This Month’s Featured Article

The Dream That Became a Meme: Jaws at 50

51 years ago very few Americans knew much about sharks, much less about great white sharks.

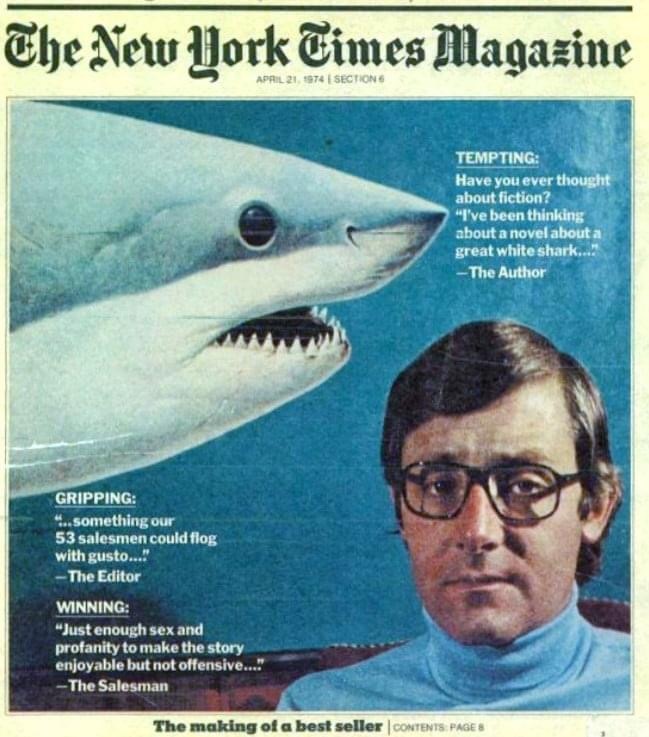

All that changed in early 1974.

A first novel from a 33-year-old writer jump-started awareness of sharks to the point that many people refused to go swimming, or, in some cases, even take a bath.

The creation

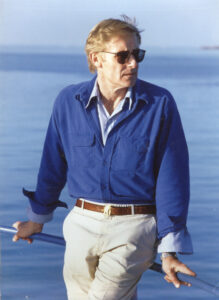

The author of the novel, Peter Benchley (my older brother), said many times that he knew the book would never be a big success, but he just wanted to write and publish a novel. He knew it couldn’t be popular because it was a first novel and a novel about a fish!

After having worked as a low-level speechwriter for President Lyndon Johnson, Peter left gainful employment in 1969 and struck out on his own, with a wife and two children to support.

He blithely ignored the caution of our grandfather, humorist Robert Benchley, who proclaimed that a freelance writer is “someone who is paid per word, or per piece, or perhaps.”

He had always kept two stories in the back of his mind in case he ever got the opportunity to write a novel. Several publishers expressed mild interest, but never enough to commit any money.

In 1971, an editor from Doubleday, Tom Congdon, took Peter to lunch and asked if he had any ideas for novels. Peter laid out his two outlines. Congdon didn’t think much of the idea for a history of modern-day pirates, but he was intrigued at the thought of a large shark terrifying a beach community. So he gave Peter a $1,000 advance for four chapters.

Peter quickly spent the advance and continued on his freelance work.

Several months passed, and the people at Doubleday began to request either the promised chapters or the return of the advance. Since the advance money had long ago disappeared, Peter sat down and cranked out the four chapters.

Unfortunately, he channeled his grandfather and tried to write the story as humor. As he put it “a funny thriller about a shark eating people is, I soon realized, a nearly perfect oxymoron.”

Fortunately, Tom Congdon was patient enough to reject that oxymoron and send Peter back to the typewriter. A month or so later, four acceptable chapters emerged and the story began to take shape.

The story

For the benefit of troglodytes, hermits, the newly-born, and anyone else who may somehow have missed the story of Jaws, a summary would seem to be in order.

Summer visitors flock by the thousands to enjoy the seaside entertainment in the beach community of Amity Island. The small year-round population relies almost entirely on summer revenues from home rentals, fishing boat charters, and other leisure activities.

On a pleasant early July night, a young girl meets a man, has a quick tryst, and decides to go skinny-dipping. He is too exhausted to swim with her.

On a pleasant early July night, a young girl meets a man, has a quick tryst, and decides to go skinny-dipping. He is too exhausted to swim with her.

Her remains wash up on the shore the next day.

The local coroner determines that she died from a shark attack, a very rare occurrence.

The police chief, Martin Brody, decides to close the beaches, for safety’s sake. But the mayor and town council panic about closing the beaches, because they don’t want to drive away the much-needed summer tourist traffic. The mayor is also involved with mob characters who push him to keep the beaches open.

