This Month’s Featured Article

ROADS: GOING FROM HERE TO THERE

It’s a phenomenon most have encountered. The first light snowfall of the winter season fails to accumulate on our modern roadways, but the perceptive driver notes a white dusting that outlines an ancient roadbed in the adjoining woods. Nor is this the only extant vestige of a prior century’s transportation system. Mile markers stand as stone monoliths on the outskirts of towns, while hitching posts and carriage steps are still found around village greens.

It’s a phenomenon most have encountered. The first light snowfall of the winter season fails to accumulate on our modern roadways, but the perceptive driver notes a white dusting that outlines an ancient roadbed in the adjoining woods. Nor is this the only extant vestige of a prior century’s transportation system. Mile markers stand as stone monoliths on the outskirts of towns, while hitching posts and carriage steps are still found around village greens.

Roads, then and now

The presence of these artifacts should not be surprising. In 2019-20, the State of Connecticut will spend more money on transportation than on any other item in its budget. It was no different in earlier times. In fact, the remoteness of colonial Litchfield County led its residents to place a premium on establishing and maintaining roadways that would provide connections to the outside world, allowing for the exchange of news and goods and services. Thus it was that at the first town meeting in the newly-established hamlet of Cornwall a vote was taken to build roads, at tremendous cost, to Kent and Litchfield, with the townspeople further specifying that the road was to be at least six rods wide. But in a world where danger – in the form of the unknown – lurked behind every tree, this was a small price to pay for the peace of mind brought by a pathway to a neighboring town.

Much of Litchfield County’s current road network was in place by 1850 built upon Native American trails, roads built by towns in their earliest days, or late 18th or early 19th-century turnpikes. Our oldest roads are those that follow old Indian paths. Native Americans had less need for roads, as they did not – until the coming of Europeans – travel by horse or use large wagons or carts. The traditional Indian practice of burning underbrush to allow edible plants to grow also served to clear the forests for foot travel. The most popular routes became worn paths. Among these was the Paugusset Path, which connected the Berkshires with the Long Island Sound. We recognize it as Route 7 today.

These paths made travel for the groups of settlers pushing into the northwest hills extraordinarily difficult and slow. Historian G. H. Hollister described such a passage in 1858:

“Over mountains, through swamps, across rivers, fording or upon rafts, with the compass to point out their irregular way, slowly they moved westward; now in the open space of the forest, where the sun looked in; now under the shade of the old trees; now struggling through the entanglement of bushes and vines – driving their flocks and herds before them – the strong supporting the weak, the old caring for the young, with hearts cheerful as the month, slowly they moved on.”

Town ways and county roads

Braving these elements, the settlers made their way to their land claims, erected temporary shelters and began clearing land for farming and livestock. Then they turned their attention to roads. There were two basic types of roads in the Connecticut colony. The first were known as town ways and served an intra-town purpose. These could be private, running, for example, from a farmer’s home to his woodlot. They could also be public, connecting several farms to a grist mill. The second were county roads, which extended beyond the settled areas of a town and connected a town or settlement with a neighboring community.

In the county’s earliest days, little regard was given to future growth when laying out roads. Rather, they were built on an as-needed basis, and townspeople could appear before the selectmen to request a new road. When a new road was constructed through a farmer’s property, he was entitled to compensation and an appeal to the General Court of the Colony was possible for those who objected to the rate given by the town. And should the town reject the request by a farmer for a road to connect his fields to the rest of the town, that farmer could appeal to the General Assembly, which could force the town to build the road.

To call these pathways “roads” is to risk comparing them to modern thoroughfares. Rather, the earliest roads in the county were simply cleared swaths. Trees were felled, but stumps and boulders were left in the ground. There were few tools available to road crews beyond shovels, axes, and an iron disk that served as a primitive road grader. This was pulled by a team of four or six oxen, with men following behind shoveling dirt to the center in an attempt to cover obstacles and create a crown. This usually didn’t last long, as the more a road was used, the more likely the center was to become lower than the sides, creating what is often called a “sunken road.” Brooks and creeks often flowed through the roads, especially in the springtime.

