Featured Artist

SUSAN BEE BECKONS US INTO THE UNKNOWN

On May 4 Bernay Fine Art will open The Familiar Unknown, curated by Sue Muskat Knoll and Phil Knoll and featuring 25 artists from the Hudson Valley, Berkshires, and New York City.

Behind every endeavor, whether it is selling art or curating shows, Sue Muskat Knoll and Phil Knoll’s process always begins with the intention to support artists and build community. These past few years have brought about upheaval and changes for most everyone. For their upcoming show, The Familiar Unknown, Muskat and Knoll again bring it back to the idea of community by asking the participating artists to explore what people have had in common these past few years.

In this show, artists are asked to examine the things that we once took for granted yet are no longer assured of. The experience of uncertainty is something we all feel, and instead of displacing us or dividing us, it can in fact unite us.

Artists know only too well that when they are creating artwork they are making conscious decisions as well as opening their subconscious to convey meaning. There are familiar aspects to making art such as which materials artists use, how the materials behave, and what steps it takes to get from the beginning of a work of art to the end. Yet there is also an unfamiliar, ineffable aspect that emerges through the artist’s process of creating, often with a result that is different from what was initially intended. The unknown lives within the subconscious, and art can be a portal for its emergence. It is through this process that artists utilize the “mind’s eye,” which is where our intuition lies. We all have the ability to experience a reality beyond our senses.

Artists know only too well that when they are creating artwork they are making conscious decisions as well as opening their subconscious to convey meaning. There are familiar aspects to making art such as which materials artists use, how the materials behave, and what steps it takes to get from the beginning of a work of art to the end. Yet there is also an unfamiliar, ineffable aspect that emerges through the artist’s process of creating, often with a result that is different from what was initially intended. The unknown lives within the subconscious, and art can be a portal for its emergence. It is through this process that artists utilize the “mind’s eye,” which is where our intuition lies. We all have the ability to experience a reality beyond our senses.

One of the artists in the show, painter Susan Bee, of Brooklyn and Valatie, NY, delves deeply into the subconscious and celebrates her imagination, often recreating archetypes to investigate social and personal struggles. Throughout each of her paintings is an acknowledgement of pain and suffering, yet her mythical creatures, playful patterns, and bright, colorful palette also evoke optimism, humor, and whimsy. Bee mixes heartache with beauty and playfulness.

Ahava = love

For me this is most powerfully demonstrated in Bee’s 2012 work Ahava, Berlin, which depicts a paint splattered, weathered building distinguished by its grand archway. To the right of the archway is a self-portrait of the artist, dressed in green pants and a polka-dot scarf, looking directly at the viewer. The painting was inspired by a trip Bee made to Berlin with her husband in 2012. Unbeknownst to Bee at the time, they happened to be staying near the Ahava Kinderheim, a home for Jewish orphans where Bee’s mother, artist Miriam Laufer, had lived from 1927-1934. After the Nazi’s rise to power, the orphans were relocated to Palestine. When Bee came upon the former orphanage in what had been the East Berlin Jewish quarter, the building was graffitied and war scarred.

Bee uses dripping red paint on the facade to evoke a sense that the building itself has been wounded. The figure of Bee appears small and still, perhaps overwhelmed by the building’s immensely tortured history. Yet, Bee contrasts this with the image within the archway, a scene that is new and clean and cared for. This juxtaposition is central to much of Bee’s work. She acknowledges the pain and suffering of the human experience while simultaneously offering a feeling of hope, clarity, and optimism. The sign just above Bee’s head, “Ahava,” is the Hebrew word for love.

Embracing your demons and beckoning the unknown

Susan Bee’s 2018 painting Demonology was inspired by a 1895 print by James Ensor titled Self-Portrait with Demons. In Ensor’s image, the central figure is a man, seemingly struggling with and being overtaken by demons. In Bee’s painting the central figure is a woman, creating a different relationship, particularly considering the ways women have been demonized in Western culture. Furthermore, in Bee’s version, the demons appear friendly with the central figure, as if they are simply getting to know one another.

Again, Bee asks the viewer to reconsider and celebrate life outside the simplistic black and white. Her work encourages us to step into that which is fearful and unknown and embrace our demons. There is a realism here, an acceptance that the utopian life we all wish for does not exist. Instead, Bee embraces the beauty and authenticity of that which is not always pleasant, both within ourselves and our environments.

