, Chris complained the whole way, but once we got here, he loved it. We saw this house for sale, and that was it, we moved. In Sag Harbor, you have to lay rubber to get from a secondary road to a primary one; you can’t park anywhere or find a parking space. Up here, you can just pull right up to where you want to go. It’s so much easier.

Portrait in encaustic, 1995.

What motivates your art practice?

Art is a life force. It’s hope. It’s creative energy. I live for it. My work feels like my children. I thrive on that motivation, on the practice. The repetition, the variation – it feels vital. I especially love doing portraits. Physically, we’re all 99% the same, but it’s that small difference – that one thing – that makes someone utterly unique.

The painter Giorgio Morandi and the sculptor Marino Marini have both been strong influencers as well as Isamu Noguchi and Alice Neel. Also, the book The Artist’s Way, which I read when it first came out. I re-read it recently. It’s still so relevant. I’d forgotten how clearly it talks about “the crazy makers” in your life.

I learned a lot about art, philosophy, and sculpture from Leonid Lerman, a Russian artist and a true genius. He was the first art teacher I really admired and respected. I complained once that I wished he’d come into my life earlier to which he replied, “when the student is ready the teacher will come.”

Do you have a project you’re most proud of?

In 1996, I was staying with a client whose portrait I was about to begin. But on the very first morning, I fell down the stairs and suffered a spinal injury that left me a quadriplegic. I was given the slimmest chance – a shard of hope – that I might regain some movement. Miraculously, a couple of months later my toes began to wiggle and, after intense rehab, I walked out of the hospital on my own. I am incredibly fortunate.

Emerging from that extraordinary physical and emotional experience, as my mobility returned, I knew I wanted to paint a series of portraits of people with disabilities. When I was in a wheelchair, I became hyperaware of others in wheelchairs. It struck me how often people only see the chair and not the person.

I had an epiphany while painting a New York City policewoman in uniform. Again, realizing that the viewer’s attention was fixed on the uniform – it overwhelmed everything else. Appearances can blind us. So emerged my book titled Divided Portraits: Identity and Disability, which explored disability and how we perceive it. This shaped the format of the series: I created diptychs, two-part portraits, with one panel showing the person and the other showing the wheelchair separately. By removing the chair, I separated the subject from the uniform.

One of the portraits was of Jimmy Huega, the first American to win an Olympic downhill skiing medal. I played with scale in some works, shrinking the chair in relation to the figure. Other images were inspired by the visual strategies of artists like Bonnard. It felt essential to make this work – to talk about it, to give something back.

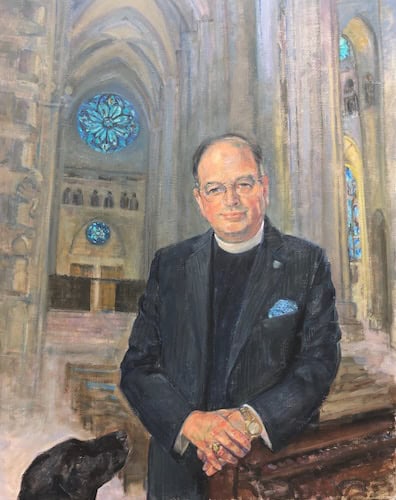

Dogs always work their way into Cooper’s paintings. Even the Dean of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine.

Leafing through the book now, it’s a stunning portrayal of people whose mobility has been impaired by illness or injury. Every person carries a profound narrative – each finding a new way to live. This book changes the way we see identity itself.

Are you ever nervous about working with clients?

Oh no, I’m never nervous. I’m excited to meet people. There’s always a conversation throughout the session, which gives me insight. However, one of the most memorable experiences was painting Peter Matthiessen, the writer and Zen Buddhist. I had been asking him to sit for me, and he kept saying, “I can’t sit still.” And I said, “Well, I know that you can.”

I’d been to a Zendo sitting, I knew he could sit for 45 minutes. So, I had him sit in his Roshi robes, and I couldn’t believe how much I achieved in that silent time without talking. It was incredibly productive.

