Local History

Swipe Right If You Like Professor Herman S. Johnson

– by the Hillsdale Historians

In last month’s post about Ida Haywood Pulver, we noted that Ida attended the Hillsdale Classical Institute. We were curious because we had not heard of this school and set out to learn more. What we learned about the school turned out to be less remarkable than what we discovered about its founder and principal, Professor Herman S. Johnson.

First, a little background on the Hillsdale Classical Institute. It opened in 1880, a time when most public education served students only through the eighth grade. Parents who wanted to extend their children’s studies through what we would today call “high school” had to rely on private, tuition-financed institutions. In 1879, Professor Johnson announced the formation of the Institute and it opened the next year.

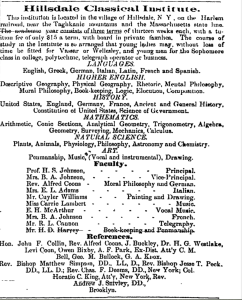

Advertisements appearing in the Hillsdale Herald show that the Hillsdale Classical Institute had a rigorous curriculum, offering classes in subjects including math, science, history and six foreign languages. Tuition was $15 per term. Lodging in private homes was available to students for $3 per week. The Institute’s goal was to prepare young ladies to attend Vassar or Wellesley, and equip young men to enter college at the sophomore level.

Among the prominent Hillsdale names listed in the ad’s “References” are Hon. John P. Collin, Dr. H.G. Westlake, Levi Coon, Owen Bixby, Ex-Dist. Att’y C.M. Bell, and George M. Bullock.

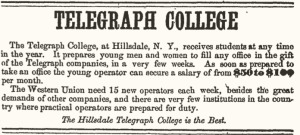

The institute also had a vocational course of study: telegraphy. This occupation, considered suitable for both boys and girls, was still a growth industry in the early 1880s. Prospective students were invited to learn to “read by sound.” Instruction was provided by Mr. R. L. Cannon, who in 1885, created a standalone entity called “Hillsdale Telegraph College.” (Diligent readers of the Hillsdale Historians may recall that Richard Cannon was the station manager of the New York and Harlem Railroad depot in Hillsdale and was the first person in town to have a telephone installed in his home in 1880. Read more here.)

In the closing years of the 19th century, the growth of publicly financed secondary schools led to a sharp decline in private academy enrollment and most of them closed in the early years of the 20th century.

But let’s get back to Professor Johnson. Herman Sidney Johnson was born on May 16, 1846 in Delaware, Ohio. His father, also Herman, had been president of Dickenson College (Carlisle, PA), which no doubt influenced young Herman to enroll there in 1863. He earned his Bachelor’s degree in 1867 and his Master’s in 1870. In the late 1870s, after teaching in Maryland for several years, Herman moved to Hillsdale to work as the editor of the Hillsdale Herald. The owner/publisher Ezra Johnson (E.J.). Beardsley also owned the Philmont Sentinel and maintained a printing press at the office of the Sentinel. (It is not clear if there was a “Johnson Family” connection between the two men, though that might explain Herman’s move to Hillsdale.)

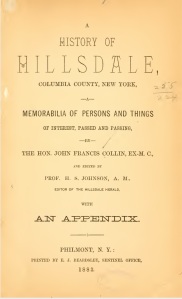

In 1883, Captain John Collin of Hillsdale (noted above as a reference for the Hillsdale Classical Institute) completed his definitive History of Hillsdale. It was edited by “Prof. H. S. Johnson” and printed in the Sentinel office by “E. J. Beardsley.”

(That suggests that at least for some period of time, Herman was serving as both the editor of the Herald and the principal of the Institute, perhaps accounting for the plethora of Herald news articles mentioning the Institute. We’d bet the ad space was cheap, too.)

Our research suggests that the Hillsdale Herald ceased publication in 1887, the same year that Henry D. Harvey, a local jewelry store owner, launched the Hillsdale Harbinger. Could it be that Mr. Harvey bought the Herald from Ezra Beardsley and re-branded it? (Beardsley continued to publish the Philmont Sentinel until his death in 1919; the paper ended publication in 1921.)

