Our Environment, Animal Tips & the Great Outdoors

The Birth of the National Park System

George Catlin hated the law. He was seventeen years old when his father sent him to study at the Litchfield Law School. The elder Catlin was born in Litchfield County but after he completed his legal studies under Judge Tapping Reeve, he moved to the fledgling community of Wilkes-Barre, PA. There, young George Catlin met trappers, hunters, and families moving west. As a law student, he likely daydreamed about the frontier as Reeve and his partner James Gould lectured about torts and contracts. Catlin passed the bar and practiced law in Pennsylvania for two years. That was enough to confirm his thoughts about his profession, and Catlin quit his practice to study art.

Introduced to a group of Native Americans in Philadelphia, Catlin determined to capture a record of Native American life on canvas. He spent six years traveling among the various tribes of the Great Plains, ultimately completing more than 500 paintings. He hoped to sell these paintings to the government, believing that a governmental display would preserve for posterity a way of life Catlin could see was coming to an end. While he failed in this venture, he succeeded in selling the government on another vision, one that would, in time, come to be called “the best idea America ever had.”

… a nation’s park, containing man and beast

Traveling through the Dakota Territory in 1832, Catlin was concerned about the impact that westward expansion was having, not just on Native Americans but on the flora, fauna, and landscape of the West. Like many of that era, Catlin believed it was the wilderness that made America unique and which prevented the young nation from succumbing to the corruption that had become the hallmark of European nations. Yet that which made Americans exceptional was, in Catlin’s opinion, being threatened by his fellow countrymen. In his narrative of his travels among the Native American tribes, Catlin made a plea for the preservation not just of their lifeways, but of America’s natural beauty, dreaming that there might be “by some great protecting policy of the government preserved…in a magnificent park… a nation’s park, containing man and beast, in all wildness and freshness of their nature’s beauty!”

Traveling through the Dakota Territory in 1832, Catlin was concerned about the impact that westward expansion was having, not just on Native Americans but on the flora, fauna, and landscape of the West. Like many of that era, Catlin believed it was the wilderness that made America unique and which prevented the young nation from succumbing to the corruption that had become the hallmark of European nations. Yet that which made Americans exceptional was, in Catlin’s opinion, being threatened by his fellow countrymen. In his narrative of his travels among the Native American tribes, Catlin made a plea for the preservation not just of their lifeways, but of America’s natural beauty, dreaming that there might be “by some great protecting policy of the government preserved…in a magnificent park… a nation’s park, containing man and beast, in all wildness and freshness of their nature’s beauty!”

In making this first call for what is today the National Park Service, Catlin proposed an entirely new definition of the word “park.” At the time, a “park” was a “garden,” a manicured, orderly plot of land. The hedges were trimmed and flowers were grown in predetermined spots to enhance their aesthetic appeal. Even the undergrowth of forests was removed and moss planted as a natural carpet, to be swept as regularly as the floor coverings in a house. Catlin proposed something different, preserving nature as it was, not as humans thought it should be.

Catlin’s writings coincided with similar philosophical statements from other writers and artists. For example, in 1836, Ralph Waldo Emerson published his essay Nature, which argued that God’s greatness was inherent in man’s natural surroundings. That same year, Thomas Cole, painter and leader of the Hudson River School, unveiled his masterpiece The Oxbow, which suggested that man and nature could live in balance, but cautioned against disturbing this balance.

Businessmen were soon profiting from Americans’ newfound appreciation of nature. Peter Schutt purchased a large tract of land in the Catskill Mountains that included Kaaterskill Falls. There he built not only a hotel but a dam that prevented water from spilling over the falls. Only when guests paid the required fee would Schutt open the dam, “turning on” the waterfall. If Schutt was merely cashing in on nature, his actions inspired others in their belief that nature needed to be preserved, not just enjoyed. In the 1850s, Henry David Thoreau declared that “In Wildness is the preservation of the world” in his essay Walking, and highlighted the irony of what most deemed “progress” in his writings about the expansion of rail lines in Walden.

That so-called progress was devastating the environment in areas across the country. Northwestern Connecticut was denuded of trees in order to make charcoal for the iron industry. Lumbering, tanning, charcoaling and the paper industry threatened the Adirondacks. Most of Michigan was deforested in a twenty-year period for the lumber industry as well as by those clearing farm plots made available under the 1862 Homestead Act. Perhaps no part of the country faced the environmental devastation as severe as that brought about by the 1849 Gold Rush in California. Water power was harnessed to bring down mountains, and the sediment released by this process clogged streams and rivers. Forests were cleared and chemicals polluted the soil. The ramifications of these environmental calamities extended to the nation’s cities, whose supplies of drinking water, food, and firewood were suddently threatened.

Forever wild

Given the magnitude of man’s impact on the environment in California, it is no surprise that it was there that the dream of national parks first became reality. In 1862, California senator John Conness and steamship captain Israel Ward Raymond sought to protect the majestic sequoias and the breathtaking valley of Yosemite from development, instead setting it aside for the enjoyment of the people of the state. In 1864, Abraham Lincoln signed into law a bill turning over this land – which had been owned by the federal government – to the State of California as the nation’s first state park. Other states followed suit. New York, for example, created a state park at Niagara Falls and, in 1895, set aside the Adirondack Park as an area to be “forever wild.”