After several more shark attacks, word spreads that Amity is “shark city,” and the visitors stay away in droves. Police Chief Brody closes the beaches.

Mayor Larry Vaughan, whose main business is real estate, tries to pressure the chief to re-open the beaches: “Have you ever tried to sell healthy people real estate in a leper colony?”

The chief requests help from an ichthyologist from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, Matt Hooper. After seeing a tooth that was embedded in a fisherman’s boat, Hooper confirms that they are dealing with a very large great white shark. Unheard of in those waters.

Desperate for a solution that will salvage Amity’s season, the town hires a fisherman who specializes in “monster fish.” Quint is a grizzled loner who has spent most of his life chasing big fish for charter parties. For a large sum of money, Quint agrees to try to capture the offending fish.

Chief Brody insists that he and Hooper go along on the hunt.

And so, the three men board Quint’s boat, the Orca, and set off to chase the great prehistoric dragon. The last section of the book is the story of the details of trying to catch and kill a three-ton “eating machine.”

(In a nod to George S. Kaufman, Robert Benchley’s colleague at the Algonquin Round Table, the novel has occasionally been referred to as “the fish who came to dinner.”)

The final touch

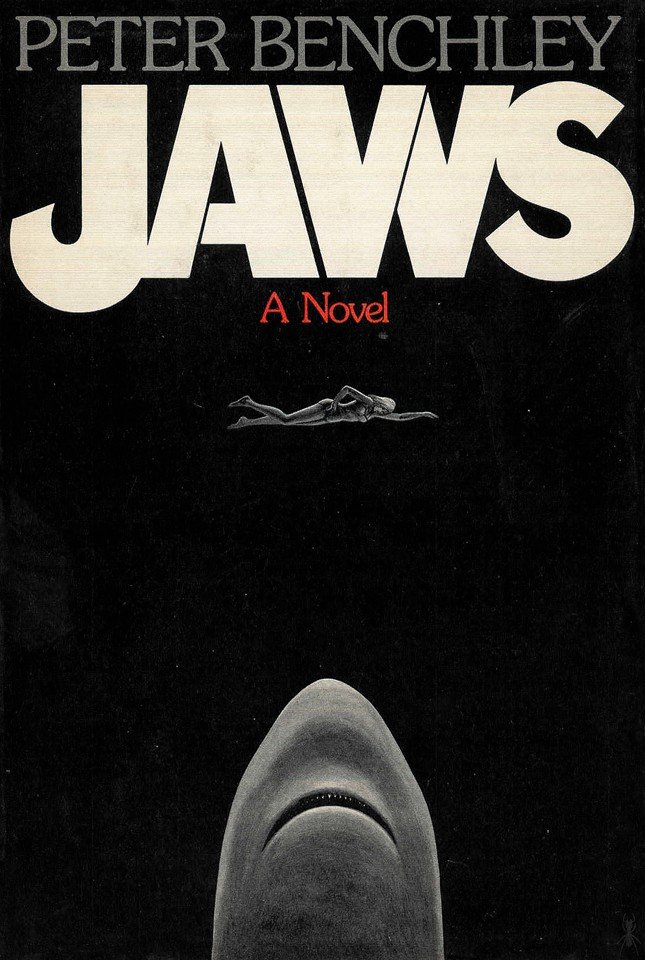

After slaving over rewrites for nearly a year and a half, Peter had not quite figured out what to call the book. On his website (peterbenchley.com) and in the newly-issued reprint of the novel is a list of the scores of options under consideration and the tortuous process of trying to define the story in a succinct title. (One word of caution: a few of the suggested titles are not fit for family reading.)

So, finally, the book was finished and titled and sold to book clubs, digests, and those foolish movie producers who thought they could re-capture the magic on-screen.

The reception

When the book was published in early 1974, it instantly struck a nerve with the public. It stayed on The New York Times’ best seller list for 44 weeks, despite complaints from some critics about the writing or the story.

The adaptation (1975)

When Peter’s agent told him that movie producers were interested in optioning the film rights, Peter was astounded. He knew they couldn’t catch and train an actual great white. And he assumed that the technology at the time was insufficient to make a believable monster. But his agent was smart enough to persevere and advise him to sell the rights (and the rights to unimaginable sequels).

Fortunately, the creative team of Richard Zanuck, David Brown, and Steven Spielberg did not listen to Peter’s cautions about trying to create a monster fish. They persevered through a gruesome summer (1974) trying to make the first ocean adventure actually filmed on the open ocean. Thanks largely to the mechanical genius of Robert Mattey, a special effects wizard who had helped create Walt Disney’s mechanical effects department, they produced the first summer blockbuster thriller.

