Featured Artist

I’m Drawing as Fast as I Can

Where do you get your ideas?

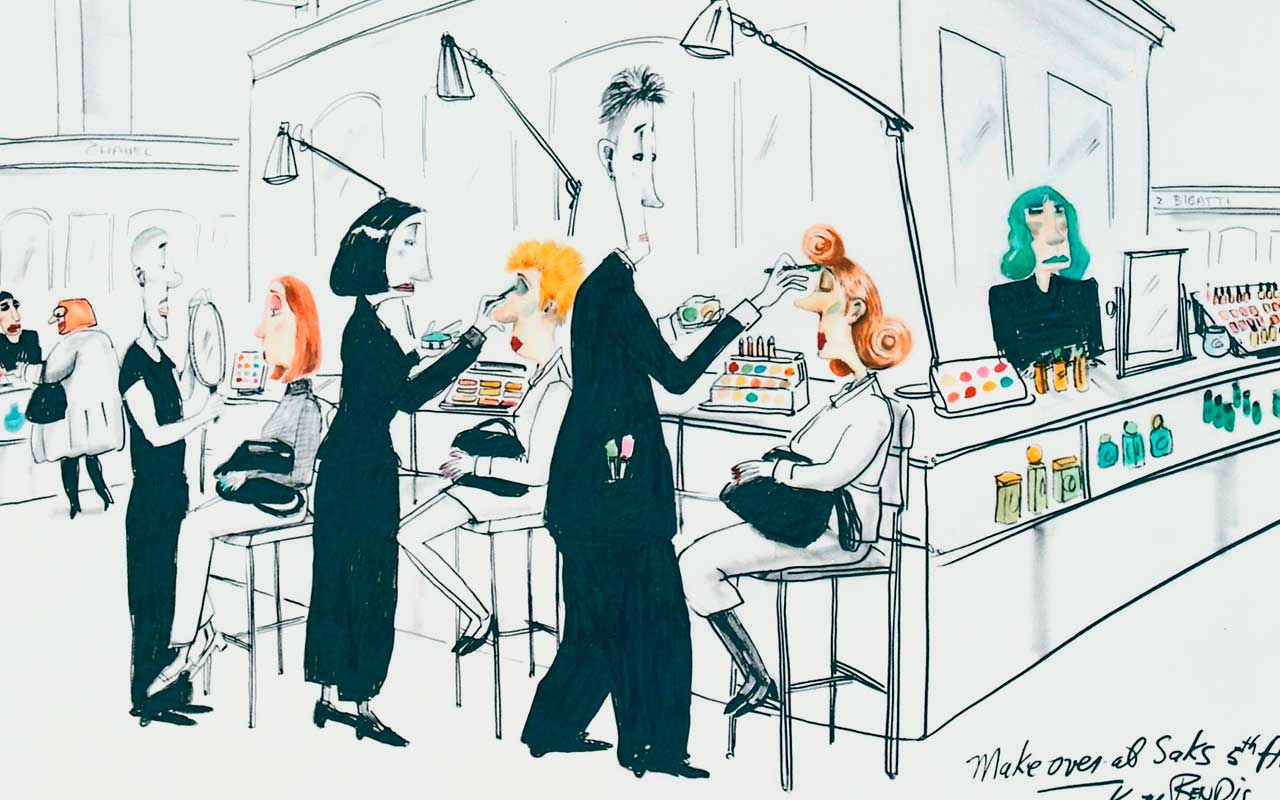

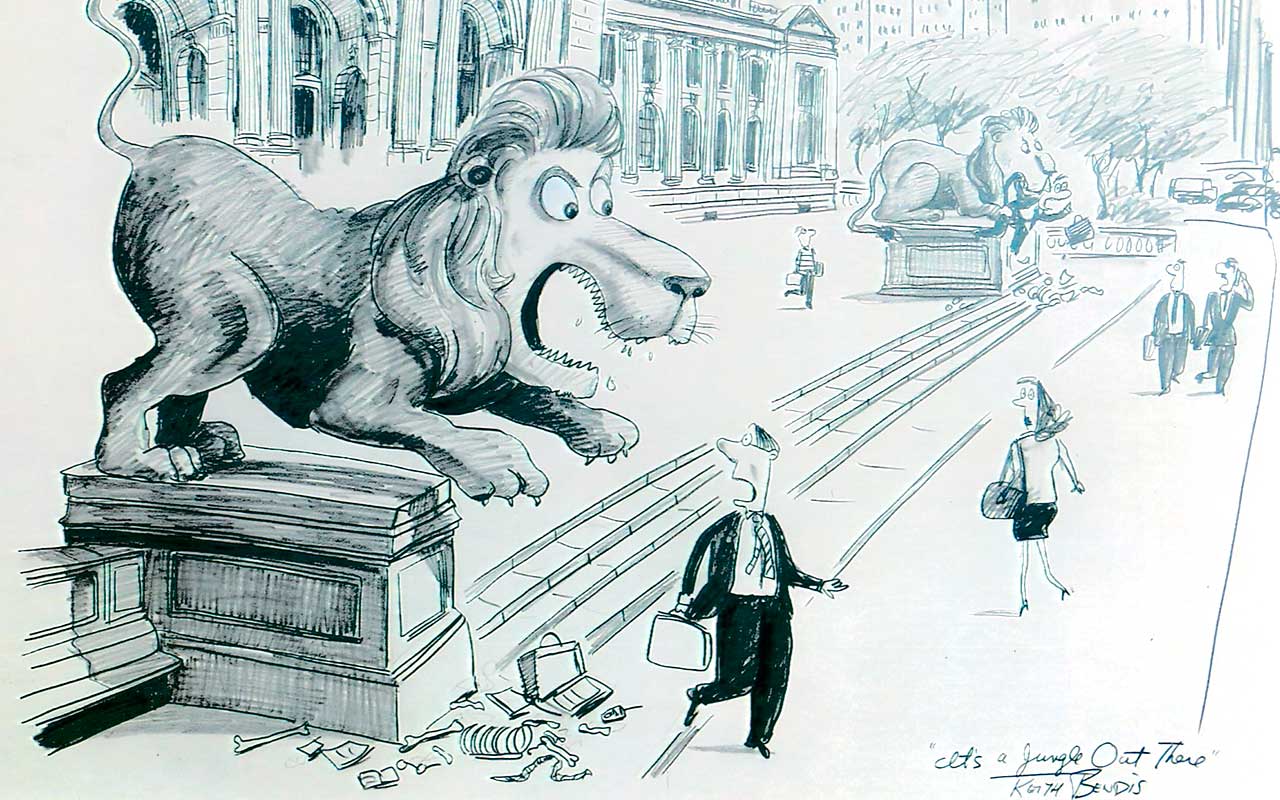

If you look at the world with a satirical perspective, you realize ideas are all around us. When I first came to New York City in the mid 1970s, the latest fashion for women was large, puffy, purple down coats. It inspired me to draw a parade of women in those coats following each other like lemmings off a West Side pier. The drawing led to my first book, Lemmings and Other New Yorkers. After I saw the lions in front of the New York Public Library, I drew a cartoon of them eating businessmen as they walked by. I called the drawing, It’s a jungle out there. That perspective got me a weekly feature in the Sunday Daily News called NY Sketchbook.

Where did you grow up?

I’m from East Carnegie, PA, a small town outside of Pittsburgh. We lived 100 yards from the mill where most of our neighbors worked. My mother was a third-grade teacher, and my dad was a traveling salesman without the drama of Willy Loman. One day in my mother’s class, I drew a horse that actually looked like a horse. From then on, I was the class artist.

How did you become a cartoonist?

How did you become a cartoonist?

My family got The Sunday Times, and from an early age I started looking at political cartoons. I became a fan of Bill Mauldin and Herblock’s work as well as other political cartoons.