To combat these impediments, roads were designed to be very wide. The roads of Litchfield illustrate this point. Middle Street, now known as Gallows Lane, was an amazing twenty-eight rods (462 feet) wide, providing plenty of space for travelers to transport their livestock or avoid the remaining stumps or boulders. In some places it is easy for 21st-century explorers to see the remnants of these old, significantly wider, roads. Along North and South Streets in Litchfield, for example, the hitching posts and carriage steps of the 18th and 19th centuries remain, set back considerable distances from the modern roads, but at the edge of earlier roadways.

The men who built the roads

As there were no sophisticated tools for road making, neither were there professional road crews. Ordinary townsfolk did the work. As early as 1638, well before any Litchfield County town was established, the Connecticut General Assembly mandated that all able-bodied men in town (later defined as men between 16 and 60) work for at least one day a year to “keep highways in use.” In 1650, the number of days worked on the roads was increased to two per male resident. However, not only was it possible to buy a substitute to work in one’s place, but the fines for failure to work on the roads were so small as to encourage men to neglect their duties. Some Litchfield County towns – Thomaston, for example – solved this problem by hiring their poor to work on the roads.

The worst roads in America

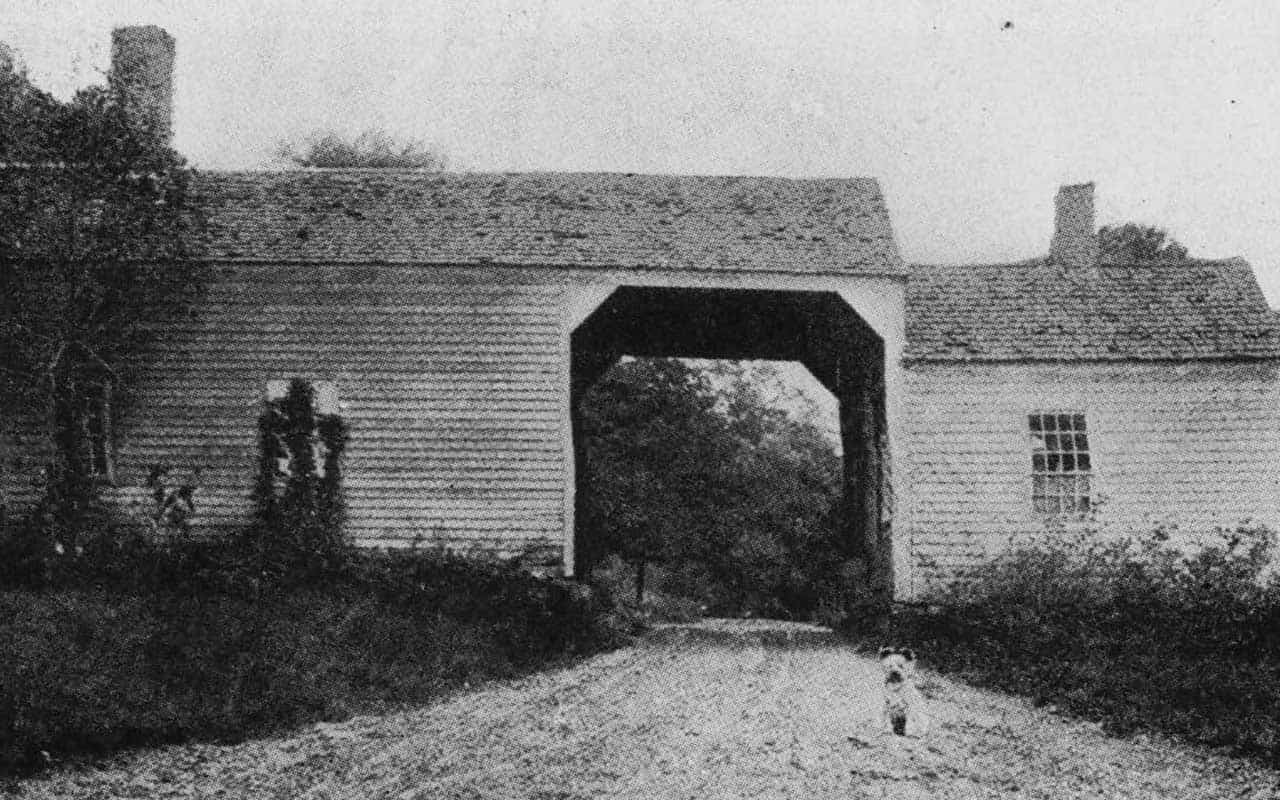

The number of stones, frequency of frost heaves and unpredictable weather, and the wear on the roads caused by the transportation of iron gave northwestern Connecticut’s thoroughfares a reputation as among the worst in the American colonies. Dr. Samuel Holten, who traveled from Boston to Philadelphia in June of 1778 reported that the roads between Hartford and Litchfield were “very bad,” but that those between Litchfield and the New York line were the “worst he ever saw.” Especially problematic for the small towns of Litchfield County were bridges, which were particularly expensive. To fund bridges, towns sought permission to hold lotteries, traded land for labor, and even, in some cases, granted the right to charge a toll in perpetuity to individuals who would build bridges. (This last scenario later proved to be a major headache for towns, which had to buy back those rights at high costs). And bridges had remarkably short shelf lives, lasting on average only seven to ten years. By covering a bridge, however, its lifespan could be doubled.

The Revolutionary War forced Connecticut to reorganize its transportation network, as it could no longer rely upon the British merchant fleet to transport its goods. New roadways were needed, but with the state in debt and unwilling – in the wake of the Revolution – to tax its residents for new roads, innovative thinking was required. The solution was a network of privately-built roads known as turnpikes. Between 1795 and 1853, 121 turnpikes were chartered in the state. Corporations, formed for the express purpose of building a roadway, would apply to the state for a charter. If the state agreed that there was a need for the proposed road, it would grant its approval, oversee the drafting of a route, and