Local History

From Solstice to Santa Claus: How Christmas Became Christmas

-by the Hillsdale Historians

December 21 is the Winter Solstice, the longest day of the year and a holiday observed since the late Neolithic and Bronze Age. The Winter Solstice was immensely important in agrarian societies. In December, farmers enjoyed a period of leisure. The harvest had been gathered, the deep freeze of midwinter had not yet set it, and most cattle were slaughtered so they would not have to be fed during the winter. It was almost the only time of year when a plentiful supply of fresh meat was available. The majority of wine and beer made during the year was finally fermented and ready for drinking. It was a time to let off steam, and to gorge.

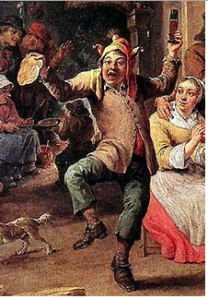

Although the Bible nowhere mentions the date or even the season of Christ’s birth, Solstice celebrations were so entrenched that early Christians opted to celebrate the Nativity at the same time, in the hope of attracting converts. Celebrating, lubricated by alcohol, could easily become rowdy trouble-making and in medieval and early modern Europe Christmas was a season of “misrule,” a time of raucous excess, flouting norms, aggressive begging and home invasions of the well-to-do by the poor. Celebrants often elected a “Lord of Misrule” to preside over these annual revels. In 1637 England, a crowd gave the Lord of Misrule a wife in a public marriage service conducted by a fellow reveler posing as a minister. The affair was consummated on the spot!

How this celebration of excess evolved into the domestic, family-centered tradition we know today is an interesting story of how a bawdy bacchanalia was tamed by 19th century Victorians.

In The Battle for Christmas (1996, Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.), Stephen Nissenbaum writes that during much of America’s 400-year history, Christmas was observed as a holiday of misrule, a time of raucous excess. God-fearing New England Puritans set about trying to suppress this wickedness, declaring celebrating Christmas to be a crime in 1659 and “purifying” 17th century New England almanacs of any mention of the holiday.

The Lord of Misrule

But despite the Puritans’ best efforts, Christmas in America became a drunken street carnival, a raucous combination of Halloween, New Year’s Eve, and Mardi Gras. In New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore and other cities, the poorest residents (mostly, but not exclusively, men and boys) drank to excess, fired muskets wildly, and engaged in “mumming,” costuming themselves in animal pelts or women’s clothes. Local bars actually serviced drinks gratis on Christmas Day, a holdover from an old English custom. The poor would demand entrance into the homes of the well-off and aggressively beg for food, drink, and money. Celebrants formed Callithumpian parades, disturbing the peace by beating on kettles, blowing on penny trumpets and tin horns, and setting off firecrackers.

Sometimes things would escalate and there would be break-ins, vandalism, and sexual assault. In 1828, a particularly violent Christmas riot in New York led the city to create its first professional police force.

We could find no records suggesting that Christmas was observed this way in Hillsdale in the 18th century. Possibly the Yankee New Englanders who founded the tiny squatter settlement of Nobletown (today’s North Hillsdale) were too busy feuding over land claims with the powerful Van Rensselaers to the north, who constantly threatened the hill town settlers along the Massachusetts border. In 1766 the Van Rensselaers hired British troops to evict the Nobletown settlers and burn the settlement to the ground.

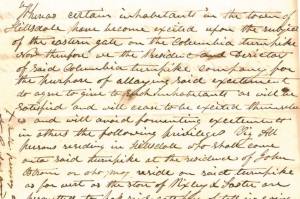

But there are hints that after the Revolutionary War Hillsdale residents remained an unruly bunch. In 1799 the Columbia Turnpike Directors had to draft a “Hillsdale Exception” permitting gate hopping by Hillsdale residents at the East Gate Toll House: “Whereas certain inhabitants in the town of Hillsdale have become excited upon the subject of the eastern gate on the Columbia Turnpike … for the purpose of allaying said excitement [we] do agree to give to such inhabitants as will be satisfied and will cease to be excited themselves and will avoid fomenting excitement in others the following privileges …” In other words, everyone should just calm the hell down.

In larger communities, late 18th century seasonal celebrations were male rituals that excluded women and families. At the end of 1784 Theodore Sedgwick of Stockbridge wrote a jocular letter to Henry Van Schaack of Claverack calling him a “drinking devil” and promising that when the two met they would “eat & drink & be merry.” It wasn’t until the mid-1810’s that the Sedgwick children began to wish one another a merry Christmas and a happy New Year.

