This Month’s Featured Article

The Railroad’s Lasting Impact

Railroads are, for the most part, an almost forgotten part of life in Dutchess County. Oh sure, we can still hop onto a Metro North train and travel to New York City from stations to the south. But the enormous influence the iron horse once played in the area’s economy and everyday life are only memories, stories and photographs in books.

Railroads are, for the most part, an almost forgotten part of life in Dutchess County. Oh sure, we can still hop onto a Metro North train and travel to New York City from stations to the south. But the enormous influence the iron horse once played in the area’s economy and everyday life are only memories, stories and photographs in books.

Some individuals strive to keep those memories fresh. John Henry Low (an appropriate if serendipitously bestowed name by his parents) is one of these. I had the pleasure of speaking with him at length about the history and significance of the railroads that crisscrossed the county at one time, bringing with them goods and passengers to Millerton, Amenia, and Pine Plains and other towns, while allowing local residents to travel to pretty much anywhere in the United States.

“Trains, to a great extent, democratized travel, at least down to the middle class because they could afford the tickets. The poorer people still couldn’t because they were expensive for them at the time.” Prior to the arrival of the railroads you traveled by foot, horse, horse-drawn carriage, or boat (the latter, of course, had limited flexibility). Even traveling at their initial speeds of ten miles an hour, trains were much faster than any other mode of travel, except perhaps for a galloping horse (but how long could the steed keep up a fast pace?) or an ice boat on the Hudson River during winter. Trains slowly inched up their speeds and were travelling in excess of 60 miles per hour after the middle of the 19th century.

“Suddenly, people could travel from Dutchess County to Los Angeles by train if they so desired,” said Low, a Pine Plains resident who has given lectures on the history of the area’s railroads. “And the railroad became the way the hauled goods to market long distances.”

The Poughkeepsie Bridge

The building of a Poughkeepsie railroad bridge in 1888 was to have a dramatic effect on east-west travel by rail, and its construction was spurred by the railroads. Prior to the bridge being built, coal from Pennsylvania travelling to industries and homes in the Northeast and New England had to be off-loaded from train cars west of the river by shovel, with the coal then shoveled into a barge to cross the Hudson River, and then shoveled again by hand into waiting gondola cars, since coal hoppers had yet to be invented.

By building the Poughkeepsie Bridge, which was then the longest cantilevered bridge in the world, an engineering marvel of its day, the process was greatly simplified and coal (and anything else) could now travel east by rail unimpeded. Once the coal was delivered in New England, manufactured goods would then be loaded on freight cars for the travel back west to eagerly waiting markets and consumers.

The railroad changes Dutchess County

By the middle of the 19th century, railroads had also become vital links from agrarian Dutchess County to New York City and beyond, hauling produce and products from the many farms that once dotted the landscape. There were enormous dairy farms and farmers sent their produce for years via railroad. For instance, nine farms were established in what is now called the Coleman Station Historic District by emigrants from New England in the late 18th century. Over the course of the 19th century they evolved from farms that primarily raised a diverse group of livestock for local and regional markets to dairy farms that used the station and the railroad line that ran through the middle of the district to sell raw milk to New York City. By the middle of the 20th century a “corporate farm” in the district had become one of the city’s largest milk providers.

“They would have used the trains to send their milk to market,” observed Low of the area’s dairy farms. “Most dairy farms actually sold their milk to a creamery, such as Borden’s and Sheffield Farms, and there were others. Most of the towns around here, including the small ones, would have had a creamery right next to the tracks, many with a spur or siding track. Some creameries were essentially bottling plants.”

According to an article on the Harlem Valley Rail Trail’s (HVRT) website there was a Sheffield Farms Creamery in Coleman Station. “So, that milk would have headed down the New York Central’s Harlem Line to New York City. On the way, it would have been interchanged to go down the Hudson River Line from Spuyten Duyvil. But milk was definitely loaded in Coleman Station.”

The advent of passenger trains also resulted in a bustling tourist business as city folk sought the natural benefits of Dutchess County’s countryside and farms. Many individuals opened their homes to travelers, who might stay a few days, a week, or the summer. Indeed, the homes and farms were listed in a hard cover book called Summer Homes, somewhat like tourist brochures of today. The book touted the properties for rent, as well as sights to see and things to do in Dutchess County.

According to the book, a Mrs. Charles Smith opened up her Millerton “Maple Villa” to travelers, charging $7 to $9 a week on 1898. Children were allowed after an “application” for them was submitted. And a Mrs. Van Rensselear had a 12-room home that brought $125 a month and $500 for the season, which one assumes was the summer. The bed and breakfast establishment had been born, thanks to passenger trains coming north, west, and east.