instruct the impacted towns to purchase the land. The turnpike company was responsible for constructing the road and any larger bridges; the towns were on the hook for smaller bridges. In exchange, the company was given the right to operate two tolls per road and collect up to a 12% return on its investment. (An additional type of early road, the shun pike, was commonly built to whisk travelers around these tolls). To guard against price gouging, if any company collected more, its road would revert to public control.

Many vestiges of the turnpike system remain. The companies – or even some individuals – often placed mile markers alongside the turnpike. Jedediah Strong of Litchfield placed one along the Litchfield-New Milford Turnpike (now Route 202) in 1787. It still stands in front of what is now Litchfield Bancorp. A notable mile marker stands along Route 6 in Woodbury, with a marker proclaiming it to be the “Benjamin Franklin Mile Stone.” (While there is no clear connection to the Founding Father, he was the nation’s first Postmaster General, and the roads certainly helped with mail service). Signposts were erected at the junction of two turnpikes to provide directions to travelers. Excellent examples remain in Harwinton and Milton.

The Straits- and Greenwoods Turnpikes

In the 1790s it was fashionable to construct turnpikes according to the French style of the time, which called for long, straight and wide roads, with as few turns as possible. These roads consequently encountered more steep grades and water crossings. The Straits Turnpike, which ran from New Haven to Canaan, is a good example of such a road. Drivers able to steal a quick glance will notice the amount of work road crews had to do to cross streams and ravines to construct a road that runs almost due north-northwest.

Still, width and straightness could only do so much to ease the difficulties of travel. More noteworthy is that there was not a major innovation in transportation between the time of Julius Caesar and George Washington, two thousand years later. While the stagecoach may have provided some style and luxury in the form of glass windows and leather seats, it did nothing to speed up the journey. A twenty-four mile stage ride from Litchfield to Sharon took fourteen hours. Horses needed to be changed every ten miles, a fact that led to the large number of taverns that dotted the turnpikes. All travelers were dependent upon their horses, a fact commemorated by the monument on Bentley Road in Harwinton, where the Catlin family used a spring-fed trough to establish an early rest area.

The Greenwoods Turnpike, which ran from New Hartford to Winsted to Norfolk before continuing on to the Massachusetts border, was one of the most successful turnpikes in state history. It was built between 1798 and 1799 at a cost of $19,500, or $815 per mile. The roadway paid dividends for seventy years. This, however, was an exception as over 80% of Connecticut’s turnpikes operated with little to no return on investment. When they failed, the roadways, per their charters, reverted to state control.

While Connecticut’s last private roadway ceased operations in 1897, these turnpikes, along with the old Native American trails and town roads, laid the foundation for the road system we know today. •