Local History

Litchfield County’s Railroads

Connecticut, long known as the Land of Steady Habits, came late to the railroad craze that swept the country in the 19th century. In fact, neighboring states had to prompt Connecticut into its first railroad ventures. When completed, however, these lines provided both a much more efficient means for the industrial and agricultural products of Litchfield County to reach national markets and a new way of travel for county residents.

The first locomotive-powered railroads in the United States appeared in the mid-1820s. Within ten years, plans were in the works to bring railroads to Litchfield County. At the peak, the county was serviced by four railroad lines: the Housatonic, which connected Bridgeport and the Massachusetts border and ran roughly parallel to today’s Route 7; the Connecticut Western, which connected Hartford to Poughkeepsie, the Naugatuck, which connected Devon on the Long Island Sound with Winsted, with a separate spur allowing access between Waterbury and Watertown; and the Shepaug, which ran from Hawleyville to Litchfield. In addition, Terryville had a station on the New York and New England Railroad.

Construction costs for these railroads were high but were deemed necessary for creating an infrastructure that would allow the region to remain economically viable. Expenses for building railroads lines in Connecticut ranged from $16,000 to $43,000 per mile. None of this money came directly from the state government, as the legislature had banned public aid for building railroads. However, the legislature did allow municipalities to purchase stock in railroad companies. Dividends would be tax-free for a period of time. Individual towns, which stood to greatly benefit from inclusion on a railroad line, were often the most eager to purchase stock or loan money to the railroad companies.

The Housatonic Railroad

The Housatonic Railroad was chartered in 1836 and in their haste to complete it, its promoters “threw caution to the wind,” the result being that sound construction practices were “ignored or at best overlooked.” An 1854 report by the state railroad commission found that “station houses and buildings on the line are of cheap construction.” Part of this was due to financial difficulties, as construction began in 1837, the year of a nationwide economic panic. The city of Bridgeport issued bonds to fund the railroad, then defaulted and the state refused to intervene.

Still, progress on the “Ousatonic,” as it was identified in its application for a charter, continued and the line opened between Bridgeport and New Milford in February 1840, with a band playing on board a railroad car bedecked with banners and flags. One newspaper reported that the train was “welcomed by several acres of people” and that “church bells were rung with much earnestness and the old cannon located on the rocks below the village poured forth its thunder of welcome to the railroad screaming steam whistle.” The celebrations were merited; Litchfield County, long subject to isolation, was establishing regular contact with the outside world.

By 1842, all 74 miles of track between Bridgeport and Canaan were complete. In 1850, the Housatonic connected with the Western Railroad of Massachusetts, which provided service to both Albany and Boston. In fact, it was the Housatonic that first established a rail connection between New York City and Albany. That same year Alexander H. Holley of Salisbury, a railroad promoter, reported that between 150 and 200 passengers utilized the Housatonic every day, in addition to iron, granite, and large quantities of milk. The Housatonic, with its fire-burning engines, had regularly scheduled milk trains, equipped with hundreds of 40-gallon containers in cars specifically designed for transporting milk. In 1850, the railroad reported $126,989 in revenue from transporting passengers, and $170,081 from freight. By 1890, these numbers had increased to $529,854 and $796,368 respectively.

A passenger run from New Milford to Canaan took one hour and eleven minutes, while a train carrying a mixture of passengers, freight and milk took up to four hours, forty six minutes to make the same run. Within Litchfield County there were stations at Still River, New Milford, Boardman’s Bridge, Gaylordsville (Merwinsville), South Kent, Kent, North Kent (Flanders), Cornwall Bridge, West Cornwall, Lime Rock, Falls Village, Pine Grove, and Canaan.

The New Milford station, constructed in 1886 at a cost of $15,000 survived the fire of 1902, welcomed President Theodore Roosevelt the same year, and still stands today, although the shack next to the station that controlled the gate is gone. The Boardman Bridge station was heavily utilized by teachers and students. The Pine Grove station in Canaan facilitated travel to the nearby Methodist retreat camp.

It was the Merwinsville station in what is now the Gaylordsville section of New Milford, however, that best epitomizes the opportunities brought by the railroad. Sylvanus Merwin owned a hotel in the area when the railroad was being laid out in 1837. Learning of the proposed route, he agreed to sell land to the railroad in exchange for his hotel being a designated meal stop on runs between Pittsfield and Bridgeport, and that he be named the agent for the ticket office that would be located inside the hotel. Merwin prospered until 1877 when a dining car was added to the train. Following Merwin’s death in 1884, his son-in-law Ed Hurd ran the hotel for summer visitors and for dances but eventually was forced to close the hotel. He remained ticket agent, however, until the railroad decided to replace Hurd, which necessitated closing the office and establishing a new one; the area was renamed Gaylordsville.

The Central New England Railroad

The other major railroad of northwest Connecticut was the Central New England Railroad, originally called the Connecticut Western. This was the dream of Egbert Butler of Norfolk who worried that his hometown would be isolated with no possibility of economic growth without a railroad. He paid for a survey himself and secured influential promoters including Alexander Holley and W. H. Barnum of Salisbury and William Gilbert of Winsted.