How It Happened

According to the HVRTA’s website and with due deference to historians Heyward Cohen, Jack Shufelt, and Lou Grogan (The Coming of the New York and Harlem Railroad, Pawling, NY: Louis V. Grogan, 1989), in 1852, the New York & Harlem Railroad was built north to Chatham. This completed an extension of the railroad more than 125 miles northward from its origins in Manhattan. Products were transported by rail directly to New York City rather than depending on river transport via Poughkeepsie. The extended line also provided a rail route for people and commerce northward to Albany, Boston, and towns in Vermont and Canada.

The historians said the New York & Harlem Railroad originated in the 1830s as an early commuter railroad linking lower Manhattan (New York City) with the affluent new “suburb” of Harlem in northern Manhattan. In the early 1840s, businessmen pushed for an extension of the railroad much farther north after Boston was connected to Albany via the new Western Railroad of Massachusetts. Albany was the terminus for both the Erie Canal to the west and the newly constructed Buffalo-to-Albany New York Central Railroad. New York City businessmen worried that Boston would have a competitive advantage over New York City for the expanding “western trade.”

“By the early 1840s, the New York & Harlem Railroad had been extended northward into Westchester County,” according to the website report. “In 1845, the New York State Legislature authorized a further extension northward to create a connection with Albany. An inland route up, what later became known as, the Harlem Valley was chosen. The valley route was easier and less costly to construct than a route following the Hudson River.

However, business interests in important cities along the Hudson River, such as Poughkeepsie, soon raised the capital to construct a second railroad line, the Hudson River Railroad. This competing project was completed to Albany at almost the same time as the New York & Harlem Railroad and wound up becoming a rail primary route.

Both railroad lines were acquired by Commodore Vanderbilt in the 1860s and became part of the “rail baron’s empire,” stretching from New York City to Chicago and St. Louis. The northern portion of the New York & Harlem Railroad became the Harlem Division of the New York Central & Hudson River Railroad, later shortened to New York Central Railroad. In 1968, the Harlem Division became the Upper Harlem Line of the new Penn Central Railroad. The series of swamps, floodplains, and valleys from Brewster to Hillsdale later became known as the Harlem Valley because of the New York & Harlem Railroad.

According to the report, the upper portion of the New York & Harlem Railroad became a secondary line (the Harlem Division) in the Vanderbilt New York Central Railroad empire. “Nonetheless, it remained important to the transportation needs and commercial activity of eastern New York State and western New England for over 100 years.”

The Central New England Railway and others

The Central New England Railway played a significant role in Dutchess County travel and commerce. It ran from Hartford, CT, and Springfield, MA, west across northern Connecticut and across the Hudson River on the Poughkeepsie Bridge to Maybrook, NY. It was part of the Poughkeepsie Bridge Route, an alliance between railroads for a passenger route from Washington to Boston, and was acquired by the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad in 1904.