The Hillsdale Exception

In the early 19th century, the Industrial Revolution overtook the agrarian economy and there was no longer a lull in the demand for labor: employers insisted on business as usual all year long (think Ebenezer Scrooge). As farmers moved to towns and cities in search of work, the appearance of an economic underclass brought an explosion of poverty, vagrancy, homelessness and public violence. In the eyes of “respectable” citizens, cities “appeared to have succumbed to disorder … and seemed to be coming apart completely.” Christmas misrule had become such an acute social threat that respectable residents could no longer ignore it or take it lightly. Something had to be done.

A handful of wealthy, politically conservative New Yorkers was primarily responsible for creating a new kind of a Christmas. In 1809 Washington Irving, who had long lamented the absence of distinctively American holidays, published the satirical Knickerbocker’s History of New York in the guise of a “history of New Amsterdam” during old Dutch times, and forged a pseudo-Dutch identity for New York that became a cultural counterweight to the “misrule” of the early 19th century city. Writing as “Diedrich Knickerbocker,” Irving described fictional St. Nicholas Day celebrations where “Santa Claus” (an Americanization of the Dutch Sinterklaas, or St. Nicholas) would distribute gifts to children. These celebrations were wholly invented, but the book was read by many as serious history and became a best seller, not only in the drawing rooms of New York City but in log cabins on the frontier.

Fourteen years later Clement Clarke Moore, a prominent Protestant theologian (and slave owner) became famous for a 56-line poem written solely to amuse his children. Moore described St. Nicholas as a jolly miniature elf with a sleigh full of toys and eight flying reindeer. He set St. Nicholas’s visit on December 24, not December 5, the eve of St. Nicholas’ day, and mixed a number of European legends together: the gift giving of the Dutch St. Nicholas, the Norse god Thor’s sleigh pulled by flying goats, the chimney descent of “house spirits” in Germany, and the French and Italian practice of hanging stockings. A Visit from St. Nicholas was first published (anonymously) in the Troy (NY) Sentinel in 1823.

Thomas Nast’s vision of Santa Claus, 1881

But it was political cartoonist Thomas Nast, the terror of Tammany Hall and creator of the Republican elephant and the Democratic donkey, who developed the visual image of Santa Claus. Nast gave Santa his familiar shape: fat and jolly, with a stocking cap and a long white beard. Nast’s first Santa Claus appeared during the Civil War in 1863 as a morale booster for Union soldiers.

Over the course of the 19th century, the rude revelry of Christmas misrule was gradually channeled towards domestic felicity. The rowdy Christmas season did not simply disappear: to read newspapers in mid-century is to see upbeat editorials about Christmas shopping and the joyous expectations of children juxtaposed with unsettling reports of holiday drunkenness and rioting. But newspapers began to relegate coverage of revelry and riots to the police column. Celebration moved from the street to the parlor. The temperance movement, spearheaded by women, promoted sobriety and pushed coffee as a substitute for alcohol during the holidays. Merchants began turning their stores into holiday emporiums full of tempting toys and gifts. Christmas was declared a federal holiday in 1870. In 1913, Hillsdale’s own Freeman Pulver promised a “Grand Display of Holiday Goods” … “The most extensive line in town.”

In 1931 the Coca Cola Company debuted the Santa Claus image that persists today. Originally a marketing gimmick to get people to drink Coke year-round instead of just during the summer, the campaign was so successful that Coke ran it until the 1960s.

All of this is to say that the modern family Christmas is not a timeless tradition. It was invented less than 200 years ago, largely to prevent an impoverished underclass from upsetting the social order ushered in by market capitalism.

There are still some modern holiday observances that retain an early anarchic spirit. SantaCon, the annual pub crawl, started as “joyful performance art” in San Francisco but has devolved to a “reviled bar crawl” of drunken brawling, vandalism, neighborhood terrorization, public urination and disorder, especially in New York City where it has resulted in fierce community resistance. The 2017 SantaCon in Hoboken NJ resulted in 17 arrests and 55 hospitalizations.

For most Americans, the holidays of 2020 will be a quiet affair, more like Victorian family-centered celebrations than the pagan-inspired revels of the country’s early years. Perhaps we will use this fallow time to create our own holiday traditions, ones that value connection over commercialism, and giving over getting.

In whatever way you celebrate the end of year, the Hillsdale Historians wish you peace, prosperity and good health.

Follow the Hillsdale Historians and see their latest blog posts as well as past stories by signing up here