Local History

Close to Home: Slavery in Columbia County

-by the Hillsdale Historians

Black History Month spurred us to investigate the institution of slavery in the Hudson Valley and, more specifically, Hillsdale. Like most Americans, we’ve been inclined to think of slavery as largely a Southern institution. But it was hugely important in the colonial North. From the earliest days of Dutch occupancy right up to the Civil War, much of New York State’s bustling economy benefited directly from traffic in enslaved humans.

In the 17th and 18th centuries New York was second only to the southern states in its number of enslaved people. In 1703, 42 percent of New York City’s households had slaves, much more than Philadelphia and Boston combined. Among the cities of the original 13 colonies, only Charleston, South Carolina, had more.

In the Hudson Valley, the first enslaved men were brought to Fort Orange (Albany) in 1626, only two years after it was settled, by the Dutch West Indies Company. By the mid 1600s Dutch ships were bringing thousands of men women and children in chains to New Amsterdam, many of whom were sold to upstate landowners to work on the vast farms and manor holdings of the Anglo-Dutch elite. Enslavement was not only a source of cheap labor (since settlers were hard to come by in the Hudson Valley) but also cheap capital.

In colonial Columbia County, the majority of enslaved people were concentrated in the older river towns of Kinderhook, Clermont and Claverack, held for the most part by the Dutch, the Germans, and Anglo-Dutch landholders. In Kinderhook, roughly a quarter of the white households owned slaves in 1790. Robert Livingston, the third lord of the Manor, ruled a literal plantation, with some of the forty-four slaves working at his ironworks at Ancram. In 1786 there were more than 1300 slaves in Kinderhook, Claverack, and Clermont, comprising 10 to 13 percent of those towns’ total population.

In sharp contrast, the Yankee-settled hill towns of Hillsdale and Canaan along the Massachusetts border had far fewer enslaved people. In the first Federal census of 1790, enslaved Africans counted for less than one percent of the population of Hillsdale and Canaan. It is tempting to imagine that the hill town Yankees – emigres from Massachusetts, which had abolished slavery in 1784, and Connecticut, which has passed an act for Gradual Abolition in 1784 — were more high-minded than their riverfront neighbors. But more likely they were just poorer, working as tenant farmers on the Livingston or Van Rensselaer manors, a condition of servitude unlikely to enrich them to the point where they could afford to buy enslaved people. Those who weren’t tenant farmers were considered “squatters” by the Van Rensselaers and Livingstons and were in constant danger of being chased back over the border by British troops at the behest of the great landowners.

Americans won their freedom from Great Britain in 1785 but did not extend that freedom to people of color (or women, for that matter). The first halting steps toward abolishing slavery in the state were being taken in New York as early as 1785 but were heatedly contested. Columbia County was split on emancipation. The anti-abolitionists were rooted in the riverfront Dutch/German communities where slavery was a fundamental part of the agricultural economy. The pro-abolitionists encompassed both the thriving city of Hudson, settled by Quaker whalers from New England, and the populist Baptist militants of the eastern hill towns of Canaan and Hillsdale, where slavery was much less entrenched.

That is not to say that there were no enslaved people in Hillsdale. The 1790 census shows a total of 66 enslaved people in Canaan and Hillsdale, compared to 978 in Kinderhook and Claverack, and 386 in the south-county Livingston towns. Charles McKinstry, a prominent Hillsdale figure and member of the NY Legislature, held five, and Ambrose Spencer (of Spencertown) held three. But both men, conscious of evolving anti-slavery sentiment, voted against their financial interests to support the abolishment of slavery in New York.

After nearly 15 years of State Legislature squabbling, New York passed a gradual emancipation act 1799. It freed no one immediately; only children born to enslaved people after July 4, 1799 would be liberated, and only after they served a lengthy indenture for many years. Practically, the system amounted to a form of remuneration for lost slaves, since freed children were often bound back to their former masters. An 1817 law went further, freeing slaves born before July l4, 1799. But it did not go into effect until July 4, 1827. And children born to enslaved mothers before July 4, 1827, would be indentured for 21 years. These two laws reflected compromises with pro-slavery financial interests and were intended to protect slave owners by drawing out emancipation over generations.

After nearly 15 years of State Legislature squabbling, New York passed a gradual emancipation act 1799. It freed no one immediately; only children born to enslaved people after July 4, 1799 would be liberated, and only after they served a lengthy indenture for many years. Practically, the system amounted to a form of remuneration for lost slaves, since freed children were often bound back to their former masters. An 1817 law went further, freeing slaves born before July l4, 1799. But it did not go into effect until July 4, 1827. And children born to enslaved mothers before July 4, 1827, would be indentured for 21 years. These two laws reflected compromises with pro-slavery financial interests and were intended to protect slave owners by drawing out emancipation over generations.