Our research suggests that the Hillsdale Herald ceased publication in 1887, the same year that Henry D. Harvey, a local jewelry store owner, launched the Hillsdale Harbinger. Could it be that Mr. Harvey bought the Herald from Ezra Beardsley and re-branded it? (Beardsley continued to publish the Philmont Sentinel until his death in 1919; the paper ended publication in 1921.)

The Institute was advertised as “in the village of Hillsdale,” though we haven’t been able to identify its location. But thanks to an 1886 Sanborn Fire Insurance map of Hillsdale we know the location of the Hillsdale Herald Printing Office, in the structure just east of Dimmick’s store (today’s Hillsdale General Store). It now houses the Gardner Insurance Company.

In any case, in 1883 Herman Johnson’s Hillsdale Classical Institute was doing well enough, with some 50 students, that Herman embarked on a side hustle.

In the February 25, 1884 edition of the Hudson Daily Evening Register, there was a news item which read in its entirety, “New York, February 25 – Mrs. Mary Stautz jumped out of a window yesterday and died from her injuries. She was insane.”

Right next to that was an article that the Register duly noted it had “clipped” from the New Haven Morning News.

“For some days, the following advertisement has appeared in the New Haven daily papers:

Single ladies and gentlemen who are desirous of forming each other’s acquaintance through corresponding will find it to their advantage to forward their address to (a blank representing a PO Box in New Haven.)

The article continued: “Professor Herman S. Johnson, the organizer of the Hillsdale Classical Institute, is a fair-haired little gentleman, about 43 years of age, whose blond mustache is about as heavy as that of a lad of sixteen. He is a professor of Greek, is a gentleman of varied accomplishments, excellent reputation and a member of a family of high social standing. He is a married man. The ‘professor’ is the prime mover in a matrimonial scheme whereby on a capital of $20,000 he claims a profit of $155,000 could be realized.”

The article quotes the professor stating that he was moved to enter upon this scheme mainly by a desire to happily unite in marriage couples who without his aid would be destined to become “old maids and wretched bachelors.”

Johnson’s big idea was to identify down-on-their-heels European nobility and put them together with young gentlemen and ladies of a type:

“As many families in America have in the past 30 years attained great wealth, it has become a society rage among these classes to seek matrimonial alliances with foreign nobility,” said Johnson. “We have evolved a plan whereby numbers of gentlemen in England and on the Continent, whose titles of nobility are genuine, shall become members of our bureau, and with whom alliances can be secured by ambitious American ladies.”

Johnson then explains his fee structure ($1 to apply, 50 cents per letter sent or received) and noted that should a marriage result, he would collect a sum equal to 1% of the lady’s property.

Johnson then explains his fee structure ($1 to apply, 50 cents per letter sent or received) and noted that should a marriage result, he would collect a sum equal to 1% of the lady’s property.

No doubt Johnson had been encouraged by the spate of Gilded Age marriages arranged by the ambitious wives of newly-minted millionaires. One such was Alva Vanderbilt, wife of second-generation railroad magnet William Kissam Vanderbilt, who engineered a match between her teenage daughter, Consuelo Vanderbilt, and Charles Spencer-Churchill, 9th Duke of Marlborough. The heavily indebted duke received an impressive dowry from the Vanderbilts, and when we say “impressive” consider this: There was an upfront payment in cash and stock in the family railroad worth $2,500,000 in 1895 — $75,000,000 in 2020 dollars — and $100,000 per year for life, $3,000,000 per year in 2020 dollars. In return, the Vanderbilts’ connection to British royalty immeasurably elevated their status in New York high society.

We have found no evidence that Herman’s stud farm for slightly shabby European nobility was successful. In fact, after the article about it appeared in 1884, Herman disappeared, only to show up in the 1910 federal census working as a public school teacher in Manhattan. But we’ll probably never know how he got there and what finally became of the man who helped pave the way for online dating and swiping right.

All images are courtesy of Hillsdale’s Historians Chris Atkins and Lauren Letellier

Follow the Hillsdale Historians and see their latest blog posts as well as past stories by signing up here