Featured Artist

A Pause in Time — Christina Dobbs

I caught up with Christina Dobbs on a cool summer morning in her studio in Lakeville, CT, for a chat about her painting practice. Dobbs’ work often originates from photographs and experiences she has witnessed, transporting the viewer back to that time and moment. The paintings depict landscapes blurred through gestural marks and washes, with built-up layers gradually giving depth and resonance to the surface. The viewer’s focus lands on the figures and their actions, inviting questions about the narrative unfolding within the scene.

Through this interplay of setting and gesture, the paintings emanate the tactile sensations of the moment, either the oppressive heat or biting cold equally to moments of pure joy. The viewer is fully immersed in that moment. Whilst there are hints of an idea, we don’t know what lies beyond the picture plane, nor what might happen in the next frame.

What does creating art mean to you?

Art for me is a way of expressing an emotion, a place in time. It’s a feeling you recognize, and it must come out as something from within oneself. The feeling takes form in a painting, a drawing, or whatever creative form you need to express something inside of you that needs to be expressed. The art I create is narrative, but not straightforward, because my work explores the fragility of life and everyday experiences. The change in life is the existence in these moments in time that are constantly shifting and changing. We’re not in control of pushing a button on a tape recorder to stop time. But in a way, painting is a method of doing that.

So, it’s going back to a particular moment in time and just being in that place?

Each work shows one moment when the temperature was a specific number, and the grass had a certain tone. You can recreate it, but it’s not about what’s happening – it’s more about figures in a landscape caught in a single instant.

I work from photographs, and the image must be compelling enough for me to see potential in it. I take the essence of what’s in that photograph that holds meaning for me; everything else is abstracted away. The figures in my work tend to be in their own world, reflecting the idea that we often don’t realize – especially when we are young – how quickly time passes and that we cannot rewind. That is the joy of childhood: living entirely in the now, unaware that the freedom of a particular age or moment will never come again. The figures feel vulnerable because they exist within a landscape, and when you view it, what’s there is not straightforward. The figure remains in its own world – just as we all do – because life is not within our control. It is unpredictable.

The Goldfinch is a significant book for me in this way, as it shows how a single moment in time can shift everything you have ever known.

Have you always painted?

I returned to painting later in life, though I have always been creative. It was only after moving to London that I truly had the opportunity to focus on it. Honestly, the weather was so bleak that I made a New Year’s resolution to take either a painting or writing class to get through the winter. I discovered Heatherley’s School of Fine Art and on a whim walked up to the receptionist after the semester had already begun. She told me, “It’s funny, someone just dropped out of Ian’s class. He’s teaching today. You could join.”

That moment proved transformative. Ian Rowlands became a pivotal figure and mentor for me. Until then, I had never painted formally with oils. Everything I learned in those early years came from him. His belief that materials are an essential part of artistic practice deeply shaped my own approach. I went on to take more and more of his classes – intense, full-day, atelier-style sessions that pushed me forward.

Eventually, Rowlands encouraged me to pursue an MA. Around the same time, a close painter friend was applying to graduate programs, and her excitement about the process made me realize I should do the same. On the very night of the deadline, I submitted my application to City & Guilds of London Art School. That program was a turning point in my development. It wasn’t simply about producing work; it was about articulating the deeper drive behind why I paint. In many ways, the MA felt like an intense form of psychotherapy, and I would not be where I am now without it.

