This Month’s Featured Article

D.W. Miller & PAleoArt

One thing’s for certain, a dinosaur or ancient fish envisioned and drawn yesterday by a paleoartist may look like one thing today, yet it may look a little different the day after that. It’s tricky business fraught with the possibility of change.

Early in life, paleoartist David Miller, now living and working at the Whatcom Museum in Bellingham, WA, and known professionally as D.W. Miller, had his interest piqued by creatures from the Earth’s past when he saw the life-sized dinosaur recreations created by Louis Paul Jonas in his Churchtown studio for Dinoland at the 1964-65 World’s Fair in Flushing.

“Every kid is interested in dinosaurs. I don’t recall many details – just the sheer immensity of the things. I liked those creatures,” but in time he noticed that while dinosaurs were well-represented in the world of vertebrate paleontology, “other exquisitely beautiful creatures were underrepresented.”

The Ghent, NY, native and 1975 Chatham High graduate had discovered at an early age an ability to draw, or, as he deemed it, “a knack. I have to do this. It’s not really a talent. The course was set. It lacked that sort of conscious decision you might expect. I started doing it and failed to stop. What part of your mind makes those choices?”

Getting going and the break out

Although Miller is today prominent in his field, he’ll be the first to tell you he didn’t just land there. After graduating from Chatham High, he attended the Montserrat School of Visual Arts, in Beverly, MA; moved along to the Art Student’s League in New York City; then spent eight years in New York studying at the Project For Living Artists. For all of that, however, Miller describes himself as “pretty much self-taught.”

The “breaking point” in his career came in 1994, “when a museum off of Central Park was undergoing a major overhaul of invertebrate origins. They needed a bunch of pictures to augment the fossil display. I had already done those and had them on hand. It was a matter of luck.” As is the wont of many artists, Miller said, “I’ve since seen them a couple of times and just wanted to break the glass and get them out to re-do them.”

The “breaking point” in his career came in 1994, “when a museum off of Central Park was undergoing a major overhaul of invertebrate origins. They needed a bunch of pictures to augment the fossil display. I had already done those and had them on hand. It was a matter of luck.” As is the wont of many artists, Miller said, “I’ve since seen them a couple of times and just wanted to break the glass and get them out to re-do them.”

Through the years Miller has done a good deal of work for textbooks and been commissioned by museums around the world. Among the awards he has earned over the course of his career are the Distinguished Achievement Award, Association of Education Publishers for Using Forensics, NSTA Press 2008; Best 2D Artwork, Paleo Art Show, Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, Denver Museum of Nature and Science, 2004; and the Washington State Museum Association Award for Excellence: Centennial Time Machine exhibit, featuring Coast Salish Indian groupings, Whatcom Children’s Museum, 2004.

His work has appeared at the Smithsonian Institution, the American Museum of Natural History, the New York State Museum in Albany, the Florida Museum of Natural History, and the Natural Museum of Science and Industry in London, among a number of others.

“Some of the more bizarre jobs I’ve taken trying to cobble together a living include doing illustrations for a man writing on the Egyptian Kabballa who had to pass his hand over the sketch to see if the gods approved, painting a 30′ rendition of the Statue of Liberty on the side of a house, and developing a line of greeting cards on the theme of high school wrestling for a coach,” Miller said.

“When I was in school, I thought I was going to be a so-called fine artist,” he said. “But I quickly discovered that I didn’t have much to say. People that were better could say what had to be said. So, I wanted to serve science as an illustrator.”

Making the sausage

In an odd sort of twist, Miller “never did much dinosaur work,” but clearly his accomplishments have brought him into the upper echelon of those who work in the field of paleoart. As someone challenged by drawing a stick figure, I wondered, how does one go about giving plausible form to something that existed millions of years ago?