I could draw but I never seriously considered trying to make a living doing it. There weren’t many other artists in East Carnegie. Like a nice Jewish boy, I went to law school, which only lasted one year, then I went to night school for art at Carnegie Mellon. I soon became a full-time art student and got a BFA in painting. However, I wasn’t much of a painter. What I really enjoyed was drawing cartoon stories for my friends, who thought they were hysterical.

During art school I spent my summers in Atlantic City working in hotels and restaurants. There was a place on the boardwalk called “Louie Levine’s Artist Village” where tourists could get charcoal or pastel portraits done of themselves. I would go in there and watch the artists, and one day Louie turned around and said, “Hey kid, can you draw?”

I said “yes,”

And he said, “Get someone off the boardwalk and show me what you can do.” I did as I was told, and when I was finished he said, “Okay, you can learn.” Louie gave me the last easel out of 17 and said I could come in on Wednesdays and learn from one of the artists. I worked there for two summers.

Eventually I moved to Philadelphia where I had all kinds of jobs, but I would always go to the train station and draw people. Then I had this brainstorm to go to Nixon’s inauguration in 1972 and do “on the spot sketches” for the underground newspaper The Drummer. I went to the editor with this idea, but he said he was really looking for a political cartoonist. I went to the inauguration, and it was impossible to do sketches because it was so crowded, but I did come up with this very grotesque political cartoon, and the editor loved it. It was the perfect tone for what was going on in the underground press at that time. There was total anarchy. There were no limits on what you could do in regards to biting satire against the establishment.