This model may have continued to be used in place of creating national parks had some of the most spectacular landscapes in the country not been in federal territories. As early as the Lewis and Clark expedition of 1804 to 1806, reports of an otherworldly environment in the basin of the Yellowstone River of Wyoming drew the curious to explore the region. Scientific explorations to the region in the 1860s and early 1870s – and especially the works of the painter Thomas Moran and photographer William Henry Jackson, both of whom accompanied the 1871 Hayden Geological Survey – so enthralled the nation that railroads soon began running special routes to Yellowstone. Development of this sort placed the fragile environment at risk, and Congress – whose collective imagination had also been captured by the artists – took the unprecedented step of conserving two million acres with the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act, signed by President Ulysses S. Grant on March 1, 1872.

It would be another eighteen years before a second national park was created. While the creation of Yosemite as a state park was a landmark event in the conservation movement, it proved to be less effective at protecting the land than was hoped. John Muir, the Scottish-born naturalist who had become the leading advocate for Yosemite and the High Sierra, had grown increasingly concerned about overgrazing and logging of sequoias within the state park and lobbied Congress to transfer the lands to the custody of the federal government. Yosemite National Park was created on October 1, 1890; this was actually six days after Sequoia National Park was established, also to protect the massive trees from logging.

Nine years later, the creation of Mount Rainier National Park exposed a rift in the nation’s burgeoning community of environmentalists. Some, like Gifford Pinchot (a long-time advisor to Theodore Roosevelt), wanted land set aside to ensure that its natural resources would remain available for use by future generations. Cutting down trees for lumber was acceptable so long as it was done in a sustainable way. Others, like Muir and the nascent Sierra Club, were more preservationists than conservationists. Muir had visited Mount Rainier in 1888 and returned convinced that its status as part of the Pacific Forest Reserve did not give it adequate protection. He lobbied Congress for the better part of the 1890s to create the Mount Rainier National Park, which was established in 1899, only after Congress was assured that the land was suitable for neither farming nor mining, and that the creation of the park would require no new federal appropriations.

The Roosevelt impact

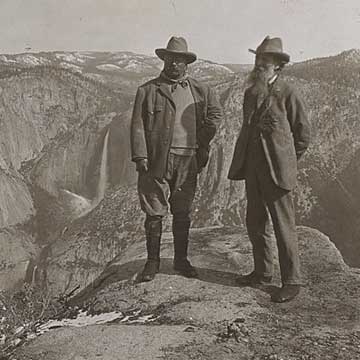

The ascent of Theodore Roosevelt to the presidency two years later dramatically changed the trajectory of the establishment of national parks. Both a legendary hunter and the founder of the environmentalist Boone and Crockett Club, Roosevelt wielded a strong belief in both the conservation movement and the power of the federal government. Roosevelt’s approach to the protection of land, flora and fauna is perhaps best exemplified by his 1903 visit to Pelican Island, FL. Concerned that the development of a hotel would destroy fragile bird habitats, Roosevelt – a noted ornithologist – asked Attorney General Philander Knox, “Is there any law that will prevent me from declaring Pelican Island a Federal Bird Reservation?” When Knox replied in the negative, Roosevelt spouted, “Very well then, I so declare it.”

National parks can only be created by acts of Congress, and only four were established during Roosevelt’s presidency: Crater Lake, Wind Cave, Mesa Verde, and Glacier. However, through his advocacy for the Antiquities Act, passed by Congress in 1906 as well as prior legislation that allowed for the establishment of national forests and wildlife refuges, Roosevelt reshaped the relationship between the federal government and the American landscape. In seven and a half years as president, Roosevelt designated 150 national forests, 51 bird sanctuaries, four national game preserves, and 18 national monuments. These, combined with the national parks created by Congress during his presidency, set aside over 230 million acres of land. Conservationists and preservationists may have argued about the details, but both factions celebrated Roosevelt’s vision. Farmers, ranchers, and miners, however, immediately erupted against what they saw as a broad overreach by the federal government.

When Woodrow Wilson designated seven national monuments and signed the legislation providing for an additional seven new national parks, it was clear that the government needed to play a more active role in the supervision of these lands. Prior to 1916, each national park, monument, forest or bird sanctuary was independently operated under the auspices of the Department of the Interior.

Yellowstone, besieged by poachers and ravaged by souvenir hunters, turned to the military for help, with the army patrolling the park for decades. Ultimately, on August 25, 1916, Wilson signed the National Park Service Organic Act, establishing the National Park Service to administer these lands. In addition to creating the organization, the act gave the National Park Service its mission: “to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and wildlife therein, and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

Today, the National Park Service administers 423 units – including 61 National Parks – spread across all fifty states and several territories. More than 325 million Americans visited a National Park System site in 2019. This staggering number suggests that these parks remain one of America’s best ideas and also forces us to ponder the question of what would have happened to the land had George Catlin been a little more fond of the law.

To learn more visit www.nps.gov.