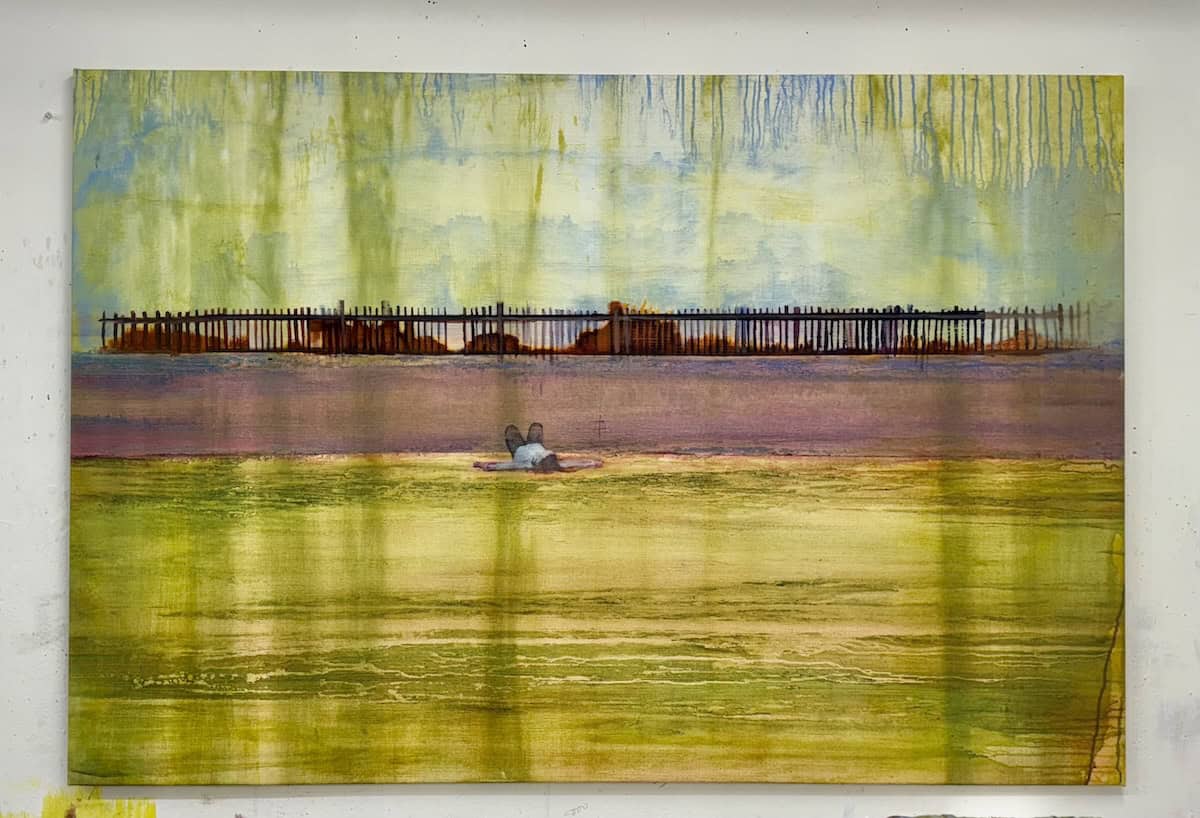

Acid Rain (cropped). 2022, oil and acrylic on linen 167.5 x 91 cm.

The MA taught me the language of art-making, which opened my practice and gave me the freedom to work in new ways. It also helped me expand a voice I hadn’t yet been able to articulate. Which leads me to ask: what motivates your practice?

For me, making work is like an itch that must be scratched. When I see the potential in a photograph, or when I witness a moment that prompts me to take one, I sense the possibility of creating something unusual. That spark is what excites me about life. When an image carries potential, I’ll explore it through many iterations, returning to it until I know I’ve fully resolved it. I work from current experiences, translating them into paintings that carry both memory and presence. For example, last year we dropped our youngest son off at college in Nashville, and I was heartbroken. Back in the studio, I turned to a photograph I had long wanted to paint: the back of him standing on a beach, the water in front of him, tossing a ball repeatedly into the air. I titled the piece Launched. In painting it, I felt I was with him again. I know him so well that the act of painting became a form of comfort, a way to stay close even as life moved forward.

Recently, while visiting my mother in South Carolina, I discovered a box of old family slides. Looking through slides takes effort, but the images were astonishing moments of myself as a child, captured in time. A photograph holds a memory in a way that can summon everything about that moment: the heat in the air, the atmosphere, the emotions.

One image was of my sister and me, and I remember it vividly. That summer was unusual, almost surreal. My mother was in the process of leaving my father, though we didn’t know it then. She was from North Carolina, and she drove us through the South – Georgia, the Carolinas, Virginia – trying, I think, to get us away from the familiar. It was sweltering, an inferno, and the trip felt like a fracture in my life. When my parents split up, I hadn’t seen it coming. That painting of my sister and I came out of that moment, holding both the memory and the rupture it contained.

You can feel the heat and hear the insects hum.

