This Month’s Featured Article

Alive with Energy Edvard Munch – Trembling Earth at the Clark

The Clark is on a roll. Last summer, it gave us a spectacular Rodin exhibition, and this summer’s stunning visual feast is Edvard Munch: Trembling Earth. In a word–go!

The Clark is on a roll. Last summer, it gave us a spectacular Rodin exhibition, and this summer’s stunning visual feast is Edvard Munch: Trembling Earth. In a word–go!

The collection will reward you with richly hued multi-dimensional explorations of Munch’s relationship with the natural world that go far beyond his iconic and ubiquitous The Scream. Munch’s ardor for forests, shores, and cultivated natural spaces transcends their physical beauty. His paintings, sketches, and prints reflect his spiritual and energetic connections to nature and acknowledge its healing powers.

Back to Nature

Norwegian artist Edvard Munch (1863-1944) is better known for his somber and poignant explorations of separation, loss, death, and loneliness – those are not the subject of Trembling Earth. Clark Associate Curator Alexis Goodin elaborates, “This exhibition is an exciting opportunity for visitors to get to know a different side of Edvard Munch and enjoy viewing his paintings and prints closely. I hope our visitors will revel in the brushwork and color choices Munch made in his paintings. These aspects add meaning to the works, which appear strikingly fresh and vibrant in person.”

Goodin remarks that this is the first exhibition to focus on Munch’s relationship with and interpretation of nature and his enduring attachment to the natural world. Indeed, part of the Clark’s 2022 strategic plan involves a greater interweaving of its programming with the woodland and meadow it occupies. “Munch’s connection to nature, as explored in the exhibition, makes sense for the Clark given its setting in the Berkshires and its 140-acre campus,” says Goodin.

This exhibition has been ten years in the making, starting with the efforts of Dr. Jay Clarke, who, until 2018, was the Clark’s Manton Curator. Her move to the Art Institute of Chicago didn’t end her relationship with the Clark. She is the museum’s guest co-curator for this exhibition, a powerful collaboration between the Munchmuseet in Oslo, Norway, and the Museum Barberini in Potsdam, Germany.

Human and Nature

Edvard Munch was a prolific artist, producing thousands of works during his lifetime. He bequeathed his collection to Oslo at his death, giving birth to the expansive Munch museum, the source of many of the show’s works.

Munch witnessed the industrialization of his home country of Norway. He experienced the cramped, airless city life juxtaposed with time spent in Norway’s awe-inspiring forests, fjords, and shorelines.

Early trauma also influenced Munch as he endured the premature deaths of his mother and sister. These events found their way into his portrayal of human loneliness and separation, featured in his portrayal of human figures.

Munch battled mental illness and depression and turned to nature to heal himself. His art and writing explore the spiritual and scientific dimensions of the natural world and his belief in the energetic qualities of animate and inanimate objects.

Into the Woods

Into the Woods

Munch’s paintings of forests are lush in color and lavish in their brushstrokes. He pays homage to a mystical and pragmatic forest, showing levels of interconnection between humans and trees. Goodin describes Munch’s fascination with themes of nature’s mysteries, links to myths and fairy tales, and the interplay of industry and aesthetics. She comments, “Some of his trees are abstract, immediate, and stylized, showing us the always-changing nature of trees.”

The Fairy Tale Forest’s towering and darkly painted trees, rendered against a darkening sky bruised with purple, exude energy, but is it foreboding or adventurous? Two small children pause in a clearing readying to take the next step into woods that are alive with possibility, mystery, and perhaps some danger. In the foreground, a hatted head watches on. Is it there for support as the children take that first step into the unknown, or is it afraid to walk with the guileless children, knowing what they might face?

The Yellow Log and The Logger show human activity in otherwise tranquil forest settings. The first painting that greets you in the exhibition is The Yellow Log, centered on a felled tree that seems to extend into infinity. Munch understood how deep our reliance on forests ran, and witnessing the Industrial Revolution in Norway, he visually expressed how forests sustain us on every level, even if that means their destruction.

Mixing Labor with the Land

Munch portrays how we use the earth to fulfill our physical and spiritual needs. He bought a cottage and property outside Oslo and relished planting and tending gardens and orchards. It sustained him body and soul.

In works such as Spring Plowing, we see a Munch that is “fluid and confident in his brushwork and generous with paint. Some areas of the canvas are also visible,” describes Goodin. She elaborates on “Munch’s desire for viewers to respond emotionally to his work and to imbue his paintings with a sense of quivering energy.”

The painting gives a colorful carnival quality to the horses pulling the plow. For Goodin, “Munch was interested in turning the earth into something productive, and there is energy and movement in the horses.” Their brightly colored and heavily painted muscles strain as they look to pass right before the viewer.