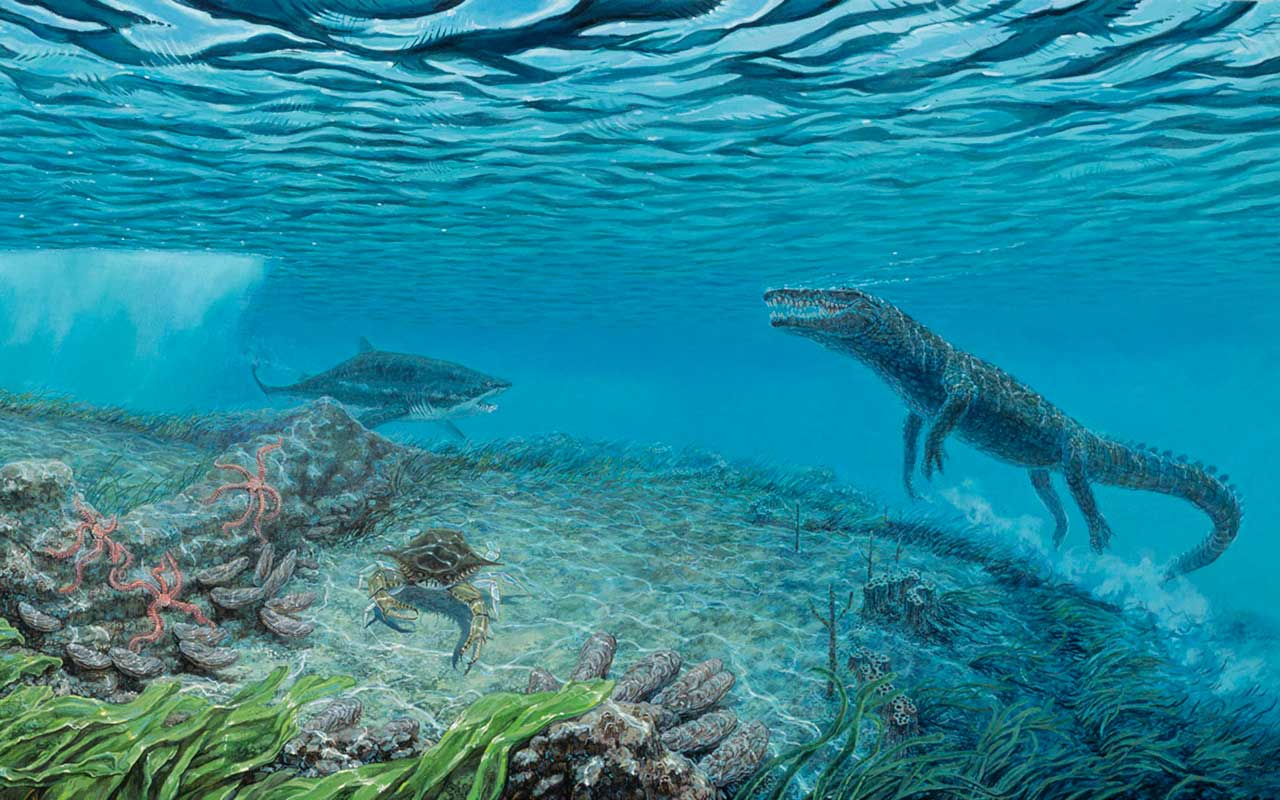

“Typically, it begins with a commission,” Miller said. “The entity, or the scientist, will approach and say, ‘here’s the form we want brought to life in a 2D image, in an environment we know a little about. These are the associated flora (and maybe even fauna) and here’s what we know about the morphology.’ Sometimes there’ll be a skeleton. Maybe even a complete skeleton. And sometimes there will be, in the case of a fish, evidence of scalation, and in some cases, rarely, very rarely, they’ll have evidence of coloration.”

At that point, he said, “They’ll tell me to cook something up, and I’ll come up with a composition. They always supply visual references for me. It’s not like I’m making it up out of whole cloth. They’ll supply drawings or photographs of the fossils for me to bring to life. Sometimes they’ll even supply possible behaviors, so that can be depicted. After that, I’ll do sketch after sketch, and there will be a back-and-forth process. How’s this? What do you think of that? Do I have the form right? Are you okay with what’s happening?”

Ultimately, Miller “comes up with a finished sketch. Okay, here’s how I see it. Sometimes, it involves a dramatic depiction of scale. In 1995, I was tasked to do a megalodon, which is a gigantic shark, but it had to be seen with other sharks, so I thought, how about a massive feeding frenzy with a swarm of sharks eating the flukes of a whale? There is evidence of that. But how do you show the massive size of the megalodon? I thought, the first thing you’re going to see is the various species of sharks. But looming in the background, coming out of the murk, there’s this fantastically sized head – think the scale as coming from front to back, with this huge, nightmarish thing coming in from the background. I didn’t have to show the whole megalodon, but just the head, to show the size comparison. And they went for it.”

Miller said there’s “free rein but not totally free rein. They’re exhaustive with anything to do with the anatomy. But it’s like being a movie director. I can set the stage and show the creature behaving in a certain way. Going in, I don’t usually have a preconceived notion about any of it.”

What’s new

The relatively recent discovery of feathers on dinosaurs has thrown the entire field of paleoatristry into a bit of a tailspin, according to Miller, in that something envisioned less than three decades ago might now have changed. “I’m afraid my deinonychus is now off,” he said with a chuckle.

He pointed to “a really famous case from the Burgess Shale. They found three different fossils. New species, that’s great. It turned out to be a single organism. One fossil they thought was a shrimp, another kind of like a sand dollar, and another animal. It turned out to be a three-foot-long predator. Things are constantly changing. What’s exciting about it is a lot of great painters of years ago have now been superseded” by new discoveries in the field. “It’s always evolving. You work with the understanding that the subject is always subject to new interpretation.”

When the COVID-19 pandemic sailed into our lives in 2020, the Whatcom Museum sent Miller home with instructions to draw “every bird we have. That’s like 550 birds. I worked like the devil. We have a whole floor of nothing but birds: raptors, perching birds, pheasants, owls. It was great. I couldn’t imagine a better fate.”

New exhibition

Over the years, Miller has been allowed to keep many of his original works, which the Whatcom Museum has decided to present in an exhibition set to open in May 2024, work for which is already underway. A sister museum has said it will lend fossils to support his illustrations.

“This has put me on top of the world,” he said. “The planning for this show has gotten me into a state of mind wherein it’s come full circle. I’m completely surrounded by my paintings at work – I’ve had to bring them in for review by the curator. The sketches, the skulls, the ephemera, the maquettes, and the finished works. It occurred to me I have a dog in this race. Wait, I am the dog. It’s cool. All those years of wondering, will I ever make it? And then something like this comes along.”

To summarize his life as an artist, Miller points to the words of Ernest Becker, Pulitzer Prize winning author of The Denial of Death: “Try and fashion something, an object or yourself, and drop it into the confusion.” Miller has since added his own words to that: “and hope for the best.” •