There were these old cotton mills, defunct and abandoned, set against the dry, red clay dirt and a constant haze. That atmosphere carried a deep sense of loneliness, which seeps into some of my work because that’s exactly what it felt like. The paintings I made from that time reflect the experience of being a child, without control, placed in environments that weren’t always joyful, which shapes both its mood and its narratives. These fractures come through in my work: moments in time that you don’t recognize as pivotal when you’re living them.

Those ruptures ultimately put you on your path. I wouldn’t be able to do what I do without the experiences I’ve had – no regrets. The way life has unfolded for me feels fortunate, because every shift and fracture has shaped who I am and the work I create. I believe our experiences evolve us into what we’re capable of doing. Very few artists haven’t endured some kind of rupture. It gives you resilience, and that resilience is essential.

I was one of the oldest people in my MA program, and I came to realize that my life experiences are the material I draw from in my work. They are what give it depth and substance. You reach a point where those experiences need to be expressed, and when you’re ready, the work pours out of you. I’ve often turned to writing as a way of understanding things. When I find myself in a confusing place, writing helps me uncover the reasons behind it. Painting serves the same purpose for me. It is a process of discovery and interpretation. What matters most is capturing the essence and mood within a photograph. From there, I work to translate that feeling into a painting, stripping away everything irrelevant so that only what is essential remains.

Have you ever made a commission for a stranger? As you didn’t have a clear sense of them, was it difficult?

It can be, but I learned from the first one. A client saw one of my works at a show in London and asked me to paint him and his wife walking together. She had been seriously ill and was now cancer-free, which he shared after I completed the initial piece. I approached the piece working from the photograph of them walking in a quiet, urban landscape and translating it into my own visual language. As he had seen my work, I assumed he appreciated my palette and style, so the shift in emotional tone he requested, required me to reinterpret the work while balancing my own artistic vision with his personal narrative.

I am now more aware of how important it is to communicate on a commission. You must really find out what it is they are anticipating and what they want.

What artists or writers have inspired you?

Gerhard Richter has been a significant influence. He also works with photographs and archives, which I do in my process. He will render something and then obliterate it. That’s part of what resonates with me.

Battleship. 2025, Gesso, sructura paste, acrylic and oil on archival board, 8 x 12 inches.

But the memory is still there, and it becomes a conversation in the work.

Exactly. You get these “ghosts” through the paint. His relationship with the material is so important. He lets the materials have a voice and take their course. We’re not in control of everything, and sometimes what you don’t control turns out to be brilliant. It’s a dialogue between oneself and the material, requiring a continual response from the artist.

Additionally, other artists I admire include Peter Doig and the Swedish artist Karen Mamma Anderson. Mattias Weischer, whose mentor was David Hockney, also fascinates me. His empty, hugely textural rooms make you wonder what’s happening inside, and you can clearly see Hockney’s influence. Noah Davis is another huge influence; I loved his show at the Barbican, and it’s exciting that his work is coming to Philadelphia. Hernan Bas captivates me as well, with his narratives of beautiful young people in this in-between space. You’re left questioning who they are and what they’re doing. I love Fairfield Porter for the clarity of his work. There’s nothing ambiguous about it. In writing, anything by Joan Didion is epic; she has this uncanny ability to capture both mood and a precise moment in time. Luc Tuymans and his new book are also remarkable.

If you could beg, borrow, or steal a piece of work from anywhere in the world, what would it be?

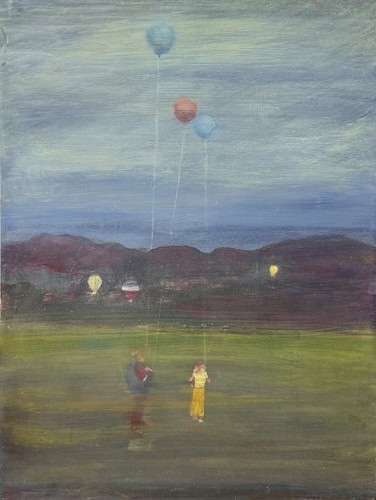

Launched. 2024, oil on grey board, 30x 21 cm.

Oh, I’m sure it would be a Richter. And I’d love to have dinner with him – just sit next to him, talk about the painting, and talk about everything.

