Local History

Collecting Forgotten History

Alexandra Peters gave me a private tour of her sampler collection on display at the Sharon Historical Society through October just after this enthralling exhibition opened in June. It was a very personal introduction to the art and meaning of needlework samplers which reveal the lives of American girls and their families from 1700 to 1850. The professionally hung show with informative explanations begins with English maps of the world embroidered on silk. Look closely at the borders of the United Sates or Australia labeled as New Holland. These girls were interested in the entire world. Another global view is a small, fragile, gray silk embroidered sphere meant to be held – one of only 38 embroidered American globes which have survived over two hundred years.

Detailed family records are a very common subject of samplers. Peters explained the fascinating history of an uncommon, sampler made by a free African American girl in Maine whose parents, Francis and Mehitable Heuston, were “conductors” in the Underground Railroad. This sampler is complemented with a photograph of the Heuston’s family burying ground and a map of the underground railroad routes. Samplers could be political like the naïve one of a dancing couple embroidered on a pot holder, “Any holder but A Slaveholder,” sewn before the Civil War by abolitionists. A reproduction of a poster from an 1857 Anti-Slavery Fair puts the sampler in historical context. These fairs were held all over the northeast and Ohio and raised money to support the abolitionist cause and help free enslaved people.

Detailed family records are a very common subject of samplers. Peters explained the fascinating history of an uncommon, sampler made by a free African American girl in Maine whose parents, Francis and Mehitable Heuston, were “conductors” in the Underground Railroad. This sampler is complemented with a photograph of the Heuston’s family burying ground and a map of the underground railroad routes. Samplers could be political like the naïve one of a dancing couple embroidered on a pot holder, “Any holder but A Slaveholder,” sewn before the Civil War by abolitionists. A reproduction of a poster from an 1857 Anti-Slavery Fair puts the sampler in historical context. These fairs were held all over the northeast and Ohio and raised money to support the abolitionist cause and help free enslaved people.

National events like the death of George Washington were memorialized in complex compositions probably copied from artworks. Historic buildings, homes, and everyday life were also featured edged by decorative borders. Peters pointed out the missing letter J from many samplers. The first samplers used the early classical Latin alphabet with only 23 letters and the letter J did not appear until the late 1700s.

What is the most valuable kind of sampler?

Any sampler pictured in the two volume Girlhood Embroidery published in 1993 will bring a very high price. Betty Ring, the author, was the sampler expert and built a definitive collection of 18th and 19th century schoolgirl needlework. In January 2012, one New Jersey 1807 sampler sold for over a million dollars in a Sotheby’s auction of Ring’s collection. Generally, samplers done by a girl with a well-known teacher bring very high prices. Like any other antique, the history of ownership, the provenance, the condition, size, and the historic importance also contribute to value. The design, originality, and information are also key factors. American samplers are more valuable than English versions because there are fewer of them and they are far more inventive – in comparison the English versions often seem a little boring.

Why were samplers made?

Samplers demonstrated the needle craft and educational accomplishments of young girls. Typically, samplers were done at girls’ schools where they learned reading, writing, arithmetic, geography, and the critical skill of sewing. The maker’s name, place and date are usually included – they were important members of the family. Samplers were meant to be displayed, which explains why so many have survived as family treasures.

Some examples inventoried darning stitches used to repair clothing like Kezia Burrough’s 1807 sampler done at Westtown School (then spelled “Weston”). Remember that when samplers were made people did not have a closet full of clothes. Instead of throwing torn or worn clothing away, garments were repaired by the women of the house. The arrival of the Industrial Revolution with sewing machines, less expensive factory-made fabric and ready-made clothing contributed to the decline of samplers just before the Civil War.

