This Month’s Featured Article

Digging Deeper Into Who You Are

Welcome 2021! There is so much about 2020 that we all want to kick to the curb forever. Turning the calendar to a new year feels like a way to make a new start; this is true of all years, but this one especially so.

Welcome 2021! There is so much about 2020 that we all want to kick to the curb forever. Turning the calendar to a new year feels like a way to make a new start; this is true of all years, but this one especially so.

A new year is also a time for reflection, for assessing the pros and cons of our lives and for committing or recommitting to changes that we hope will improve them. One thing about spending so much time alone or with far fewer people in 2020 – and all with this palpable fear of sickness and death that might befall you or your family, friends, co-workers, and fellow human beings if you behave as you did for all the previous years of your life – wow! – is that it provided a time of intense introspection. How could it not?

Someone who knows a lot about digging deeper is Keren Weiner. She’s a professional genealogist, and has been for years. Part Indiana Jones, part Sherlock Holmes, part personal memoirist, Keren knows how to dig to bring the past alive.

Bitten by the Bug of Genealogy

An interest in genealogy was already in her family. Keren’s sister is a professional genealogist, and Keren heard a lot about it from her and was intrigued. When her own daughter went to college, Keren finally had some time to get a taste of genealogical research and, she says, she got “bit.”

Her first big project came in 2003, and working on it she realized it satisfied her on a number of levels. “I love the history, of course,” she says, “and the creativity and writing, but also working with people. When I finish a project I present the work to the family, and it is often an illuminating and transformative experience for them.”

Most of us are familiar with genealogy on a very basic level as the research into a family tree. It conjures up a task of a research project a teacher would have given us in grade school involving hours at the library going through books and documents searching for clues, often finding just names and dates that didn’t really mean anything. Or maybe you have a relative who did some of that research and you have a rudimentary family tree that still is only names and dates on paper.

“When people think about their family tree and wanting to know more,” she says, “what is it that they are longing for? It’s the stories. How did family members manage in difficult circumstances? What were their challenges? The details of their lives show how and why they made their choices.”

It’s these details that Keren uncovers for people.

A longing for stories

“Most of my clients are older,” Keren says, “and they’ve come to realize that they have a lot of questions about their parents and grandparents that they didn’t get to ask, but they still want to know more. Doing the research across the generations does involve going back.” She continues, “but it also involves going across – to second cousins and third cousins in order to get the stories.”

“The names and dates are the ‘what,’ and the rest of it is the who, why, and where – and also the ‘what did that mean’ for someone’s parents and grandparents,” she continues.

“Did you see the movie Contact with Jodie Foster?” she asks. “Foster’s character is in a time travel vehicle, looking out the window and seeing all kinds of scenarios. As she’s looking at all of this, she says in the most profound way, ‘I had no idea.’ That’s what it’s like for my clients,” Keren says.

The role of DNA testing

I have to ask Keren about the DNA testing that has become so popular and what that means for people who are interested in their ancestry. With promises to “uncover stories of your family’s past and find relatives you never knew existed,” it certainly holds great appeal. No wonder the services have proliferated. There’s AncestryDNA, 23andMe, Crigenetics, FamilyTreeDNA – any number of companies that do DNA testing. The reports give you information about your genetic ancestry, others who share your DNA, an ancestry timeline, and even information about health and habits that are genetically related.

These reports in and of themselves can be extremely revealing and life-changing. In the book, Inheritance: A Memoir of Genealogy, Paternity, and Love, by Dani Shapiro (2019, Knopf), she writes about how her DNA test revealed that the man she had known as her biological father for her entire life was, in fact, not. In a review of the book by Heller McAlpin for National Public Radio, McAlpin writes, “With the rising popularity of genetic testing, the relevance of Shapiro’s latest memoir extends beyond her own personal experience. Inheritance broaches issues about the moral ramifications of genealogical surprises… privacy versus the rights…to know [one’s] roots, medical history, and half-siblings.”

In a recent review of the DNA companies for the “Wirecutter” e-newsletter from the New York Times, it was stated up front, “But such DNA testing services also come with inherent privacy concerns, and they’re bound by few legal guidelines regulating the use of your data. The ramifications of sharing your DNA with for-profit companies are continuously evolving, and opting into a recreational DNA test today will likely lead to future consequences that no one has anticipated. If you’re comfortable with that….”

Keren agrees that there is interesting information to be obtained from DNA testing, but she’s quick to point out something few take into consideration: a bigger picture. Any individual only has a certain percent of the DNA from their parents, each of whom only has a percentage from their parents, etc. If you are the only one of your relatives to be tested, you’re only getting a percentage of the story. She directed me to the website support.ancestry.com for an easy-to-understand summary of this issue:

“Many people believe that siblings’ ethnicities are identical because they share parents, but full siblings share only about half of their DNA with one another. Because of this, siblings’ ethnicities can vary. All the genes passed on to siblings come from the same gene pool (that is, the genes of both parents), so each ethnicity passed on to children must be present in one or both parents as well. However, some siblings may inherit ethnicities from their parents that others don’t, and it’s likely that each sibling will inherit different amounts of ethnicities from one another. Children inherit 50 percent of their DNA from each parent, but unless they’re identical twins, they don’t inherit the same DNA as each other.”