What is your favorite time to create?

From the morning until about six o’clock at night. I am not a night person. When I’m tired, I get supercharged. I start rearranging furniture, shuffling papers, or cleaning the brushes.

What media do you generally work with?

I’m more entrenched in oil, but I’ll use some quality watered-down acrylics to distress the canvas and lock in certain areas where I want the sky horizon to be. Then I can abstract in those areas. When I have enough texture going on, I’ll go into oil.

How do you overcome a creative block if it ever happens?

Sometimes stepping away is useful. I usually work on multiple projects at once, so I don’t get too stuck on a single piece. You can dabble in different things, and if something isn’t working, it usually means there’s a reason – you just haven’t figured it out yet. Painting is all about problem solving. If you recognize there’s a problem in a piece but can’t identify it, you’re not ready to continue. Stepping away allows you to see it clearly. Until you know what the problem is, any attempt at a solution is just slapping paint on a surface, hoping to hit the mark by chance. That’s sloppy, and I would never do that. Sometimes you catch yourself mid-process and think, “wait a second, what am I doing? I’m just repeating.” That’s usually the point to pause and reassess.

It’s almost like a jigsaw puzzle. If you get stuck in one corner, you can move to another. When I’m unsure how to approach an image, I sometimes just paint over a ratty computer printout, sloppily working in oil to break it up. Little tricks like that help me move forward.

What brought you to this area?

My husband and I were living in New York before we had kids and were looking for an escape place outside New York City. The Hamptons felt too much like a scene. In October 1996, we came up for a weekend to stay with a friend. We went swimming, played tennis, and biked. I wanted to rent a house for the summer and see what it was like. This lake house was the last one in my long search. I was about to give up when Susan Rand called and said, “There’s one house I think you might like.”

Water is essential for me, so we rented it that day. Six weeks in, they decided to sell. Oliver was on a business trip in London, and I called him in the middle of the night: “They’re putting this house on the market. We should buy it. I know it sounds wild.” We ended up buying it, literally pulling all our savings together. That Christmas, we gave each other bathrobes. There was no extra money, but we had the house!

I love it, when you just instinctively know something is right; it’s the universe speaking. I’ve always believed that houses choose you. Do you have a project you’re most proud of or want to do, and how do you maintain focus on a long-term project?

I have pieces I’m proud of, and sometimes the process itself can be exhilarating – like the painting of the boys, which was pivotal for me and experimental. I work across large, medium, and small pieces simultaneously, approaching one painting at a time while keeping an overview of what I want. I created an entire series with kids in the garden, climbing on each other, playing football, and having fun. I made small works on paper and a couple of larger paintings; it’s a whole body of work in progress, where each piece speaks to the others. I’d love to have a show in Berlin, but solo shows are exhausting. You give everything, and it’s so exposing. I loved the mix of critique and positivity, but you also must plan for what comes after the show.

What was the best piece of advice you received regarding your practice, and what advice would you give an artist today?

Step away when you don’t know which direction to take. Pay attention to the warnings about overworking a piece; placing too much material without intention can ruin it. Don’t be a perfectionist. Experiment with materials like a child and allow the work to lead you; you might create something you didn’t intend. Most importantly, relax.

What shows and residencies do you have coming up?

I’m heading back to the UK this month for the John Moore exhibition, which features my work. I am excited to see it. A few years ago, I had a residency in Newfoundland during March. It was both raw and amazing. I had to wear crampons just to go outside! The studio was huge, with a bedroom and bathroom; it was a phenomenal experience. Sometimes I joined the communal dinner, but other times I worked all day in my pajamas. Adjusting to the quiet and being unable to go anywhere takes getting used to, but it allows you to become embedded in your work. I created two extraordinary pieces there, building rituals like lighting candles every morning. When I returned home, it felt like everyone was shouting. I’d become so used to the silence.

Now I treat every trip as a sort of residency. When I’m in my studio, I can’t stop painting; it’s like denying someone food. It’s a physical practice; I make a big mess, and it feels like being in a rocket ship, ready to fly. •

To learn more about Christina Dobbs, you can visit her website atchristinadobbs.com, on Instagram: dobbschristina, or email her at either cdobbs@me.com or info@christinadobbs.com.