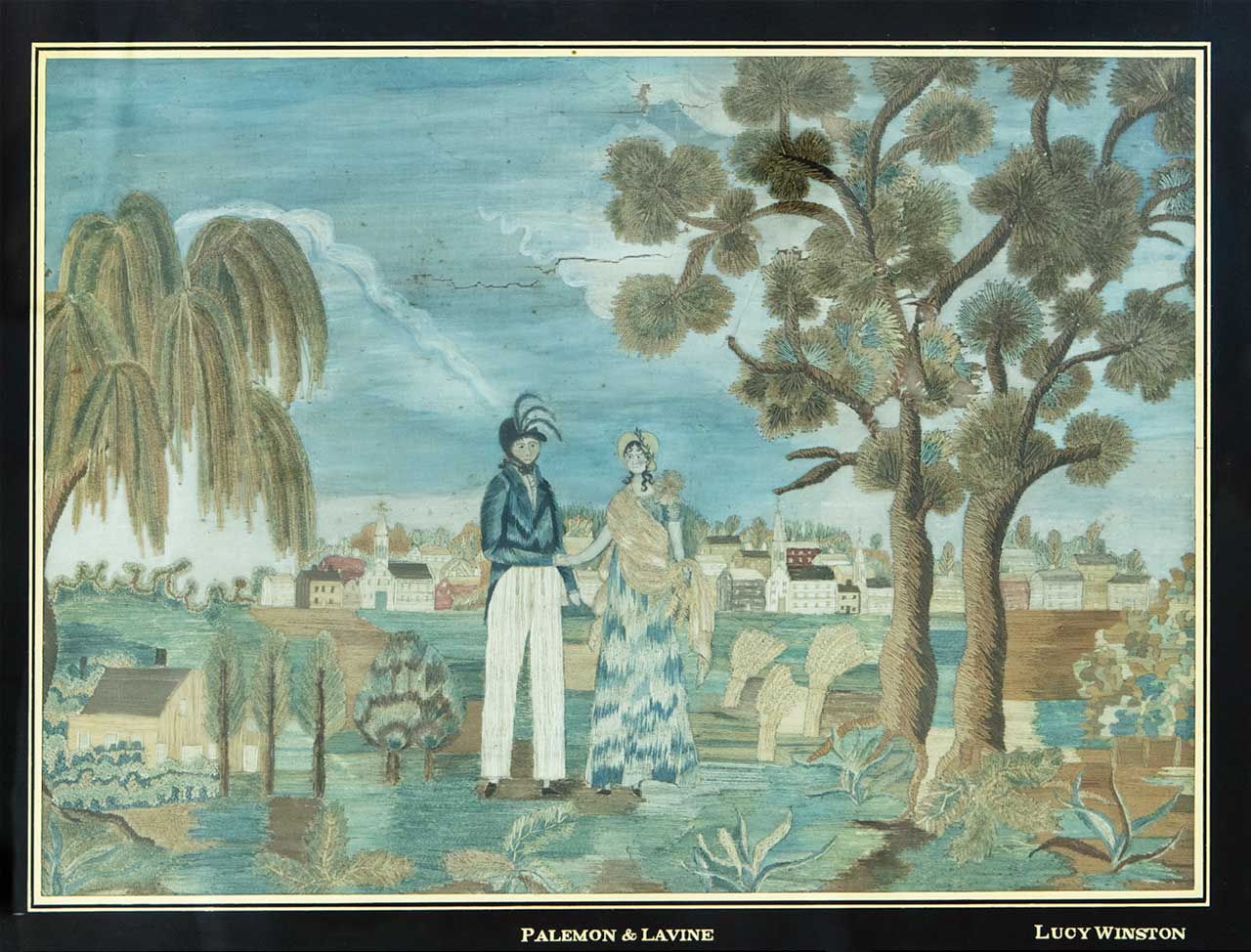

Samplers are not just stitching examples and the alphabet. They include geography, buildings, people, elaborate landscapes, complete family records and genealogy, and popular romantic themes like Palemon and Lavine (see photo to the right).

In New England many samplers were made at Quaker boarding schools because of the value the Friends placed on education and the equality of the sexes. Curving leaf and vine motifs are one indication of a Quaker sampler. I’m not quite sure why but there are very few surviving samplers from the south.

How did you become a collector of samplers?

I had aIways wondered about why we didn’t hear much about girls in history and their accomplishments and became fascinated when I first discovered an English sampler at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. A curator let me look at storage drawers filled with samplers – they don’t do that anymore. Over the last 25 years I have gradually researched and acquired over 120 samplers. I love investigating each one because of the hidden stories I have uncovered and can get lost discovering the makers and their time. Samplers are the only thing I collect – I try to avoid too much stuff. I purchased my first sampler just because I liked it – maybe it picked me. Then I started researching the girl who sewed the sampler, and her history came alive. This was a personal, tactile connection with women from another century. We had just purchased a 1794 house in Sharon and samplers belonged there – they were made to be displayed with pride. Samplers are a record of the lives and legacy of women and girls – they talk to us from the past and I am shepherding them into the future.

Where do you find them?

There are established reputable, knowledgeable dealers like Amy Finkel in Philadelphia and Carol and Stephen Huber of Old Saybrook, CT. Their websites are filled with information about samplers. Then there are auctions, antique dealers, and online sellers. Now that I’m knowledgeable I buy many online. The internet has made it so much easier to research everything.

Are there other exhibitions of samplers?

In 2018 there was a show at the National Museum of Scotland featuring samplers from the enormous collection of an American, Leslie Durst, who has one of the largest private collections of Scottish samplers in the world. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York had a show of American and European samplers in 2015 and there have been small, regional shows in museums but nothing recent. Over a hundred people came to the opening of the show in Sharon – and it’s attracting new visitors every day to the Historical Society. There’s definitely a curiosity and an interest.

Are there any fakes? How do you know?

There are fake samplers made to look old, but they don’t pass the “smell” test. Old things smell funny. The fabric itself is an indicator as well as the fading which should not be uniform. The textile should be brown around the edges not blotchy. After a while you just intuitively know.

How do you keep track of your collection?

I keep a file for every sampler and each girl. At first, I didn’t capture all the right information but now I know how to organize the collection and include my detective work and a paragraph or two about each sampler. With this information it was easy for me to create the educational labels for the show.

How do you preserve samplers? How do you clean them?

Unframed samplers should be placed in a box that has been lined with acid-free, lignin-free, buffered tissue that can then be folded over it. Never ever wash or press an old sampler. You might find suggestions online to wash with a “non-ionic” detergent – please ignore. Do not do this. I use the Textile Conservation Workshop to clean and restore my samplers, because they are highly trained professionals who know how to conserve textiles.

Are you still adding to your collection?

I am carefully adding to the collection, talking to dealers, watching at auctions and looking online. Once I buy, I never sell.