“I’ve recommended DNA testing to some clients to address a particular road block,” she says, “but it doesn’t give you enough of the full picture unless another relative or relatives also test.”

History come to life

She also provides me with a wonderful example of what she means by finding the stories behind the names and dates. “My current client is 91 years old,” she starts. “I found a 1923 newspaper article about her grandmother. I was excited to share the article with my client, first because it is harder to find documentation for women than for men and because this particular article was so unusual. It had six headlines!

Auto Bandits in Three More Holdups. Two Men Beaten by Organized Band of Thugs. Quartet of Auto Bandits Blamed for Seven Robberies in Eight Days. Purse is Snatched, Robber Flees as Woman Screams and is Picked Up by Pals in Machine. Saves Ring Loses Purse in Holdup.

“The latter headline was over my client’s grandmother’s photograph. It was a harrowing story, detailing the mugging and describing how a man accosted her on the city street, grabbed her purse and then attempted to get her wedding ring off. The man got away with the purse, but she held onto her ring fiercely. I called my client on the phone and read the article to her. When I didn’t hear an immediate response I asked, ‘Are you OK?’ My client answered, a bit choked up, ‘That ring is on my finger right now.’ She had never heard this story before,” Keren finishes.

Essential research

Keren loves the research that goes into each client’s report. She acknowledges that there is a lot to be found online, but that the work requires much more digging, and this is where someone with even their own strong interest can get derailed. Like any good detective, a good genealogist develops what Keren describes as an “intuitive sense of finding unfindable things.” She adds, “The Association of Professional Genealogists (APG) has guidelines for the professional genealogist to follow. It can be plodding and pragmatic at times, and you have to follow the bread crumbs and take the time to adhere to guidelines for sourcing your work.” Her research projects typically take about six months.

“There are lots of archived materials to go through – records and resources from historical societies, libraries, town halls, tax departments, probate courts. And I have to give a huge shout-out,” she adds, “to the staffs of these places, who are without exception caring and helpful. They love sharing!” Her research often involves records from other countries, and there are genealogists around the world who assist each other with translations and digging deeper. There’s even an organization of volunteers called Random Acts of Genealogical Kindness – raogk.org.

The Final Report

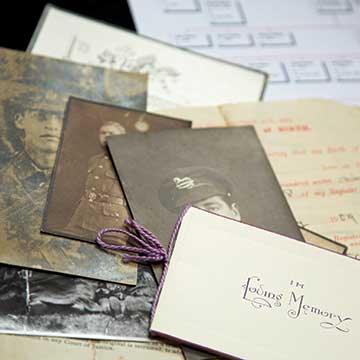

As she works, she puts together timelines and photos and newspaper clippings and photos – whatever documentation serves the stories. She sends the initial family tree to the client so that she’s sure that names are spelled correctly. Then she prepares the final research report and the family is gathered so that she can share the research with everyone. She’s done this in places as varied as living rooms, family reunions held at hotels, outdoor patios – wherever the most people can gather – though this year and for the foreseeable future, it’s by Zoom.

“It’s a very interactive presentation,” she says. “People ask all kinds of questions. It’s quite revealing for everyone to get a sense of their ancestors’ struggles and triumphs. Often, the family is a bit flooded with the amount of information they’ve gotten and things they’ve learned. They need time to process what it means.”

Keren and I both go to the analogy of Jodie Foster’s line from the movie Contact: “I had no idea.”

“It’s funny,” Keren muses, “everyone jokes about finding the horse thief in the family, the particularly colorful character or maybe a villain. But most often it’s the pivotal life-changing circumstances that are discovered in every generation that are the most revealing.” She shares, too, that when this information is shared, the families experience a kind of peace and grounding. To know so much more about the real lives of their ancestors goes to the core of who they are – of who we all are.

The lure and appeal of history

As a lover of history and someone whose job it is to look into the past to understand how people lived in it, I also asked her if there’s a period she’s come to particularly like, one she may have wanted to live in.

“I would have enjoyed the 1890s, the decade leading up to 1900,” she says after giving it some thought. “By 1900 there was a lot percolating in America.” Keren is quick to add that a period she has learned a lot about and that gets her emotional just thinking about is the American Civil War. “The suffering was so profound,” she says, “and made such a mark on this country.” She admires the work of Bruce Catton, the Pulitzer Prize-winning historian and journalist, for how “gorgeous” his writing is about that period.

Bringing It forward for future generations

Genealogy illuminates the past. What does doing this work make Keren think about for people in the here and now? “I’d like people to take genealogy forward in addition to backward,” she says. We all have oodles of photos on our phones and our computers that have replaced traditional photo albums. We get overwhelmed with them and rarely spend the time to properly identify and archive the people, places, and events the way people in the past made photo albums. Genealogists will continue to do research, but there will be less to physically access if the photos aren’t printed out and identified. “The Census used to be full of information,” she shares as an example, “but not anymore.”

“How will our children find our stories,” she muses?

January and the reflective winter months leading to spring seem the perfect time to do this deeper digging. Consider working with Keren on a project. Go through the photos on your phone or social media and start an album. “We hold the legacies of these stories in our hands,” Keren says. This past year may be one we all want to scratch, but our children and grandchildren will want to know what it was like. They will have no idea, unless we bring the stories to them. •

Learn more about Keren Weiner at kerenweinergenealogy.com. Her business is based in Pittsfield, MA.