Winter Whites

SEveral paintings pay homage to the long Norwegian winter. Munch uses cool blues and whites to give snow dimensionality as it covers the landscape. In winter, we must wait patiently for nature to emerge from its rest and accept our lack of control over this seasonal process.

Winter in Kragerø shows a dark green tree, the only sign of life, standing sentinel over a snow-covered town at rest. It was a view Munch returned to many times in his paintings.

Sand and Shore

Munch grapples with his philosophical and spiritual sides through work representing shorelines. While viewing Summer Night by the Beach and Beach, Goodin observes, “For Munch, the border between land and sea was alive with possibility and was always shifting and changing.” She points to the vibrantly colored and thickly painted rocks lining the shore, “They have a quivering, animated quality.” In Munch’s view, all beings and objects, animate and inanimate, are alive and connected. The shoreline is a liminal or thin space between worlds.

Munch used a roofless outdoor studio to blur the lines between his painting and the natural world. He sought the opportunity for “chance and accident to inform his paintings. He frequently left canvases outdoors exposed to the elements,” explains Goodin. These close encounters of the natural kind pose challenges for conservators today. An example is Bathing Men, painted at the beach with evidence of sand affixed to the canvas.

Here Comes the Sun

Munch’s grand and kinetic The Sun shows the sun radiating and boring through the landscape. Munch saw the sun as the life force in all things and believed that organic and inorganic objects are intimately and energetically connected. Any divisions between living and non-living are arbitrary and created by a human need for categorization.

Other works in this section expose Munch’s attempts to grapple with religion and spirituality, his pious upbringing, his exposure to Darwinist theories, and his experiences of awe and healing in the natural world. It includes the sketch The Human Being and its Three Power Centres, his description of which gives the exhibition its title.

Dropping a Pin

Munch shows himself to be a lover of place. His homes and gardens became the subject of themes he reworked, experimenting across seasons, with changing light and perspective, and with and without human subjects. He experienced these places as retreats from people and the crush of urban living.

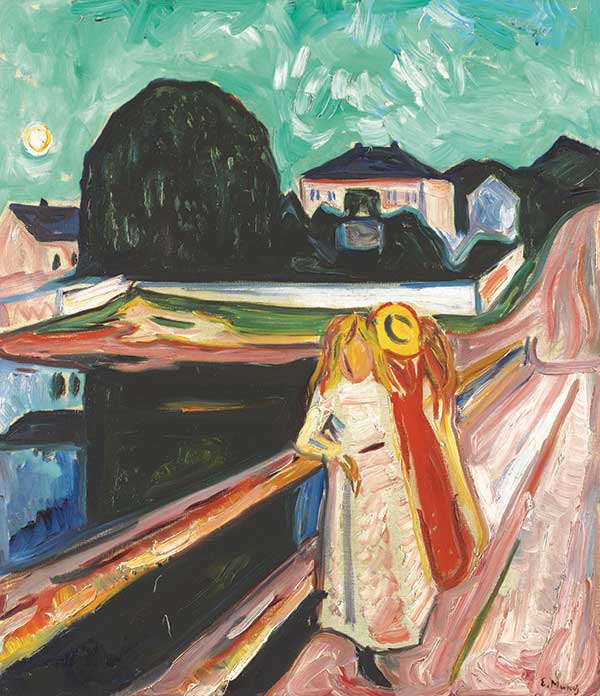

His numerous studies of girls and women on a bridge near his cottage in the fishing village of Åsgårdstrand, located on the Oslo Fjord, vary in seasons, times of day, and clusters of figures conspiratorially huddled, their backs to the viewer on a long bridge.

Yes, It’s There Too

If a Munch exhibition would only be complete for you with The Scream, then Trembling Earth has that, too, in the form of a black and white lithograph. When you view it, instead of focusing on the howling visage, focus on the undulating lines and shapes of the land, sky, and seascape behind him. These are juxtaposed with the straight lines of the human-made bridge extending to the left, leading two figures away from our field of vision.

Make a Connection

As you wander through the show, ponder the profound connection between all beings and objects in the natural world that defined Munch’s work in this show. Then carry those thoughts out of galleries to the reflecting pool and network of woodland trails. It will make the show even more visceral and impactful.

See what Munch saw – healing, connection, glimpses of the sublime, impermanence, and an experience of awe. Trembling Earth is a show we need. It’s Munch’s call to connect with the sublime, heal what’s broken, be one with the natural world, and get in touch with our deeper selves. •

Edvard Munch: Trembling Earth runs through October 15 at The Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, MA. Visit clarkart.edu for more information. You can also explore the exhibition on the Bloomberg Connects app at bloombergconnects.org.