Featured Artist

Meet Patricia Powers, Artist

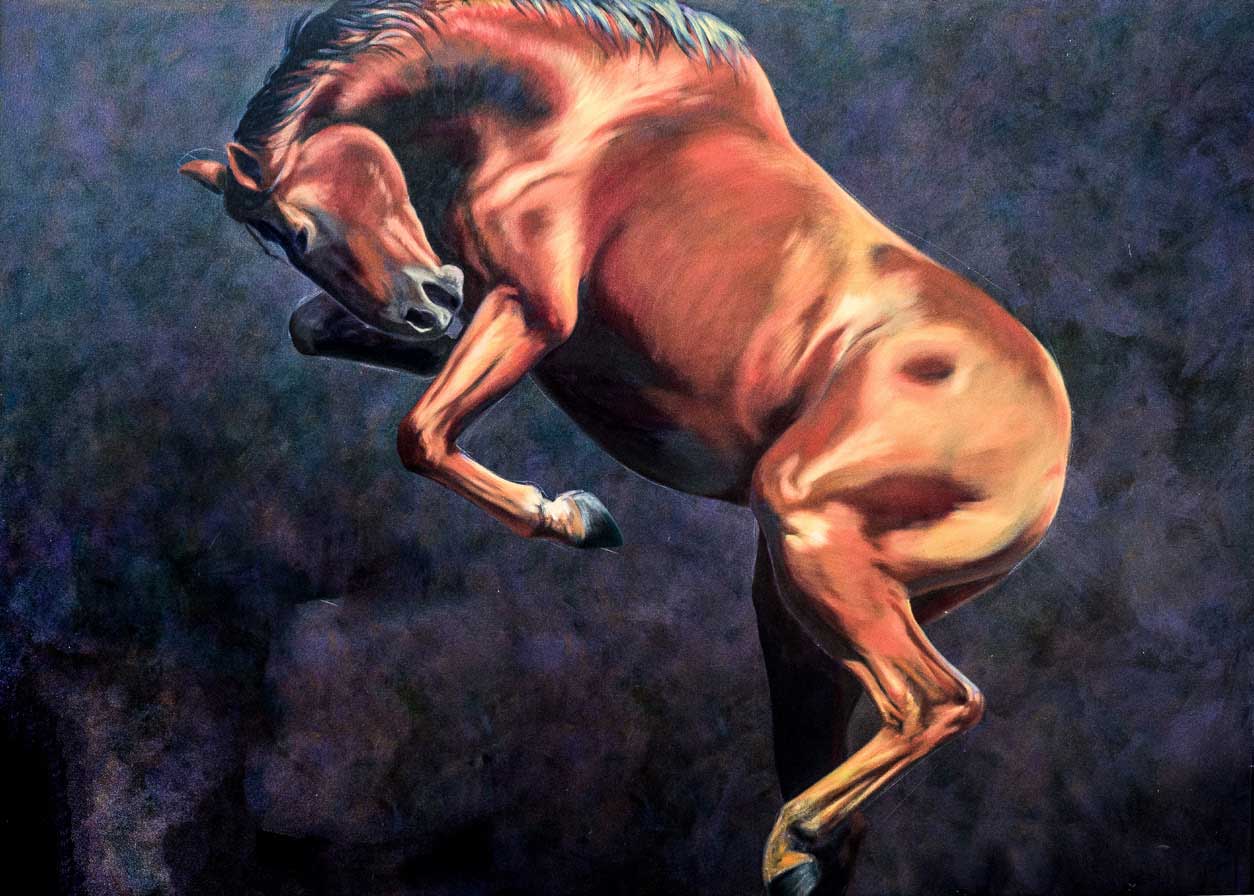

True confession: When I first saw Patricia Powers’s paintings – giant canvases celebrating the beauty and majesty of the horse – my heart skipped a beat. Not just because the work was so powerful and immediate; not just because I, too, have a passion for horses that goes way back; not just because I was enjoying getting to know Patricia through an art book discussion group we were both part of. It was all that, but more. I was startled and awestruck because I had attempted a similar theme in my art school days. I felt I had succeeded with one canvas, though there had been many attempts. Patricia Powers was – is – firing on all cylinders. She has produced many. In fact, huge horses are her signature works. And what works they are.