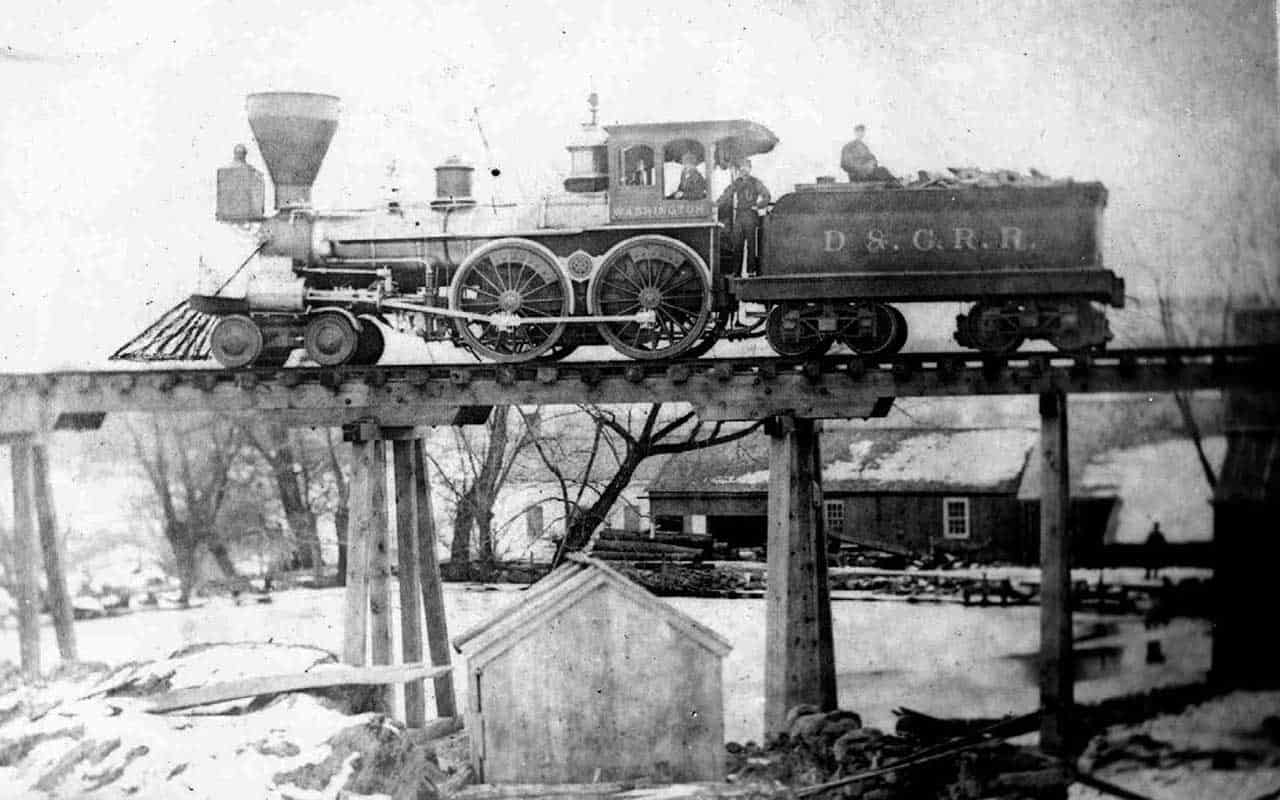

According to the website www.classicstreamliners.com, the Connecticut Western Railroad was chartered in 1868 to run from Hartford, CT, west to the New York state line, where it would meet the Dutchess & Columbia Railroad (D&C) just east of Millerton. The line was completed in 1871. The previous month, the company had leased the easternmost bit of the D&C to gain access to the New York & Harlem Railroad at Millerton. The only branch was a short one in Connecticut, south into Collinsville, which would not be completed until December, 1874. The Connecticut Western became bankrupt in 1880, and in 1881 it was reorganized as the Hartford & Connecticut Western Railroad.

Said Low, “The Rhinebeck & Connecticut Railroad (R&C) interchanged with the Poughkeepsie and Connecticut (P&C) in Silvernails, a hamlet outside Pine Plains. Sometimes the R&C was fondly called the ‘Huckleberry Line,’ as it slowly meandered across the top of Dutchess County and stopped to allow passengers to collect huckleberries that grew alongside the tracks.”

The R&C was organized in New York on June 29, 1870 to build from Rhinecliff on the Hudson River east to the Connecticut state line to join the Connecticut Western. The line opened to the public in 1875, running from Rhinecliff east to Boston Corners, NY. From Boston Corners to the state line, the R&C obtained “trackage” rights over the track of the Poughkeepsie & Eastern Railroad, which junctioned with the Connecticut Western and Dutchess and Columbia at the state line.

In 1882 the Hartford & Connecticut Western (H&CW) bought the R&C, giving it a line from Hartford to the Hudson River. The Poughkeepsie, Hartford & Boston Railroad, the successor to the Poughkeepsie & Eastern, went bankrupt in the 1880s, and in 1884 the H&CW outright bought the line east of Boston Corners that it had operated under trackage rights.

Getting back to the Poughkeepsie Bridge. The Poughkeepsie Bridge Company was chartered in 1871 to build the bridge, and the first train crossed the bridge on December 29, 1888. The Hudson Connecting Railroad (P&C) was chartered in 1887 to build southwest from the bridge, and about the same time the Poughkeepsie & Connecticut Railroad was chartered to continue the line northeast from Poughkeepsie. The bridge company had hoped to acquire the Poughkeepsie, Hartford & Boston Railroad, but was unable to, and so chartered the P&C to run parallel, ending at the Hartford & Connecticut Western Railroad at Silvernails, NY. The connections were not completed until 1889, and on July 22 the two approaches merged to form the Central New England & Western Railroad (CNE&W).

That same year the CNE&W leased the H&CW, giving it a route from Hartford all the way across the Hudson River to Maybrook and Campbell Hall, NY. Maybrook/Campbell Hall soon became a major junction point for many railroads transferring cars to the CNE&W. The Delaware & New England Railroad was also formed in 1889 as a holding company to own the CNE&W and Poughkeepsie Bridge Company.