Bee’s 2019 Weary Centaur was inspired by Gustav Moreau’s 1890 watercolor Dead Poet Carried by a Centaur. Moreau’s painting, to her, represents “a reflection on the duality of man and the fate reserved for artists.” The centaur and the poet display an opposition, a conflict that cannot be resolved. The death of the poet, both literally and figuratively is at once tragic and explicit.

Bee’s painting, on the other hand, is a more tender and whimsical rendering. The bright blues, reds, greens, and yellows in the background swirl and flow, creating a mythical landscape. The poet, rather than being dead, appears to be sleeping or resting upon the centaur with gratitude, almost as if she is in the arms of her lover, lying upon him with tenderness. Here, Bee channels the angst of the archetype in a slightly more lyrical direction. She recognizes the challenges of being an artist but creates an alternative space to embrace romanticism and joy as well.

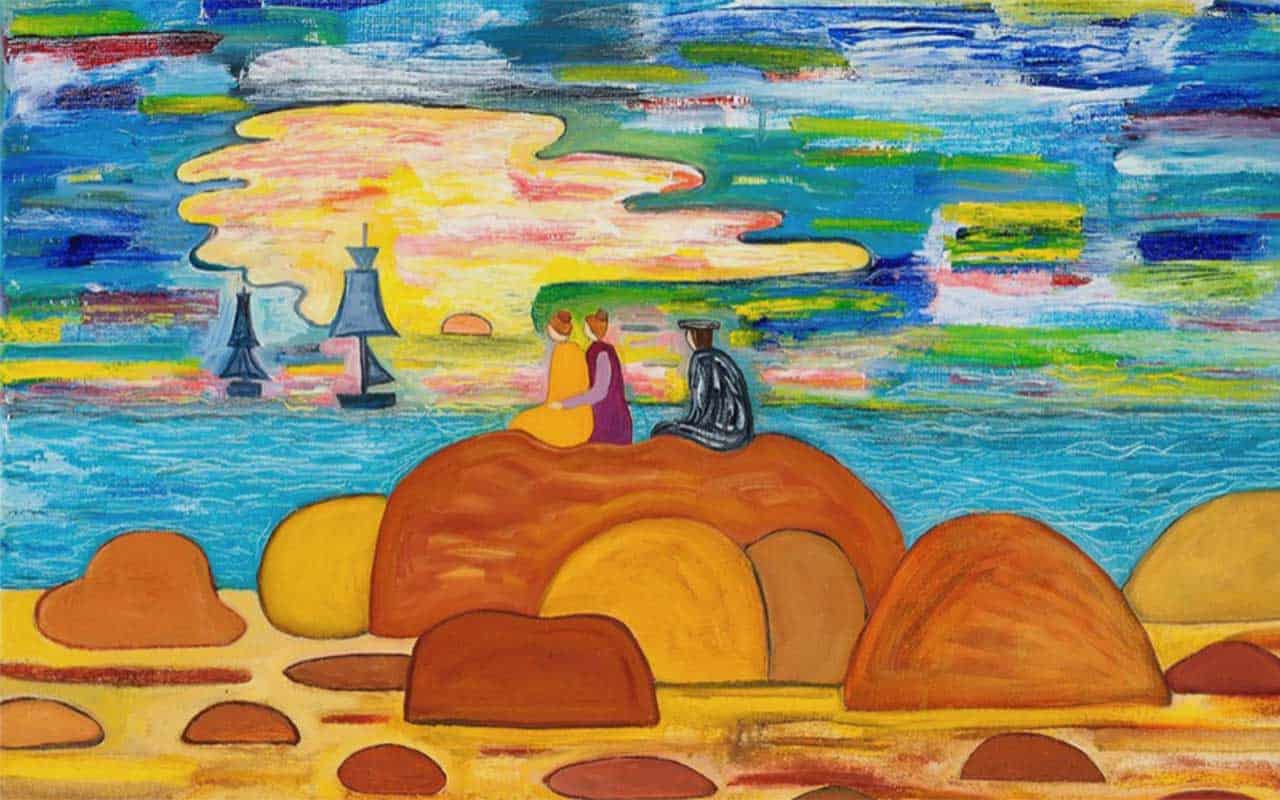

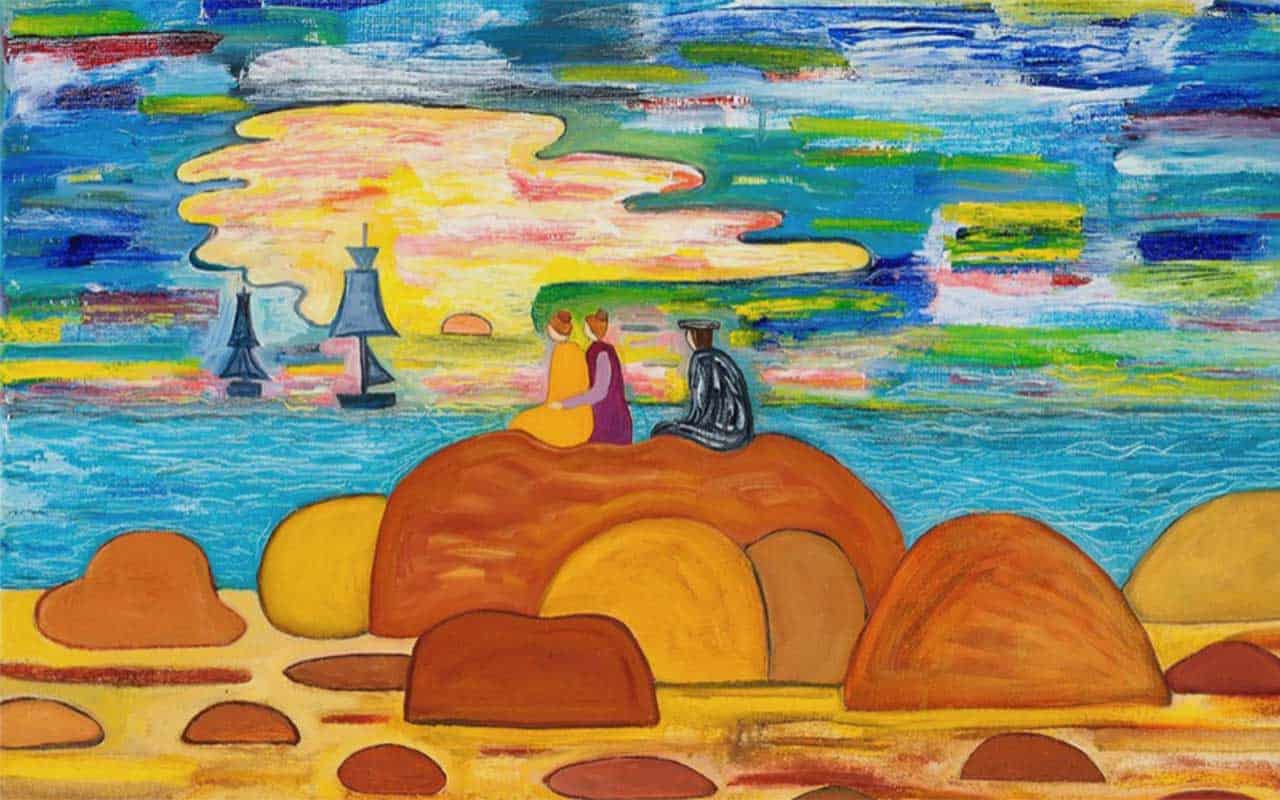

One of the three paintings of Bee’s that Muskat and Knoll chose for the show is titled Moonrise Over the Sea and is based on an 1822 painting by Casper David Friedrich. Both Friedrich and Bee’s paintings depict three people sitting on rounded rocks near the shore, seemingly transfixed by the rising moon, the quiet sailboats, and the gleaming light of the sky and the sea. It is a sublime view celebrating the glorious mysteries of the universe. But whereas Friedrich’s work is painted with a dark palette, Bee’s is bright, once again rendering an archetype in an inviting, hopeful way. She is beckoning the viewer to imagine the unknown.

Interview with the artist:

Tell us about yourself. When did you first know you wanted to be an artist?

I grew up in Yorkville, then a German-Irish neighborhood a few blocks from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. My parents were Jewish immigrants who grew up in Berlin, relocated to Palestine, and then came to Manhattan in 1947. My father was a printmaker, and my mother was a painter. I grew up embedded in the art world; as a child I took painting lessons at MOMA and spent summers in Provincetown, MA.

