This Month’s Featured Article

Local Legacy

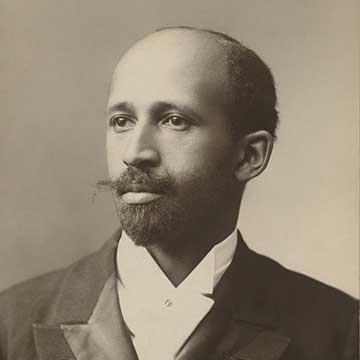

Since the October issue celebrates the area’s rich history, it proved to be an opportune time to honor the achievements of William Edward Burghardt Du Bois. Renowned as W.E.B. Du Bois, he was a scholar, sociologist, historian, activist, and journalist.

Since the October issue celebrates the area’s rich history, it proved to be an opportune time to honor the achievements of William Edward Burghardt Du Bois. Renowned as W.E.B. Du Bois, he was a scholar, sociologist, historian, activist, and journalist.

The Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield, MA, features a permanent exhibition that highlights some of his life’s work. Visit The Feigenbaum Hall of Innovation, an interactive exhibition that celebrates innovators like Du Bois who hail from the Berkshires. Here’s a history and a few highlights of his legacy.

A history

Great Barrington, MA, is the hometown of Du Bois who was born on February 23, 1868. Growing up, he spent time in the company of many intellectuals and was inspired to learn.

After graduating from Searles High School where he served as valedictorian in 1884, Du Bois attended Fisk University – a historically Black college in Nashville, TN. Donations from church members at the Congregational Church in Great Barrington funded his tuition.

Although Du Bois witnessed racism during his childhood in the Berkshires, this didn’t fully prepare him for the South with its Jim Crow laws, Black voting suppression, lynchings, and beyond. While studying at Fisk University, Du Bois spent his summers teaching in Tennessee. This gave him personal insight into the poverty and discrimination that young Blacks endured. In 1888, he earned his Bachelor’s degree.

In fall of 1888, Du Bois began his studies at Harvard, which failed to honor his degree from Fisk because it was considered inferior. After entering Harvard as a junior, Du Bois graduated with his second Bachelor’s degree in 1890. History was his area of study.

Du Bois completed his graduate work at Harvard University in 1895 and was the first African American to receive a PhD. His doctoral thesis, “The Suppression of the African Slave Trade to the United States of America, 1638–1870,” became his first book.

From 1892-1894, Du Bois studied at Humboldt-Universitat zu Berlin (then the University of Berlin). His studies with German economists, sociologists, and historians was very influential and shaped his perspective.

According to Berlin Days, 1892 -1894: W. E. B. Du Bois and German Political Economy by Kenneth D. Barkin (Duke University Press), “Throughout his life, indeed, Du Bois stressed the importance of his ‘Berlin Days’ on his subsequent intellectual development. In My Evolving Program for Negro Freedom, an essay he wrote in 1944 for Rayford Logan’s What the Negro Wants, Du Bois was quite clear about the importance of the year 1910, when he abandoned the Germans Gustav Schmoller and Max Weber (although I believe he meant Adolf Wagner rather than Weber) in favor of his Harvard professors William James and Josiah Royce. The implications of his essay have been missed by many Du Bois scholars; there is much evidence that his professors in Berlin were critical contributors to the strategy he embraced to mitigate racism in the United States for at least a decade, from his return in 1894 until 1910. Du Bois’s thoughts had turned to Germany long before he enrolled at the University of Berlin. He had studied the German language for three years at Fisk University in Nashville, TN, and delivered his valedictory address in 1888 on Otto von Bismarck.”

Sociology

Du Bois was broadly trained in the social sciences. Although he later shifted his mindset, Du Bois initially believed that social science could provide the knowledge needed to solve race problems. For more than a decade, he devoted himself to sociological investigations of Blacks in America. He produced 16 research monographs, which were published between 1897 and 1914 at Georgia’s Atlanta University, where he was a professor.