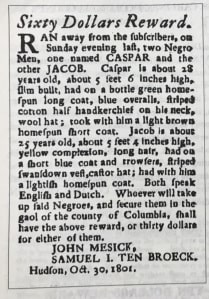

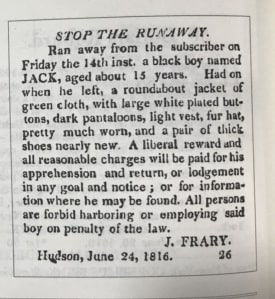

Still, New York became a haven for slaves escaping from Mid Atlantic and Southern states. The militancy of the hill towns may have helped shaped the operations of the underground railroad in Columbia County, where stations in Hudson, Chatham, and Austerlitz hid fugitives coming up the river from New York. Advertisements offering rewards for escaped slaves tell a sad story.

Then came the federal Fugitive Slave Law in 1850, which nullified New York’s personal liberty laws and required state officials to help slave catchers and punished those who helped escaping slaves. Free blacks had to be on guard against gangs of kidnappers who would seize free men and women, falsely claim they were escaped slaves, and ship them south to be sold.

As pro- vs. anti-abolition sentiment roiled the country in the run up to the Civil War, Columbia County stayed largely in the anti-abolition column. Martin Van Buren, the 8th President, was called the quintessential “northern man with southern principles” by a black newspaper correspondent passing through Kinderhook, whose Washington allies were on a par with “the sultan of Constantinople, or the autocrat of St. Petersburg.” More interested in holding on to power than resolving the question of emancipation, he lasted only one term in office. By 1840 the black communities in Hudson, Troy and Albany began to publish publications like the Northern Star and Freeman’s Advocate, the National Watchman and the Clarion, mobilizing African Americans in New York State galled by their nearly total disenfranchisement.

The Black population in Columbia County was stable or declining between 1820-1860 as freed African Americans left farms for cities or struck out for more fertile western lands when the Erie Canal opened. When the Civil War finally came, Columbia County was ambivalent, and efforts to raise a regiment failed in 1861. But Blacks in the county took the first opportunity to join the fight against slavery. Early in 1863 Colonel Robert Gould Shaw of Boston raised the first regiment of Black soldiers for the Union Army, the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts, largely from Berkshire County. All told, twenty-five Black Columbians served in the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts.

Hillsdale has a somewhat tenuous connection with one of the founders of the NAACP. Thomas Burghardt (born in West Africa around 1730) was held in enslavement by the Dutch colonist Conraed Burghardt in the Housatonic Valley. Thomas briefly served in the Continental Army during the American Revolution, which may have been how he gained his freedom during the 18th century. His grandson Othello in 1811 married Sarah Lampman, who was remembered by her grandson as “a thin, tall, yellow and hawk-faced woman” originally from Hillsdale. That child, born in 1868 and brought up in his Burghardt grandparents’ Great Barrington household, was William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, the famed civil rights activist, prolific writer, scholar, sociologist, educator and a co-founder of the NAACP.

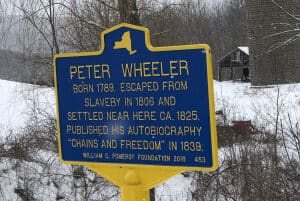

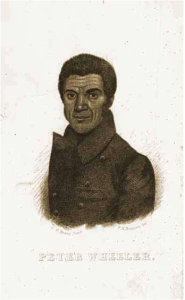

On Dugway Rd. in Austerlitz, a marker denotes the approximate location where Peter Wheeler settled circa 1825. Born into slavery in 1789 and freed as a child in the will of his owner, Wheeler was sold into slavery at age 9, enduring unimaginable brutality from his slaveowner until escaping in 1806 for a life on the sea. He wrote his autobiography, Chains and Freedom; or, The Life and Adventures of a Colored Man Yet Living, a Slave in Chains, a Sailor on the Deep, and a Sinner at the Cross, in 1839. You can read it online here.

Follow the Hillsdale Historians and see their latest blog posts as well as past stories by signing up here.

References:

New York State Museum http://www.nysm.nysed.gov/research-collections/archaeology/historical-archaeology/research/archaeology-slavery-hudson-river

Columbia Rising: Civil Life on the Upper Hudson from the Revolution to the Age of Jackson, John L. Brooke, University of North Carolina Press, 2010