I went to LaGuardia High School for art, then Barnard for my BA in art history, and then Hunter for an MA in art and art history. I worked as an editor and a graphic designer, and I married a poet, Charles Bernstein, who I met in high school. We had two children together.

I had my first solo show 30 years ago at a commercial gallery in Soho. I’ve had about 20 solo shows in different locations, universities, and colleges. Later on I started teaching at the School of Visual Arts, Pratt, and UPenn. I also had a magazine called M/E/A/N/I/N/G, which was an art magazine that mostly published writing by artists. In 1997, I joined A.I.R., a famous feminist cooperative gallery that was founded in 1972, where I have had ten solo shows.

Both your parents, Miriam and Sigmund Laufer, were artists. Can you describe how they influenced your work?

They influenced me in every possible way. My mother used a lot of color in her paintings, and my father did as well in his graphics, so I was used to seeing a lot of color, and my work has a lot of color. My parents took art very seriously, and we were always surrounded by artists. They thought it was a terrible way to make money, but despite their doubts they did it anyway. It’s like being a monk, if you make the choice that you are going to pursue this lifestyle, then you stick with it.

My parents really didn’t want me to be an artist. I don’t regret anything, but choosing this path requires a certain willingness to put yourself and your work out into the public. You have to be kind of tough, you have to be able to take criticism and rejection. You don’t control the context of how the work is displayed, and you have to be okay with that.

Why are you interested in using archetypes as the basis for many of your works?

I like to take source material that I’m inspired by and then change it based on what I’m interested in in the present-day context. I’m painting for an audience, and I feel like they might enjoy my references and seeing how I’ve changed them. Once I lose interest in a subject, I move on. I’m not good at repeating myself. I did a lot of work based on film noir stills for many years, and before that I used collage in my paintings. Right now I’m obsessed with medieval manuscripts involving apocalypses and saints. I love their iconography. The saints are all heroic women, and they are always defeating the dragons.

You are also an editor, a book artist, and you are married to the poet, Charles Bernstein. Can you describe the ways that literature and art connect for you?

I married a poet, and my friends and collectors are mostly artists and writers. I often collaborate with poets and writers on book projects, including providing illustrations and book covers.

You have said that you identify with Morris Hirshfield’s claim that his paintings are more true to reality than what a camera can do. Can you elaborate on this?

I like to think of my paintings as an enhancement to mundane, everyday reality – I add symbolism, patterns, fantasy, and dreamlike shapes. It’s more true to my reality; my imagination is my guiding force. Being an artist gives you license to do what you want. If I want to make a pine tree red, I’ll do it, and who is going to stop me.

How is your Jewish heritage integrated into your work?

One of my grandfathers was a shoemaker and actor in the Yiddish theater, and the other was a tailor. My parents also worked as commercial artists. My great grandfather was a scribe. I come from artisans, people who made things, and I think of myself as a maker. The outsider artist Morris Hirshfield made shoes and then went from designing shoes to painting. He brought a lot of the graphic knowledge from his shoe designs to his work as a painter. I bring my entire background into my paintings.

What drew you to the Hudson Valley?

I’ve come up here off and on since the 1970s. We have a lot of friends here, and my sister lives nearby. I’m a big fan of the Hudson River School painters. I like the idea of being in the place where these paintings were done. I love being able to look out the window and see the Catskill mountains and the sunsets – it’s very inspirational. •

Apocalypses, Fables, and Reveries: New Paintings, opens March 18 and runs until April 16, 2023 at A.I.R. Gallery, Brooklyn, NY.

The Familiar Unknown opens at Bernay Fine Art in Great Barrington, MA, on May 4, 2023 and runs until June 4. The reception with the artists is on Saturday, May 6 from 5-7pm. Artists in the show include Max Miller, Faile, Amanda Marie Mason, Susan Bee, Jenny Kemp, Matt LaFleur, Wayne Koestenbaum, Katie Rubright,Giordanne Salley, Dan Perkins, Mary Jo Vath, Margot Glass, Colin Hunt, John Franklin, Lindsay Walt, Sally Saul, Peter Saul, Karen Lederer, Judith Braun, Kathy Osborn, Deborah Zlotsky, and Michael St. John.