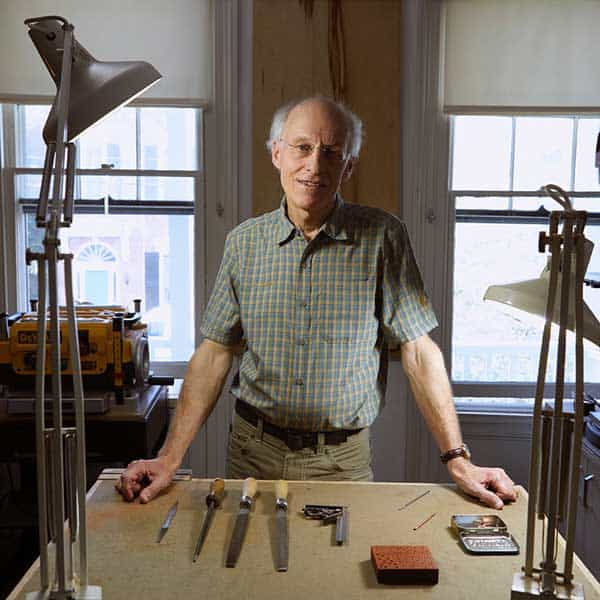

Featured Artist

Balance Amidst Uncertainty

“Throughout my life, the best things have happened because I took a risk, not a foolhardy risk, but one that was necessary or calculated. So although we might want a direct path, a clear destination, we must be careful not to be overly cautious.” – Steven Careau

The word that the artist Steven Careau most often uses to describe his childhood is “precarious.” Growing up on an isolated dairy farm in central Massachusetts, he became accustomed to physical work – feeding cows, harrowing fields, and haying. A life built on farming, dependent on the graciousness of nature, was often uncertain. Careau’s relationship to nature was, as he says, pragmatic. From an early age he learned to use his hands and tools to grow food, fix machinery, tend to cows, and contribute to building a semblance of security in the daily life of his family.

The importance of education

As a way out of their difficult life, Careau’s parents stressed the importance of education, and in 1970 he graduated from Merrimack College with a degree in social science. After college, he worked for two years with emotionally disturbed children in a residential program run by nuns in West Springfield, MA. It was here that Careau first became interested in education and, through a co-worker, learned about the Israeli kibbutz’s collective approach, which resonated with him. He subsequently went to Israel to work on a kibbutz and, while there, met his first wife, who was French Canadian. He moved to Québec in 1973.

In 1975 Careau purchased an old dairy farm northeast of Montréal, which, despite many challenges along the way, he transformed into a seed grain farm and dwarf apple orchard. Careau attributes the development of his problem-solving skills to this experience. “I had to get into a mindset of creative problem solving, to be an inventive kind of person. I started building my own machinery and learning how to manage a business and projecting out five to ten years. I had never before been in a situation where my mind could develop properly for who I was.” Before he became fluent in French, being unable to communicate articulately was an isolating experience for Careau in Québec. With his newly developed technical skills and a desire to express himself more fully, Careau began making sculptures, “bending, carving, and inlaying wood to create curvilinear forms and naturalistic imagery.”

Wood and patterns

Careau attributes much of his approach to making art to what he learned from his father, who eventually left farming for a career as a patternmaker, working in wood for the metal-casting industry. “Wood patterns must be constructed to extremely precise specifications, and as a result, good patternmakers develop a tremendous respect for their tools, materials, and craft. This respect, learned through my father’s example, has shaped how I approach the making of art objects.”

In 1986, Careau made the significant decision to leave farming in order to pursue a career as an artist. After selling the farm, Careau moved to Montréal, where he quickly began showing his work in downtown galleries. Despite his early success, Careau was dissatisfied with simply building and selling his sculptures and wanted to incorporate education and academia into his life.

In 1988 he was accepted at the Milton Avery Graduate School of the Arts of Bard College, earning an MFA in sculpture in 1991. “When I went to Bard, my life really stabilized. I met my second wife on the first day there. I liked the idea of being a part of a community, a community of artists and scholars. I never really had a home as an artist in Canada, it was just build this, sell that. Bard’s program was multidisciplinary, and it suited my mind well. Our closest friends to this day are professors we met at Bard in the late 80s.”

In 1995 Careau was offered a tenure-track position at Columbia-Greene Community College, where he spent the next 25 years directing the fine arts program, teaching, and developing his artistic process.

On view…

Currently on view at TurnPark Art Space in West Stockbridge, MA, are twenty of Careau’s sculptures, in a show titled in the lining of fields. Each individual sculpture compellingly conveys a subtle balance between precariousness and conviction. It’s as if the work itself is a strategic risk, and with thoughtful planning and careful execution, mastery emerges. David Raymond, the director emeritus of the McCoy Gallery at Merrimack College, describes Careau’s work as having a slightly vulnerable feeling yet simultaneously dealing with cognition. Careau’s work is an expression of an interior experience, in that his intrinsic understanding of the world around him emerges through his work. He begins with intention, but opens himself up to risk, and allows the organic evolution of the process to emerge. In fact, he intentionally utilizes risk in order to effectively influence the expression of the sculpture. Here is where Careau’s work evokes both vulnerability and balance simultaneously.