In 1890, the CNE&W chartered the Dutchess County Railroad to run southeast from the east end of the bridge in Poughkeepsie to Hopewell Junction, the west end of the New York & New England Railroad (NY&NE) at the Newburgh, Dutchess and Connecticut Railroad (ND&C). The line opened May 8, 1892, giving the NY&NE a route to the bridge.

The Reading Company (RDG) bought the CNE&W and Poughkeepsie Bridge Company from D&NE in January 1892, extending RDG’s influence to New England via the Pennsylvania, Poughkeepsie & Boston Railroad. The two companies merged on August 1, 1892 to form the Philadelphia, Reading & New England Railroad (PR&NE). RDG proved unable to handle its new acquisitions, and PR&NE defaulted on its interest payments in May 1893. The final reorganization came on January 12, 1899 with the formation of the Central New England Railway (CNE).

The New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad, also known as the New Haven Railroad (NH), acquired financial control of CNE in 1904, mostly for the Poughkeepsie Bridge and western connection at Maybrook that it would soon develop to its full potential. CNE was allowed to operate separately, but the lease of the Dutchess County Railroad was assigned to NH on December 1 to allow its access to the bridge. The Newburgh, Dutchess & Connecticut Railroad and Poughkeepsie & Eastern Railway (P&E) acquired by the NH in 1905 and 1907, were both assigned to the CNE and merged into it in 1907 (along with the Dutchess County Railroad).

The ND&C gave CNE a route from Millerton southwest to the Hudson River at Beacon, intersecting the Dutchess County Railroad at Hopewell Junction, and P&E ran parallel to the main line from Boston Corners southwest to Poughkeepsie. By 1915 the former NY&NE from Hopewell Junction to Danbury, CT, would also be transferred to CNE.

In 1910 the Poughkeepsie & Connecticut main line was abandoned in favor of the parallel Poughkeepsie & Eastern Railway from Pine Plains southwest to Salt Point where the two lines had crossed The P&E used trackage of the Newburgh, Dutchess & Connecticut Railroad (also merged into the CNE in 1907) from Pine Plains southwest to Stissing. Connections were built at both ends of the abandonment.

The former P&E was abandoned from the Ancram lead mines northeast to Boston Corners in 1925; along with the concurrent abandonment of part of the former Newburgh, Dutchess & Connecticut Railroad to the south, the old Poughkeepsie and Connecticut Railroad and Rhinebeck & Connecticut Railroad was the only remaining route of three from Pine Plains to Connecticut. On January 1, 1927 CNE was finally merged into NH.

With the economic ravages of the Great Depression, more lines continued to be closed or abandoned in the coming several decades. In 1932, the former Rhinebeck & Connecticut Railroad was abandoned from Copake (north of Boston Corners) southeast to the state line, cutting the CNE in two.

At the time of the 1969 merger of the NH into Penn Central, all that remained of the original CNE was the westernmost section, from Maybrook over the Poughkeepsie Bridge and southeast along the Dutchess County Railroad to the former NY&NE as well as the easternmost portion to Bloomfield, CT. The westernmost section was part of the Maybrook Branch, continuing east over former NY&NE and other lines to Derby. With the 1974 fire that closed the Poughkeepsie Bridge, the Maybrook Branch was abandoned west of Hopewell Junction. In 1976 the remaining line became part of Conrail. The Connecticut Department of Transportation later acquired it. And in 1999, the contemporary Central New England Railroad acquired the 8.7 mile Griffins Industrial Track near Hartford.

Millerton Station

Millerton station was located on the NYC Harlem Division, originally the New York & Harlem Railroad. Tracks first reached Millerton after 1848, and reached the end of the line in Chatham in 1852. The NY&H was acquired by New York Central and Hudson River Railroad in 1864 and eventually became the Upper Harlem Division of the New York Central Railroad. The station included a passenger station and a freight station, and also served the Newburgh, Dutchess and Connecticut Railroad, and a spur from the Main Line of the Central New England Railway. In 1911, the NY&H passenger station was replaced by a new station built by the New York Central.

Passenger service ended at Millerton on March 22, 1972, with the New York Central’s successor Penn Central winning a court battle to end its unsubsidized train service north of Dover Plains. Freight service continued, though the station itself was closed permanently by the winter of 1975. The New York State Department of Transportation subsidized freight service between Millerton and Wassaic until March of 1980 when the line between Wassaic and Millerton was abandoned. The tracks were removed during the summer of 1981.