Patricia has her home and studio in Columbia County, and I was lucky enough to spend some time with her there. The studio is bright and airy with high ceilings that can accommodate her large works. The horses are all around her, and they stop you in your tracks. When I ask where her love of horses comes from, she is quick to share stories.

When horses are everything

“I grew up in Manhattan,” she declares with a laugh, understanding all too well the irony of a congested metropolis as a home for horses. She watched her older sisters ride in Central Park, and went to summer camps where there were horses. “I fell for horses in a ‘typical’ way for girls, I guess,” she says, “but I found that I empathized with them to a degree beyond my love for all animals. I took a horse masters course at camp, and at graduation I was given charge of one of the horses.”

“I grew up in Manhattan,” she declares with a laugh, understanding all too well the irony of a congested metropolis as a home for horses. She watched her older sisters ride in Central Park, and went to summer camps where there were horses. “I fell for horses in a ‘typical’ way for girls, I guess,” she says, “but I found that I empathized with them to a degree beyond my love for all animals. I took a horse masters course at camp, and at graduation I was given charge of one of the horses.”

Tragedy struck Patricia in her late teens when she lost her father to cancer and her mother just a year later. She was declared an emancipated minor at age 17. “In high school I was riding regularly at a farm in Nyack, and when my parents passed I was very fortunate to be able to buy a horse of my own. He became my best friend, my family, and we were together for a very long time. I brought him to the Claremont Stables in Manhattan so I could ride him in Central Park.” She named her horse Brandybuck after a character in Tolkein’s classic, The Lord of the Rings, which her sister, 12 years her senior, had read to her as a child in the 1950s.

Always drawing

Her other passion was art. “I was always creating, making things out of anything at hand,” she says. “I was lucky to attend the High School of Music and Art in New York,” she says, “and then the School of Visual Arts,” but when she had to make a financial decision about pursuing her education or continuing to ride and keep Buck, she chose the latter. She moved to a riding center in Rhinebeck. Patricia’s upper Hudson Valley world of horse people was her sanctuary, though she struggled to make ends meet for herself and Buck. A riding teacher suggested she paint someone’s horse, and she was soon doing commissions for the elite of the hunter/jumper shows, gradually becoming more upset by seeing the way the horses were often treated. Her talent was recognized by a family who offered to pay for resuming her studies, and after extensive research, she decided on the San Francisco Art Institute. Buck went to a retirement farm while she went west.

“The Art Institute was like a monastery of art for me,” she shares, “intimidating and challenging. I wanted to excel for my sponsors, so I went all in. Resuming my studies,” she continues, “I swore to myself that I would never paint a horse again.” Fortunately, my professors, subjected to my rants about horses and cruelty, suggested I return to the subject to help get them out of my system. I did my first large work called Red Hooves (see photo next page), and it was the catalyst to do more.

She began to paint what would be a seminal work in many ways, White Horse (left), an oil on a canvas measuring 86” X 136”. The painting is about “the reality, the vulnerability” of being a horse in relation to people. “A picture I’d seen in a book stuck in my head. It was of a mare ridden to an impossible take-off point for a jump, getting tangled and falling. In the painting, I cut off her tail to make her obviously changed by humans. I wanted the image to be beautiful and shocking, ethereal and real in both size and execution.”

Galleries and shows

The painting got her noticed at the Institute and beyond and cemented her most prolific artistic pursuit. While in graduate school, her works were exhibited extensively around the country. She was swept up in artistic success. In 1984 she attended the Los Angeles Olympics, and watching high-level dressage riding introduced her to a different perspective on competing with horses. The goal with dressage horses is harmony, developed over a long period of time, with meticulous care. It resembles ballet, another of her passions. “I love their big butts,” she says laughing, “the muscles making the horses rounder, and having the arch-shaped forms that appeal to me.”

After eight years based in San Francisco, Patricia wanted to come back east and be a part of the New York City artist scene. She moved into a studio above a barn not far from Manhattan, and she brought Brandybuck with her. She met a man who was also ‘horsey,’ and it was with him that she discovered the quiet of Columbia County, where she’s been for over 30 years. Brandybuck lived to the ripe old age of 27. “I did a few paintings of him,” she says, most notably a piece called My Charge. She continues, “but the theme in my horse paintings is the place horse occupy in the modern world, their subjugation by humans, vulnerability and generosity. The interaction with humans is usually implied in the work in one way or another.”