Spielberg and co-screenwriter Carl Gottlieb had the sense to dispense with several sub-themes from the book (the mayor and the mob, Hooper’s affair with the police chief’s wife) and produce a straight-line adventure story.

And so began the craziness.

The movie became the highest grossing film in history (to that date).

And the general public went wild.

The reaction

As there is no way to account for human behavior, there was no way that any of the participants could have anticipated the manic, insane blood thirst that exploded in this country. People spent untold resources chasing, mutilating, and even killing sharks.

Once Peter and his wife Wendy actually got in the water and met great white sharks, their attitude changed completely. Peter was in awe of the beauty of the beast and the efficiency of its design. After his first cage dive with a great white, he surfaced and stated “we must begin to think differently about these wonderful creatures.”

Once Peter and his wife Wendy actually got in the water and met great white sharks, their attitude changed completely. Peter was in awe of the beauty of the beast and the efficiency of its design. After his first cage dive with a great white, he surfaced and stated “we must begin to think differently about these wonderful creatures.”

So he launched a campaign to educate people about the need to preserve (and not persecute) these magnificent animals.

Still, the success of the book and the movie tended to obscure some of the themes of the original story. The adventure disguised the fact that the many deaths attributed to the shark could have been avoided (after the first victim) if the town had closed the beaches and listened to the experts.

In fact, in the late 1970s, an analogous incident occurred at a coastal town in New England not too dissimilar from Amity: several cases of Rocky Mountain spotted fever arose on one small island. The board of the local cottage hospital debated whether or not they should report it to the Centers for Disease Control. When the side favoring not reporting it because it would affect the rentals for the rest of the summer won the argument, one board member stood up and said, “Have you not learned from the lesson of Jaws?” and promptly resigned. The outbreak did not get reported until late August.

The aftermath

Peter and Wendy devoted the next thirty years to championing environmental causes specifically related to the oceans and shark preservation. Peter’s words were carefully crafted to reflect Wendy’s attention to policy and pragmatism.

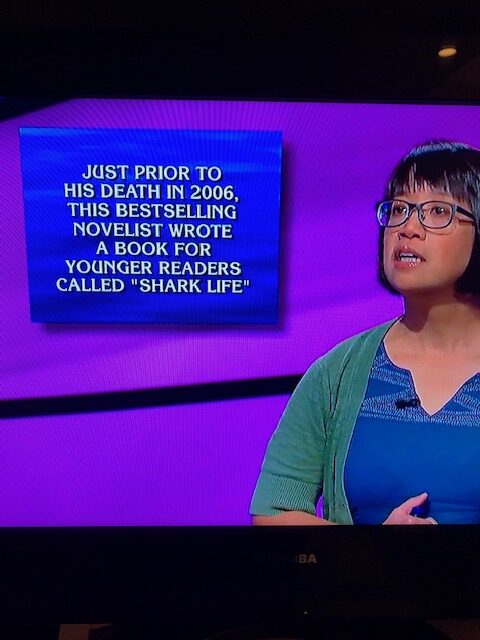

Peter died in 2006, but Wendy marches on carrying the campaign around the world. She was a big factor in instituting bans on the odious practice of shark finning (mostly for shark fin soup). And for ten years she administered the Peter Benchley Ocean Awards, which were often referred to as the “Academy Awards for the Ocean.”

Interest and admiration for sharks has grown exponentially in the past few decades. People now appreciate the sheer beauty and efficiency of these prehistoric creatures.

In 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic began to spread and public resistance to treatment rose for a variety of ill-informed reasons, editorials and other think pieces cropped up all over the world decrying the willful ignorance of “the lesson of Jaws.” The underlying theme rose once again to remind people of the book’s prescience.

And since there is still no accounting for human density, Britain’s ITV television production house has announced that this year they intend to produce a “reality” show in which “ocean-fearing ‘celebrities’ are brought face-to-face with a series of increasingly scarier sharks.”

What could possibly go wrong?

Fortunately, numerous books are available for those who care to educate themselves about the reality of sharks. To name just a few favorites, Carl Gottlieb’s The Jaws Log is the most thorough, fact-filled telling of how the movie survived all the impediments to become a blockbuster. As Peter said in the 25th anniversary reissue, Carl’s stories about the making of the movie are “how it was.”

And, for a series of scary, amusing and informative stories about life around and among sharks, Peter has left us Shark Trouble. It has been described as combining high adventure with practical information in a book “that is at once a thriller and a valuable guide to being safe in, on, under, and around the sea.”

In a lovely tribute to Peter, a newly-discovered type of shark, the “Ninja lanternshark” was officially named Etmopterus benchleyi in 2015.

So Peter’s dream of just getting a novel completed has now spent fifty years entertaining, scaring, educating, and amusing people all over the world.

Not bad for a first effort.