Construction began in 1869, and despite the difficulties of crossing the mountains from east to west, the line was completed in 1871. Included on the route was a stop at Norfolk Summit. At 1,333 above sea level it was one of the highest stations in the East. The line went bankrupt in 1880, and spent much of the rest of its tenure in financial difficulty or reorganization.

Still, the railroad provided an important means of moving goods across the state and to New York. It also helped promote Norfolk and Salisbury as summer residences. Mothers and children often spent summers on Twin Lakes while fathers would visit on weekends. Boats met them at the station and took them across the lake.

In Canaan, the Central New England and the Housatonic railroads intersected. The station there was “furnished with every convenience and … in the most modern style.” It was topped by a weather vane shaped as a steam locomotive, which was created by workers at the Amesville repair shop and given to the town. The station was most notable, however, for the pies served in its restaurant. These were the work of Ada Nicoll, who was famous for her apple, rhubarb, lemon meringue, and pumpkin varieties.

The Shepaug Railroad

Few enterprises better exemplify both the high hopes and deep fears people had for railroads in the 19th century than the Shepaug Railroad. The line was surveyed by Edwin McNeil in the 1860s, despite threats put forth by armed farmers. Construction began in 1870 with one crew starting in Litchfield and another in Hawleyville. The route was noted for being particularly winding, as it ventured around mountains and rivers. In one stretch, the presence of between 150 and 200 curves necessitated 32 miles of track to cover 17 miles as the crow flies. It also required a 235 foot-long tunnel in what is now Steep Rock Preserve in Washington Depot.

A passenger train that left Litchfield at 6:25am reached Hawleyville at 8:00am, where a connecting train could take the rider to New York City, reaching Grand Central Station at 10:33am. The line also transported iron, granite, manufactured goods, and ice from the county’s ice houses. Particularly notable was the Echo Farm operation on Chestnut Hill in Litchfield, the first in the country to bottle milk for distribution by train. The line went bankrupt twice in its first fifteen years, was merged with the New York, New Haven and Hartford in 1898 (all the states railroads were eventually part of this line, known as “the Consolidated”), and ceased operations in 1948.

Accidents and tragedy

If railroads brought opportunity to the county, they also brought tragedy. In 1911, nineteen were injured when a train jumped the track one mile south of Washington. In 1913, a milk car rammed a passenger car in Canaan; 86-year old Mrs. Frank Olin was killed in the crash. Mrs. N. H. Blake of Cornwall Bridge was holding a one-year old at the time of the collision. The baby was thrown from her arms, but was caught by F. C. Sprague.