Hanging on

A cruel twist of fate befell her again when she got back east. To her demise personally and professionally, Patricia developed serious paint poisoning that left her sick and shaken. At the same time, the art world was crashing, and all her galleries went under. Between bouts of ill health, she continued painting and selling privately.

Not long ago, a shoulder limited her movement for nearly two years. For her health and sanity, she started taking long walks near her home. Always looking, she became fascinated by the patterns of vines circling trees. Working from photos that she enlarges and then brings to life with pencil, ink, goache, and even surgical knives, the trees have become a new theme for her. “The irony of the beautiful forms of the vines slowly killing the trees has great pull for me. Some days I identify with the trees, other days the vines. And working on paper which I mount on reclaimed wood planks has a lovely circularity.”

In her studio, with the giant horse paintings forming a cocoon of sorts, Patricia is immersed in art pursuits of all kinds. There are books that have been transformed into themed art journals or scissored into submission, or folded to create patterns. There are works created from chips of dried paint, and everywhere brushes and colors and papers and canvases. There’s an area devoted to jewelry and beadwork – “bead therapy,” she says – where the glass beads and metal strands danced in the sun. There are books on artists strewn about from which she gets inspiration and pleasure. She marvels at works as diverse as the Bayeux tapestries from 1066 to Holbein’s Renaissance works to VanGogh and the Fauves to Hilma Af Klint and Agnes Martin and the Guerilla Girls. What there isn’t is the smell of turpentine or linseed oil. Patricia uses only non-toxic materials, and winces at the recollection of what happened to her before. She’s adamant about safe handling of art materials. “I think toxicity explains a lot about the perception of artists as crazy,” she says. “The paints were poisoning them. Turpentine, solvents, carry pigments through the skin barrier.”

In her studio, with the giant horse paintings forming a cocoon of sorts, Patricia is immersed in art pursuits of all kinds. There are books that have been transformed into themed art journals or scissored into submission, or folded to create patterns. There are works created from chips of dried paint, and everywhere brushes and colors and papers and canvases. There’s an area devoted to jewelry and beadwork – “bead therapy,” she says – where the glass beads and metal strands danced in the sun. There are books on artists strewn about from which she gets inspiration and pleasure. She marvels at works as diverse as the Bayeux tapestries from 1066 to Holbein’s Renaissance works to VanGogh and the Fauves to Hilma Af Klint and Agnes Martin and the Guerilla Girls. What there isn’t is the smell of turpentine or linseed oil. Patricia uses only non-toxic materials, and winces at the recollection of what happened to her before. She’s adamant about safe handling of art materials. “I think toxicity explains a lot about the perception of artists as crazy,” she says. “The paints were poisoning them. Turpentine, solvents, carry pigments through the skin barrier.”

“It’s what I do”

Admirably and courageously, Patricia has stayed focused on making art throughout her life. “This is what I do,” she says, “I honestly couldn’t do anything else.” What brings her joy? “Color,” she says without hesitation. “Also, the way paint feels. And, if you’re lucky, the way a dialogue happens with a work in progress. You have to follow its lead.”

She also loves teaching. “I’ve tried just about everything,” she says. “I love passing on my knowledge. I encourage students to explore and play without self-criticism. Art is in our blood,” she muses, “and it’s going to sneak into our lives one way or another.”

I’m reminded of a line from the movie A Star is Born, where the already successful singer (Jackson Maine) says to the up-and-coming singer (Ally), “Look, talent comes from everywhere, but having something to say and a way to say it to have people listen to it, that’s a whole other bag. And unless you get out and you try to do it, you’ll never know. That’s just the truth.” Art didn’t simply sneak into Patricia’s life, it galloped, bucked, stomped, and kicked. She’s found a way to say something about that, and to do it.

You can view Patricia Powers’s works on her Facebook page, Patricia Powers Artworks, or her website, http://patriciapowers.com. Patricia welcomes visitors to the studio by appointment, and works with students at all levels.