Low shared an interesting tidbit about a reported last freight train shipment to Millerton. “The CNE tore up their tracks as they lost customers. The line back to Hartford had been severed in Lakeville, as they took down the bridge that crossed Route 41 between the Lakeville Station and heading east. They had a single customer in Millerton, which I believe was the lumber yard that is now the Herrington’s. The lumber yard where Herrington’s is was uphill from the CNE’s interchange with the New York Central. The interchange track was north of current NYC station building. A freight car would be dropped off by the NYC at the interchange track. Then the CNE used a tractor to pull the car uphill to the customer’s siding track. When it was time to send the car back (empty) to the interchange, a brakeman would ride on the car by the brake wheel and (hopefully) control the speed down the hill.” This was what apparently took place on a last shipment to Millerton.

Causes for abandonment

According to the Harlem Valley Rail Trail report, railroads in Duchess County, and, of course, elsewhere met their demise because of new highways, turnpikes, interstates, a changing economy and new lifestyles that caused a decline in traffic and revenues on the Harlem Division. This led to service cutbacks and deferred maintenance, which then caused further loss of business, both freight and passenger.

Service was extended in 2000 back to Wassaic from Dover Plains. MTA’s Metro-North has upgraded the Upper Harlem Line and constructed new facilities located just north and outside of the hamlet of Wassaic. Although the Upper Harlem Line was abandoned and the track removed between Wassaic and Millerton and on northward to Chatham by 1981, the Harlem Valley Rail Trail began preservation of a linear corridor for alternative public use. The Poughkeepsie Bridge that was crucial in fueling the Northeast’s powerful manufacturing base for so many years, was abandoned after the 1974 fire and now is an impressive walking trail.

The past can still be seen

While train whistles are only echoes from the past in Dutchess County, relics from its past remain, such as the former train stations in Millerton that now serve as homes for businesses and preserved stations, like the Pleasant Valley station that was moved to the Dutchess County Fairgrounds, and the Canaan Union Station, a grand building that was restored after a fire and now houses several businesses and a railroad museum. Other notable nearby museums are in the Hyde Park, NY Station and the Hopewell Junction, NY Depot building, said Low.

“If you know where to look you can see other traces of the railroad in the area,” said Low, such as bridge abutments, culverts, right-of-ways that once were covered with tracks, foundations of water towers and structures, the several former stations, freight houses, and shanties. “There are even a few small stations I know that are on private properties that serve various purposes.”

Low explained that before the 1969 Penn Central merger, railroads in the United States were never significantly subsidized by Federal or local governments, the way virtually all rail service (passenger and freight) is subsidized in Europe and Asia. Not only do the railroads have to maintain their own infrastructure of track, signals, stations, etc., but railroads are charged real estate property taxes on their track right-of-way, station houses, and other infrastructure, just like any private home or business pays for property taxes. By contrast, trucking, airlines, and many ships operate on roads and airports and seaports that are ultimately paid for or subsidized by the taxpayers. And in Europe and Asia railroads are subsidized or owned by governments or government agencies, whose policies find the railroads to be a preferred and efficient form of transportation that relieves congestion and promotes smart development.

But we still have memories and all those stories and old photos, as well as some regional sightseeing service on restored trains. Thanks to individuals such as Low and many other train historians like RW Nimke, who wrote what is considered by some a definitive study of the Central New England Railroad, and Bernie Rudberg, who whose book titled 25 Years on the ND&C (Newburgh, Dutchess & Connecticut), as well as countless others, the past remains an accessible part of the present.

And if you want to get a close up look and a wonderful guided tour of the former rail lines and terminals, you can take part in the Central New England Railway (CNE RY) “2020 Bus Trip,” scheduled for March 29 of next year. The bus tour is held every year in early spring before the leaves are on the trees so participants can get a good view of the former paths the railroads took to their destinations.

Each year, the group covers a segment of the old CNE, taking about nine trips over nine years to cover the entire route. Next year’s trip on “The Poughkeepsie Bridge Route,” will cover the section from Norfolk, CT, through Millerton and points in between, on Sunday, March 29 starting at 9am. A 55-seat coach bus with a PA system will be employed. The cost of $55 includes lunch at the Canaan Union Station, as well as coffee, muffins, and 200-page guide books – written mostly by the late Bernie Rudberg, Jack Swanberg, Lee Beaujean, the late Ed Hootowski and others – prior to the start of the trip.

For questions about the trip call Joe Mato at 917-232-1555, or email joemato&sbcglobal.net. •