And that was how I taught myself how to be a political cartoonist. The newspaper came out once a week, and I would do a drawing once a week. It taught me the discipline of having to meet a deadline and having to do caricatures of well-known politicians. I did that for two years, and then I decided to go to New York City with my portfolio of political cartoons, not knowing anything about illustration or what I was getting into.

I moved to New York City, and I started taking my portfolio around to the neighborhood papers, and I started to get work from them. As I was getting better as an illustrator, I started to get better assignments. I had regular work at Harper’s and a column at New York Magazine.

At that time everybody knew everybody. I was a part of this whole stable of illustrators that the art directors would call. You had to know how to work fast and get work done overnight. I was getting better and getting published regularly, people knew who I was.

Then this amazing thing happened. The art director of The New York Times Magazine called me and said they were looking for a new illustrator for the William Safire’s “On Language” column. He gave me three columns to illustrate as a test, to see what I would come up with. I knew this was my big break, and thank god I was able to do it. I did the “On Language” column for eight years.

William Safire was a speechwriter for Nixon. He was the first conservative columnist that The Times had ever hired. As for his politics, he was a little to the right of Attila the Hun, but he was a good writer. On Sundays, he wrote a column about language, in which he would trace the derivation of the latest phrases covering everything from the arts to baseball.

Safire was very famous, and he wrote an important book on Abraham Lincoln. My father and father-in-law are both history buffs, so I called Safire and spoke to his secretary and asked for two autographed copies of the book, and she said no he can’t do it. A year later, one of the drawings I did for the column was of Safire’s Burmese mountain dog, and his secretary called and asked for a copy, and I said “I’ll give you a copy if Bill gives me two signed copies of his book on Lincoln,” and he did.

Every two and a half years Random House would come out with a book of Safire’s column and my drawings. We did three books, which were wonderful records of the column. One day the magazine said they had a new art director, that they were changing the design of the magazine, and that they were going to use a new artist for the column. I was in shock, but there was nothing I could do. When you are working in pop/modern culture, they are always looking for the next best thing. Only a few people in my field have the superior talent that can sustain a career long term.

How did you get involved with graphic recording?

I continued to freelance until a friend told me about something called “graphic recording.” I would attend corporate meetings and, in real time, using my cartooning skills and drawing on large foam boards, I would create a visual record of the meeting. Graphic recording took me all over the US and Europe. I did this for ten years. It was wonderful, but I missed creating my own work.

What have you been working on recently?

Throughout my career I have always looked for book ideas. In 1978, I illustrated the cult favorite, The Fan Man, by William Kotzwinkle. Then I illustrated a book of the baseball poem, Casey at the Bat for Workman Publishers. More recently I illustrated two children’s books, Calvin Can’t Fly and Calvin, Look Out, Calvin, written by my friend Jennifer Bern.

I also recently illustrated The Devil’s Dictionary by Ambrose Bierce, which was published by Fantagraphics Publishing. Since then I’ve illustrated two other books for them – a biting political satire called Only the Good Stay Dead by Joe Queenan and a satirical take on the classic The Art of War, also by Queenan.

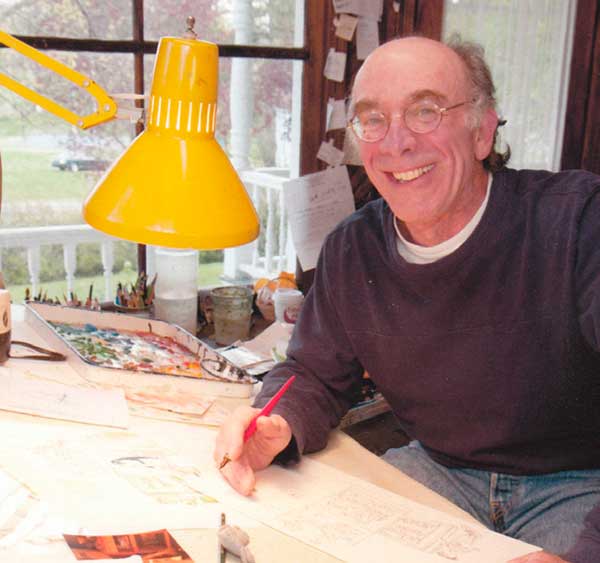

As I get up there in years, I will hopefully be able to continue to work in my cozy studio here in Ancram, NY. My wife, Betzie Bendis, is a wonderful artist and garden designer. She’s my biggest fan and most honest critic. •

To learn more about Keith Bendis, please visit keithbendis.com or email him at bendis@fairpoint.net.