As an assistant instructor at the University of Pennsylvania, Du Bois conducted a study of the socioeconomic issues endured by Philadelphia’s Black

According to Penn Today – a University of Pennsylvania news source, “Du Bois was not offered a professorship at Penn after his position expired. He was hired as a professor at Atlanta University – now Clark Atlanta University – where he founded the field of modern sociology. In 1903, he published his masterful The Souls of Black Folk, and became one of the most famous African Americans in the country.” He continued his work at Atlanta University.

Activism

While pursuing his studies, Du Bois was a voice for civil rights and activism. He was also a peace activist and later an advocated for nuclear disarmament.

In 1905, he formed the Niagara Movement – an organization of Black scholars and professionals who were dedicated to social justice. The group met in Erie, Ontario, near Niagara Falls.

In 1909, he co-founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). It strived to secure for all people the civil rights guaranteed in the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the United States Constitution. Its national office was established in New York City in 1910. Despite its commitment to multiracial membership, Du Bois was the only African American among the organization’s original executives. He was appointed director of publications and research. In 1910, he established The Crisis.

By 1913, NAACP established branch offices in Boston, Baltimore, Kansas City, St. Louis, Washington, DC, and Detroit. Membership swelled from approximately 9,000 in 1917 to about 90,000 in 1919.

Until 1934, Du Bois remained a leading figure in the NAACP. He later determined he could no longer support its goal of racial integration. Disappointed in the lack of progress towards equality, he began advocating for Black separatism.

Du Bois returned briefly to the NAACP from 1944 to 1948, when he served as director of special research. He prepared and presented the grievances of Black Americans before the newly established United Nations. In his 1947 report, An Appeal to the World: A Statement on the Denial of Human Rights to Minorities in the Case of Citizens of the United States of America and an Appeal to the United Nations for Redress,” the NAACP asked the United Nations to redress human rights violations that the United States committed against its African-American citizens.

Throughout the 1940s, the NAACP saw enormous growth. By 1946, there were 600,000 members. It provided legal representation and aid to members of other protest groups. The NAACP posted bail for hundreds of Freedom Riders in the ‘60s who had traveled to Mississippi to register black voters and challenge Jim Crow policies.

End of life

Du Bois believed that capitalism contributed to racism, and was generally sympathetic to socialist causes throughout his life. According to the W.E.B. Du Bois National Historic Homesite, his ideas were threatening to some, and in the 1950s during the McCarthy era, he was falsely accused of being an agent of a foreign power and later exonerated of all charges.

At the invitation of Ghana’s President Nkrumah, Du Bois moved to Ghana at the age of 93 to undertake writing the Encyclopedia Africana – a collection of the achievements of people of African descent. Du Bois passed away in Ghana in 1963, having never completed it.

His passing occurred on the eve of the historic Civil Rights March on Washington, at which Roy Wilkins, then leader of the NAACP, proclaimed to the 250,000 people gathered at the Lincoln Memorial: “At the dawn of the 20th century his was the voice that was calling to you to gather here today in this cause.”

W.E.B. Du Bois Homesite – A National Historic Landmark

History buffs can visit the W.E.B. Du Bois National Historic Site in Great Barrington. The National Historic Site program is comprised of numerous places that were relevant to Du Bois as a young man, and includes the Du Bois Homesite, a National Historic Landmark under the stewardship of UMass Amherst.

These sites are all part of the Upper Housatonic Valley African American Heritage Trail, an extensive interpretive program which encompasses 29 towns in Massachusetts and Connecticut. It celebrates African Americans in the region who played pivotal roles in key national and international events, as well as ordinary people of achievement.

The W.E.B. Homesite is open daily from dawn to dusk for self-guided tours. The Homesite features a level woodland path with a number of interpretive panels that provide information about Du Bois and the Homesite. It is important to note that the house no longer exists, but visitors will find this serene setting to be quite inspirational.

Put your walking shoes on. There’s a Du Bois Walking Tour of Downtown Great Barrington. It has about 20 locations. Among them are River Park, his birthplace, the Great Barrington Schools, and beyond.

W.E.B. Du Bois Homesite – A National Historic Landmark. 612 S. Egremont Rd., Great Barrington, MA. Call (413) 717-6359 or visit online at duboisnhs.org and africanamericantrail.org