The physicality, the geometric precision, of Careau’s work is evident. His sculptures are built with structural certainty and are attached to the wall securely. But these attachments are minimal, using only what is absolutely necessary so that the pieces stay afloat. They elicit a feeling of detachment, not clinging, and a sense of airiness and spaciousness. Artistic minimalism comes to mind; Careau avoids the unnecessary. It is about simplicity, utility, and elegance.

Interestingly, many of the sculpture’s “arms” can be adjusted to fit the parameters of the room, emphasizing Careau’s ability to pivot, both literally and figuratively, by adjusting his approach to fit the limitations of his surroundings. As a farmer, Careau often had to face challenges, and became an inventive problem solver. Here, Careau anticipates challenges and prepares for them. In this way, he brings a sense of practical confidence to the idea of risk. Careau understands that by approaching problems methodically, you can not only mitigate risk but essentially use it to your benefit to craft something original. Thoughtful balance amidst uncertainty ensures progress.

Interview with the artist Steven Careau

Tell us about your childhood and where you grew up.

I grew up in New Braintree, MA, in a very impoverished situation. My father had been through World War II and four years of combat, and was traumatized by it. My parents came back to the farm after the war to help out my grandfather. The only farms in that area were dairy farms. There were thousands of cows, but it was really a dying enterprise. My grandfather told me that the farm’s best years were during the war, but after the war everything started to fall apart.

I grew up in New Braintree, MA, in a very impoverished situation. My father had been through World War II and four years of combat, and was traumatized by it. My parents came back to the farm after the war to help out my grandfather. The only farms in that area were dairy farms. There were thousands of cows, but it was really a dying enterprise. My grandfather told me that the farm’s best years were during the war, but after the war everything started to fall apart.

Next door to the town where we lived was a factory that made pumps for the navy, Warren Pumps. This was in the 1950s, at the beginning of the Cold War, and there was a lot of work because the US military was expanding. At that time, patternmakers were some of the highest-skilled and best-paid factory workers. The company provided health insurance and a wage that made life somewhat less precarious for our family.

I had a very religious upbringing. Our house didn’t have any books – there was nothing. We worked and that was it. I was twenty years old and in college at Merrimack the first time I ever saw a work of art.

Can you describe your artistic process?

My first requirement is that I not repeat myself. If I’m going to make something, it has to push an idea further and be in some significant way different from what I’ve done before. I don’t do very many works per year. Even in a really productive year, I will do perhaps five pieces. I put all my ideas down on paper as soon as they come to me; I don’t censor them. Then I just let the ideas sit. Sometimes I look back and think, “That’s terrible, what were you thinking,” and sometimes I think an idea has potential merit and I keep it in my notebook. I go back to it later, sometimes a week, sometimes a year later, and ask myself the same question: “Does it have merit?” Oftentimes it doesn’t; often there’s a technical problem. But once in a while an idea will stick. I work very slowly, so I have to be sure of what I choose to pursue. It has to pass the test – that is, that there are no engineering problems in the building of it, no structural weaknesses, and that it sustains my interest visually and intellectually.

How has Suprematism influenced your work?

Suprematism, with its reductive, geometric style, has been very seductive to me. There is a sense of religiosity to it, an icon-like quality, and definite spiritual connotations. The work of Russian artist Kazimir Malevich in particular really speaks to me. The scholar Maria Taroutina has written that his Black Square was intended to replace the fundamental belief system of the culture by creating a movement that would supplant Christianity. I see each of my sculptures as an icon, imbued with a sense of spirituality.

What about Constructivism?

With Malevich you’re given this ideal space, a metaphysical realm, a space that can’t be experienced through our ordinary senses. His work exists in an idealized, extrasensory place. Malevich’s rival Vladimir Tatlin, on the other hand, stayed firmly within the physical world. These two men, in their rivalry, really showed the viewer the two ways we experience the world – physically, through the senses, and conceptually, with the mind. Building on Tatlin’s work, Constructivism focused on utility and rationality. In a way, my work shows the influence of both Suprematism and Constructivism. The pieces have a tool-like or device-like quality, but to what purpose? How are they used? What do they measure? It’s a strange marriage of influences – mysticism and utility.

Tell us about this new show. Is there something specific you are trying to convey through these pieces?

Many of these pieces can be adjusted or reconfigured to suit different contexts or states of mind. They each allow for uncertainty and variability. The pieces in this show seek an answer, but they are really icons of variability and uncertainty. •

To learn more about Steven Careau, visit his website stevencareau.com.

Steven Careau’s show “in the lining of fields” is running May 13-July 31, 2023 at TurnPark Art Space, 2 Moscow Rd., West Stockbridge MA. To learn more visit their website turnpark.com.