What also fascinates me about portraiture is how abstraction drives the process – examining light, dark, tonality, and shape. You’re not thinking about the person directly. You’re focused on the formal elements, the abstract shapes that make up the figure. Their personality? That comes later. It emerges on its own. Sometimes, a preconception sneaks in. I remember painting a young woman whose portrait had been commissioned by her mother. To me, she strongly resembled her father. As I was working away, and just before we were about to break, I stopped and looked at the painting – and there on the canvas was … her mother! I was stunned. I had thought she resembled her father because she had his coloring, but through painting, something deeper came through.

That’s why it’s so important to clear your mind of preconceptions. I’m always excited by how, through the act of painting itself, the soul just … appears.

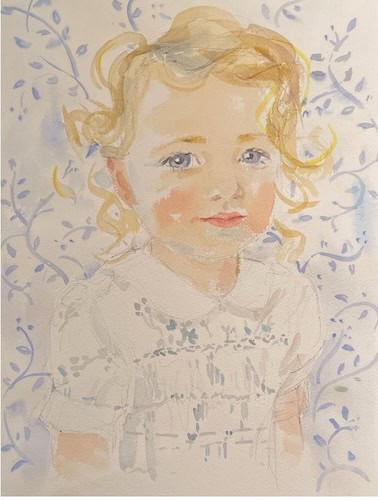

Watercolor portrait, 2025.

Can you talk about your sculptural approach to creating a portrait? Whether it’s a sculpture or a painting, do you use 360-degree images to capture detail, or do you sketch?

With sculpture, yes, you really must capture all those little nuances. It’s almost as if the form reveals itself just before it disappears. You must stay alert to this as it is seen from all angles. I tend to work fast. I paint quickly. But I make a conscious effort not to capture the likeness too soon. If I get the likeness right away, it can be constraining. It sort of stills the painting when it becomes fixed too early. So instead, I often begin with the background or the surroundings. I let the figure emerge more slowly, letting the painting breathe and unfold over time.

Have you taught or led workshops? What’s the best advice you would give a new artist?

Yes, I’ve taught at Anderson Ranch in Colorado. I’ve been teaching again this summer at the Scoville Library: Blooms and Brushwork, a two-day, watercolor, flower-painting workshop. Last fall I taught a pet portrait drawing class. My advice to new artists, treat it like a career. Too often, art is seen as a hobby, but if you’re working full-time at it, then it is your career. Own that.

You currently have a show on view at Sweet Williams Bakery. Can you talk about your flower portraits?

Those paintings began when I started house-swapping with a woman in Paris. She stayed in my New York apartment a few times, and I banked a few weeks with her, just enough to spend a month in Paris. So, I took my dog and my watercolors and went.

I had just started getting back into watercolors and bought this amazing bouquet. I began painting the flowers as if they were portraits. I imagined the vases as bodies, and the flowers as their heads, each with its own personality. Sourcing pots from antique shops and flea markets gave even more personality. I tend to paint them in a single sitting, trying to find the spirit of each flower, they really do become someone.

Watercolor is such a wonderful medium: it’s fast, expressive, and slightly unpredictable. It’s alive and immediate. It lends itself particularly to portraits of children, which occupy a great deal of my time these days, especially since the pandemic when I instituted FaceTime “sittings,” which is a pleasantry when dealing with three-year-olds! •

If you are in the Salisbury area, pop into Sweet Williams on Main Street to see Cooper’s flower portraits. They are a breath of fresh air. Cooper has worked on an enormous inventory of portraits. She is able to recognize our distinct traits and carry them onto a canvas, or into another form, where they continue to live and breathe. Some of her commissioned work includes James Salter, George Plimpton, Peter Matthiessen, Erica Jong, Ed Koch, Kimberly Rockefeller, John Roselli and Patricia Hearst Shaw, and she has been featured in numerous magazines. If you are interested in more of Cooper’s work, please contact her directly through her website, hilarycooper.com, Instagram @hilarycooperart, or by emailing her at hilcoop@gmail.com.