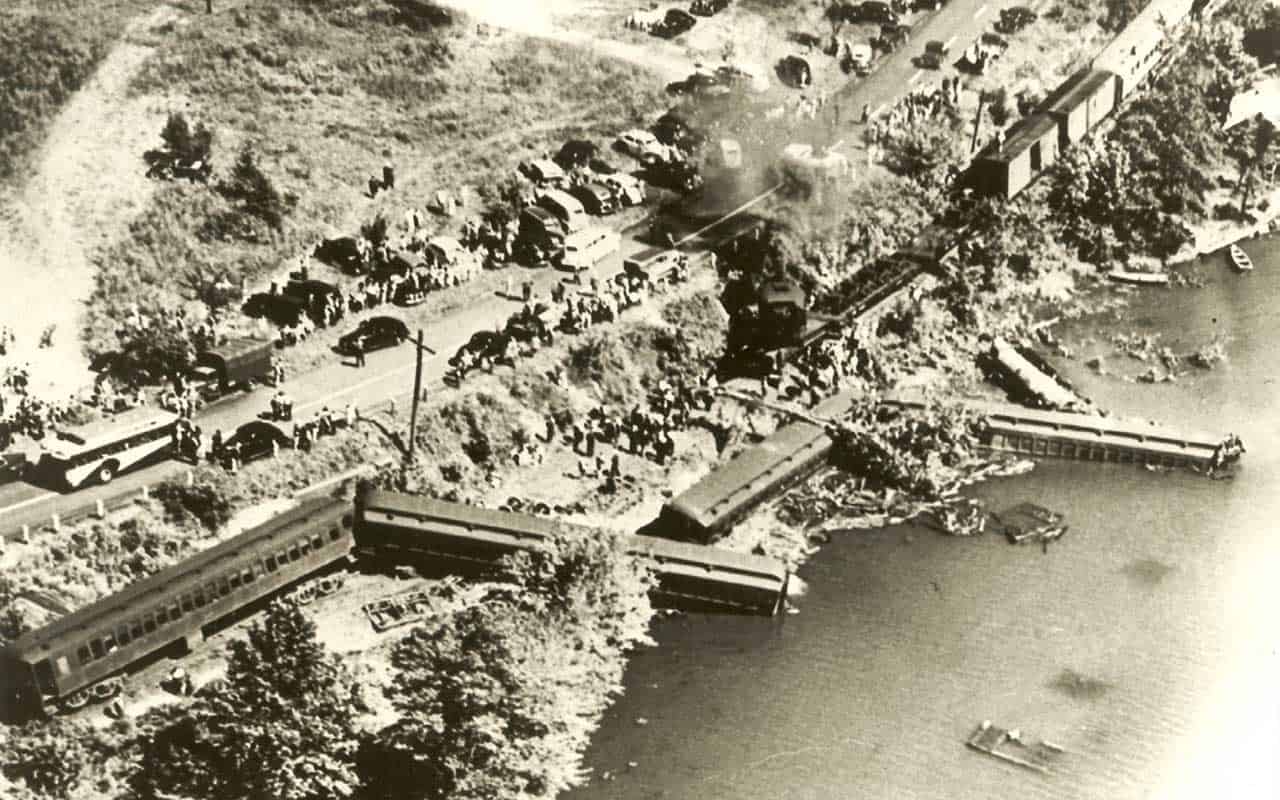

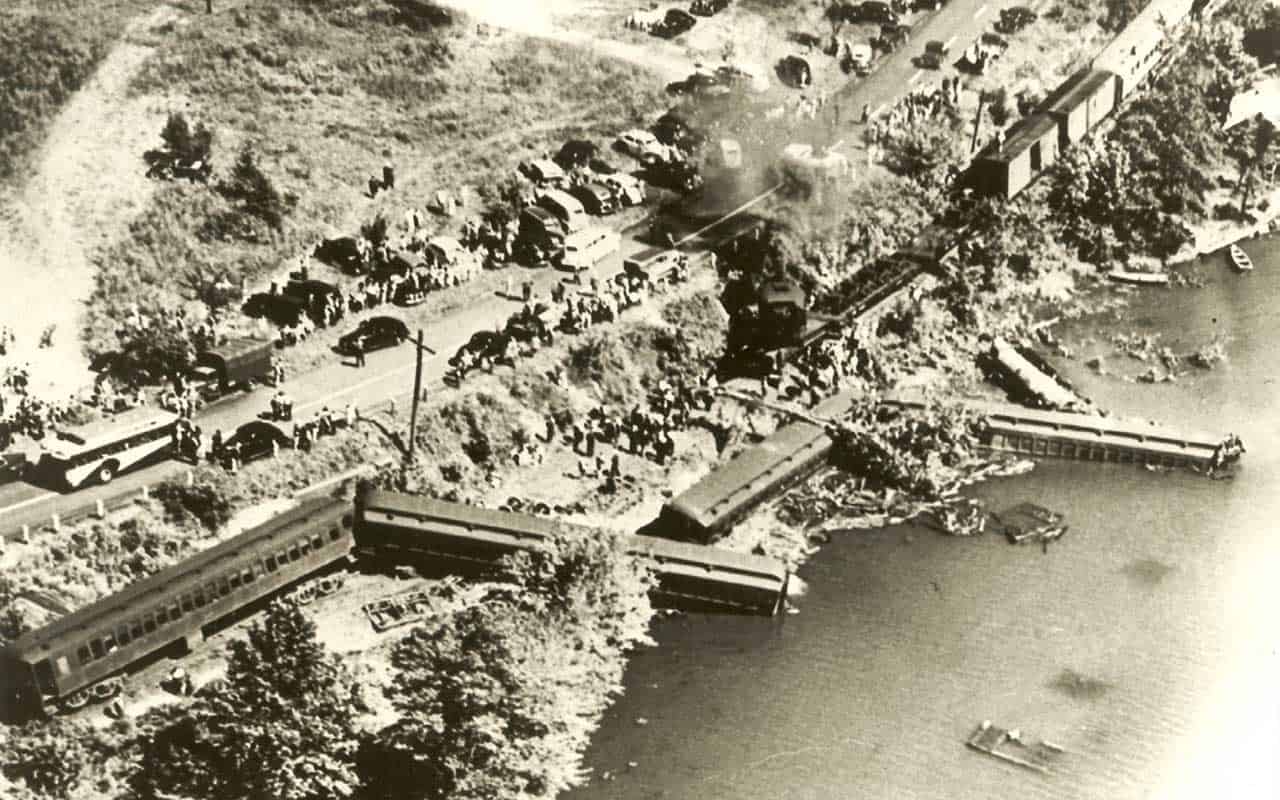

Perhaps the most notable railroad accident in the county took place along the Housatonic tracks in South Kent. On August 28, 1941, a six-car train with 254 young campers returning to New York City from the Berkshires aboard derailed along Hatch Pond. Two engineers – Theron Dixon of Danbury and Harold McDermott of West Stockbridge – were killed instantly. Otto Klug of Seymour, the train’s fireman, was pinned beneath a car, trapped in five feet of water. Children held his head above water while an improvised halter was constructed. Doctors arrived from Danbury and amputated Klug’s leg, releasing him from under the car. The accident could have been far worse except that it was lunchtime and most of the children had gone to the dining car, one of the two cars not to derail.

Except for occasional freight trains, the days of rail service in Litchfield County have passed. An observant eye, however, will notice that the berms remain, now devoid of tracks. Particularly good examples can be seen as one drives toward Norfolk on Route 272. These offer testimony to an earlier age when the region’s industrial goods rode the rails to the outside world. •